At Newman College on 16 October 2012, Val Noone gave the following talk on his field trip in July this year to the sites of the Murray Valley labour cooperatives which Irish revolutionary Michael Davitt visited in 1895.

For the third time in a decade I have learned much about the 1890s in Australian history, and not just Irish Australian history, by researching and writing about Michael Davitt’s 1895 visit to Australia. The key source for this is his 1898 book, Life and Progress in Australasia, an important, elegant and somewhat rosy but nevertheless neglected source.

This my third paper about Davitt concerns the spotlight he put on cooperative and socialistic settlements in the Murray Valley of the 1890s, which are hardly ever mentioned these days but deserve a mention in this United Nations Year of the Co-operative. By way of exception to the general trend, Verity Burgmann’s “In Our Time”: Socialism and the Rise of Labor, 1885-1905 drew on, and supplements, Davitt’s book in her insightful summary of the Murray Valley cooperative settlements.

From 1893, in a time of high unemployment the South Australian government, pressured by the trade union movement, financed pioneer cooperative farming settlements along the Murray between Morgan and Renmark. Under the legislation “any twenty or more persons of the age of eighteen years and upwards may, by subscribing their names in the manner prescribed, form an association for the purpose of Village Settlement”. A grant of 16,000 acres was made to any group of 100 families that applied. The government gave loans for supplies and equipment to 50% of the value of improvements made, with a three-year interest-free period and then ten years at 5%. This was a vision of a new cooperative and anti-capitalist way of doing things.

Davitt saw a moment of hope and possibilities. His account raised the questions of what sort of social order prevailed in Australia during the fateful 1890s and what sort of society Australia might have become.

Tonight’s paper raises again, as labour and other historians have done in recent decades, the topic of whether the Australian labour activists of bygone years were, like their bosses, often blind to Indigenous rights and environmental degradation, or not, and why or why not. In my conclusion I shall relate Davitt’s trip and my field trip to these matters.

With Keith Pescod who wrote recently in the Australasian Journal of Irish Studies about trade unions I am trying also to take a small step towards overcoming the startling lack of a substantial study of the Irish in the Australian labour movement.

Sketch of Davitt’s 1895 trip

At midday on Friday 14 June 1895, a winter’s day in Adelaide, mild by comparison with winter in England and Ireland where he came from, Michael Davitt boarded a steam train for Morgan on the banks of the Murray River, 100 miles (165 kilometres) to the northeast. Member of the British parliament, leader of the international labour movement, veteran Irish revolutionary with more than seven years jail served in the cause of his native land, Davitt was a high-profile visitor. He had just completed the first of seven months he was spending touring Australia and New Zealand.

As Carla King outlined here at Newman College in her 17 July 2012 lecture on the places, personalities and issues of Davitt’s visit to Australia, Davitt had at least four objectives: to speak in a general way on Irish matters; to see Australia and how things worked in what seemed to him a flourishing new society; to benefit his health; and, by lecturing, to make a little money for the Irish Parliamentary Party at home and to defray his expenses.

This Friday in June he was tackling one of the most important objectives within his plan to learn about Australia, namely, to study the new socialistic cooperative colonies along the Murray River between Morgan and Renmark. He was delighted to have as his travelling companion for the first two days John Anderson Hartley, inspector general of schools in South Australia, a leading progressive figure in education who as a Wesleyan Methodist favoured inclusion of Christian education in state schools.

Davitt, who was to use the concept of “progress” as an organising theme for his 470-page 1898 book about this trip, found many interests in common with Hartley and learned much from him. Ironically for those dedicated to progress, Hartley aged 54 died the following year while riding his newly acquired bicycle as a result of a collision with a horse ridden by a butcher’s boy.

After Davitt and Hartley’s train reached Morgan at 6.00 pm, they enjoyed a hearty tea at Lamberts Hotel before taking the 8.30 pm coach for the demanding overnight trip along 70 miles (115 kilometres) of rough tracks to Renmark. Unhappy about the “foolish enterprise” of this ride, they were pleased to see sunrise over the Murray River, and were relieved to reach Renmark at 9.30 am and have breakfast at Meissner’s Hotel.

Renmark, then six years old, was the centre of an innovative irrigation scheme run by the American Chaffey Brothers, William and George. Hundreds of people in the town were newly arrived from the United Kingdom to join the project. The Chaffeys had gone broke, owed wages and bank loans, and the South Australian government had taken over the finance for the scheme.

Be that as it may, as the Renmark Pioneer reported the next morning, the Saturday, Davitt was driven round the settlement, in a four-horse drag, accompanied by the youngest brother Charles Chaffey and some colleagues. Charles had been left in charge at Renmark while the two older brothers were away fighting legal battles over their debts or starting new schemes. The local paper reported that Davitt “highly commended the enterprise of the promoters and the settlers in turning a Mallee wilderness into a fruitful garden”.

Citizens of Renmark asked Davitt would he give one of his “eloquent and interesting lectures, especially as the [unnamed] dramatic performance had been postponed, the packing shed being fitted up ready for the occasion”. Unfortunately for the Renmark people, Davitt and Hartley “set off down stream immediately after lunch, intending to visit Lyrup and some of the other village settlements above Morgan, a vehicle and horses for their conveyance having been provided by Messrs Chaffey Bros Ltd.”

Saturday afternoon Davitt travelled 30 miles (50 kilometres) to Lyrup in time for a meeting with the community there, stayed the night and some of the next day. Sunday evening at sunset he arrived at the next colony along the river, namely Pyap. Monday was spent at Pyap and in brief visits to New Residence (7 miles on) and Moorook (another 5 miles), ending the day at the Kingston settlement (again 5 miles) where Davitt slept in a tent.

Indeed, as happens when trying to fit several visits into a busy timetable, by turning downstream Davitt thus dropped from his itinerary a visit to the already much publicised cooperative colony at Murtho, which he had hoped to visit. As we will see he nonetheless included in his book some of what he had learned about Murtho. Below I will discuss in detail his views on the cooperatives.

Tuesday he left Kingston at 11.00 am for Overland Point, walking the 7 miles (12 kilometres) in three hours. A coach took him next morning to catch the 8.00 am train to Adelaide. He had limited his visit to five days so as to fit in a lecture at Peteresburg (since World War I Peterborough) on Thursday 20 June.

The above sketch of Davit’s visit is based on the forty pages he included in his 1898 book, his diary in Trinity College Dublin, and the local newspaper, Renmark Pioneer. And my ability to make sense of his itinerary has been much enhanced by following his steps, well more or less, on a recent field trip.

Outline of our 2012 trip

On Monday 2 July 2012, Carla King, Mary Doyle and I set out at 5.00 am from Melbourne and drove to Renmark to spend three days retracing Davitt’s steps around the cooperative settlements of Lyrup, Pyap, New Residence, Moorook and Kingston. As far as we know there is no account of anyone having done so previously. My thanks to Carla and Mary who contributed much to this paper but the mistakes are mine. Carla has generously shared her transcripts from Davitt’s Australian diaries. I also want to thank Julie Kimber, Phillip Deery and Frank Bongiorno for help with references.

Carla, who has already published several works about Michael Davitt and has edited many of his writings, is working on a biography of Davitt. Moreover, she was in Australia in 2012 as the recipient of a Nicholas O’Donnell fellowship from Newman College and the Gerry Higgins Chair of Irish Studies in order to work on the 1895 Davitt visit to Australia.

When we stopped for breakfast at Charlton, the waitress showed us the mark on the leg of the table recording the height of the water running through the café during the record floods of January 2011.

Over a cup of tea at his home of the family farm at Nullawil, Ted Ryan, occasional participant in these seminars, explained, among other things, some recent work he and his colleagues have been doing on the history of Aboriginal languages in the Mallee. A visit to the Hatta Lakes and by 4.00 pm we were talking with Stella at the Renmark Irrigation Trust – at the old Chaffey HQ – about available historical resources.

For us and our contemporaries the Murray-Darling Basin is at risk as competing upstream users battle against South Australian users and many people looking at the river red gums and Coorong wonder if, even after two years of good rain, the river is about to die.

We come into this so called Riverland region knowing that for perhaps 40,000 years, from its junction with the Murrumbidgee down to the Coorong, the Murray Valley has been the most densely settled area of Aboriginal Australia.

At the Comfort Inn Citrus Valley Motel where we stayed, we had the good fortune of meeting manager, Robert Wood, who had formerly worked in the local council and who put is in touch with some local historians. We enjoyed an evening meal at the RSL Club overlooking the Murray, thinking but not comprehending all that has happened along the river since the days when Naralte people fished and hunted here.

Tuesday, thanks to the Renmark Irrigation Trusts, the three of us spent several hours studying the hand-written originals of the 1896-1898 notebooks of Samuel McIntosh, government commissioner for supervision of village settlements, containing his assessments of their progress and recommendations for improvement, or in some cases closure.

At the Renmark library Maxine Hodgson and Di Decol introduced us to their superb local history collection, where we spent a couple of hours on some good books on the village settlements by David Mack (particularly helpful), Alan Jones, Jean Nunn, Pat and Brian Glenie and Richard Vynne Woods, as well as a relevant history of irrigation by Hallows Thompson and Lucas.

We visited Olivewood, a onetime Chaffey home, where Colin Cubank was a courteous and informative guide. We then investigated the site of Lyrup, the first of the settlements which Davitt visited. Thanks to Robert from the motel, we also met up with Neville Nattrass, almond farmer and local councillor, who explained a little of the history and a lot about present economic and environmental pressures on the small farmer, especially competition from multinational agribusinesses planting thousands of acres of almonds.

The next day we began early with an meeting with Heather Everingham, a knowledgeable and industrious local historian, who graciously shared her expert knowledge and discussed our queries. We also enjoyed a tour of the lively Goanna Gallery run by her artist husband Steve. Heather subsequently wrote a feature for Murray Pioneer about Davitt’s 1895 visit, and she included an item about our field trip.

Most of the day was spent walking the ground of the other settlements Davitt visited: Pyap, New Residence, Moorook and Kingston. On our way back to Renmark we had a profitable visit to the Central Irrigation Trust where the CEO Gavin McMahon and his staff made us most welcome. In particular they briefed us on some twentieth century history of the settlements. There, as in my telephone dealings with Geoff Parrish of Semaphore, a retired irrigation officer, we are in debt to Phillip Moore for background briefings and for introductions to key people. Thursday we returned to Melbourne, checking out as we went a new brand of vanilla slices in Ouyen and greeting the emus at Mount Wycheproof reserve.

Five cooperatives visited by Davitt

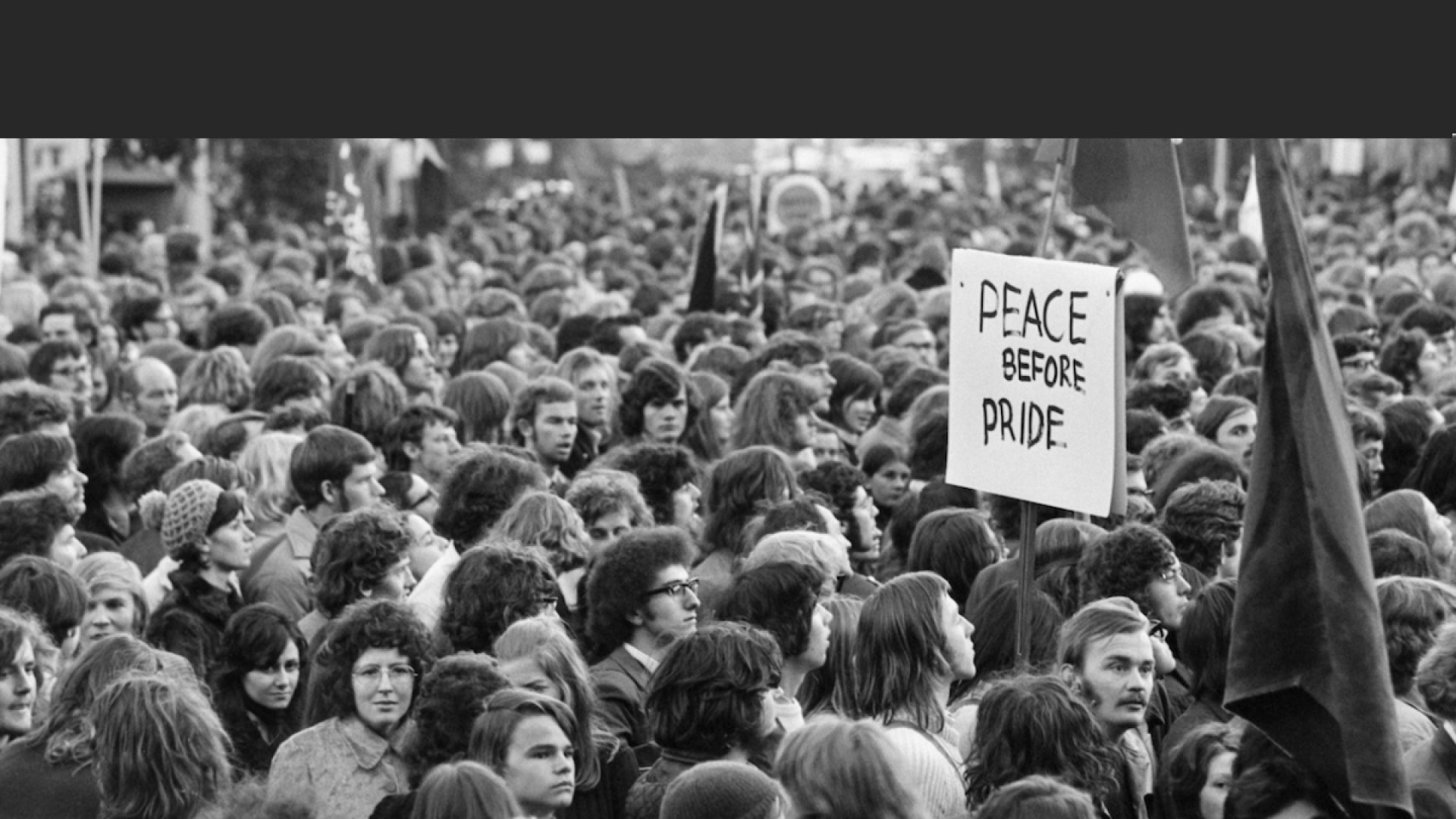

Here then is an introductory tour of the five cooperative settlements visited by Davitt, illustrated with images taken by Davitt’s contemporaries as well as with images taken on our field trip. Davitt was a keen photographer but no photographs of the settlements survive in his collection.

a. Lyrup: Irish trade unionist link, baker his host

Of Lyrup, Davitt wrote: “I confess I found the experience one of the most agreeable of many pleasant and instructive incidents in my tour through Australasia.” Davitt found common ground with the “semi-communistic” ways of this settlement, its doing away with money and so on. He admired Rupert Bambrick, the early organiser of this group, stayed with Cornelius Egan, a baker, and developed a close link with Irish-born Mr Shelly, founder of the Cordial Makers Union in Adelaide, leader of the Adelaide Trades Council and an active member of the Hibernian Society. Here are images of the Lyrup camp, its mill, some vines and a pump with flumes.

b. Pyap: statesmen and bush lawyers

Davitt left Pyap unhappy about their preference for excessive oratory and debate ahead of work, and for recognising women’s right to vote but then letting it lapse. He called this “The statesmen’s camp”. It consisted of 90 carefully chosen mechanics and their families. Better to have a mix of skilled and unskilled people, Davitt commented. Technically, Pyap is remembered for a long chimney-tunnel from the wood-burning steam pump reaching to the top of a hill, in order to give the fire the best possible draught. Wikipedia says that Roscrea-born Daisy Bates lived at Pyap for several years from 1936.

c. New Residence, Moorook and Kingston

The next settlement which Davitt visited was New Residence, already in trouble and, by the time he wrote his book, closed. Nonetheless, he described its chairman Harry Hoffman as a Hercules.

Good storyteller that he is, Davitt gives plenty of space to the Cornish fisherman whom he met along the road who was individualist and strongly opposed to those who held things in common. Also he asked the Cornishman to tell a contact named Mr Conneybeare that his friend Charles Thomas had been killed in an accident at Southern Cross, Coolgardie, in Western Australia. At Moorook and Kingston he met dock workers and their families from Port Adelaide who had been neighbours and comrades in the trade union movement before moving to the Murray. They had not moved so much in desperation in the face of unemployment and poverty but rather as workers who wished to experiment with a new socialist social order. Davitt was delighted to meet at Kingston a communist midwife from Cork who told him, among other things, that she had never been so busy and never so happy.

d. Murtho: single taxers and Christian socialists

From my limited bibliographical searches, the settlement at Murtho, upstream from Renmark, has had most written about it, partly because its members atypically came from, or were connected with, intellectual and literary backgrounds. Davitt noted that according to reports he had they were followers of Henry George and his single tax policy. A key leader there was John Birks, a pharmacist and Methodist. This group brought personal financial capital with them and saw their ethical Christian socialism as an alternative to class struggle. They had links to Methodist Rev Hugh Gilmour of Wellington Square and the Adelaide journal The Voice. They read Thoreau, Ruskin and Carlysle. Historian Melissa Bellanta has pointed recently to a form of mateship at Murtho which included feminism. Their motto was the well known, “From each according to their ability, to each according to their need”.

e. “A big experiment”

Davitt saw the cooperative settlements as an important “big experiment”. Around Australia in the winter of 1893, a harsh one in Adelaide, some 25% of tradesmen were unemployed and the rate was higher for unskilled workers. Davitt was impressed by the role of trade unions in promoting the scheme and the Kingston government for responding. In his book he included three pages of statistics and other documentation. Davitt was impressed that the settlements – often living in humpies because they gave priority over house building to clearing the land – grew wheat, barley, lucerne, vegetables, vines and citrus while keeping cattle, horses, pigs and sheep. In places he writes as if life on the land was inherently healtheir and more moral than life in the cities. At one time he summed up his feelings:

My earnest wishes while I was among the villages on the Murray were for the triumph of the co-cooperative-communistic plan at the end of the experimental period. Everything I saw contrasted most favourably with the ordinary conditions of wage-earning life, in even the highest-paid labour centres of Australia. There was no poverty or want felt by anybody. The work, though necessarily rough in the main, was not exhausting, while it was robbed of that which links the task of ordinary daily toil to servitudes – the feeling that you were at the disposal of somebody for so much.

Discussion of findings

a. Comparison with Leongatha

By way of comparison with what Davitt found in South Australia I revisited John Murphy’s booklet on the Leongatha Labour Colony of 1893-1919 which catered for over 9000 men. For a number of years an Irishman, Jacob Goldstein, was in charge of the Leongatha colony. Born in Ireland of Polish Jewish and Irish background, he has another claim to fame, namely that he was the father of well known suffragist and anti-war resister Vida Goldstein.

I also investigated other sources on related settlements in Victoria and was amazed to find how big the village settlement movement of the 1890s was in Victoria.

The village settlement movement had both a socialist wing who wanted an alternative society and also a mainstream capitalist wing. The latter, who saw it as a way of getting menacing unemployed workers and agitators out of the cities, tended to use the settlements to provide a pool of cheap casual farm labour. In contrast to Murphy’s positive account, R E W Kennedy has argued that those controlling the Leongatha Labour Colony belonged in “the anti-utopian tradition of the workhouse labour-test” who were fearful of “socialist claims of a right to work guaranteed and, if necessary, implemented by the state”.

Nonetheless Burgmann, who shares the instinct of Davitt, Kennedy and others, quoted L K Kerr in defence of the labour colonies:

At the very worst, [the labour colony movement] provided an estimated 22,270 Australian with food and shelter in a period of great national distress. It saved good, hard-working citizens from starvation and gave their children the chance of a better life. It delivered them from insanitary slums to the healthy bush life. Finally, communalism gave most of its adherents an independence and resourcefulness which they could never have experienced if they had remained in the cities.

b. Links to New Australia in Paraguay

Many of those who joined the cooperative labour colonies had considered going with William Lane – he the son of an Irish father – to his utopian New Australia and Cosme colonies in Paraguay. When Lane’s chosen ship the Royal Tar spent two days in Adelaide in December 1893 5600 people visited it. Indeed, some in government supported the colonies in the Murray Valley to stop more people leaving Australia. A leading newspaper editor in the Renmark region, Harry Taylor, who supported local development and imperial policies, had begun his public career by joining William Lane in New Australia and then Cosme.

c. Work, water and progress on Aboriginal land

Elsewhere in his book Davitt speaks on support of the rights of Aboriginal people, but they are invisible in his accounts of the Murray colonies. I am not sure what to make of that. Like most of his contemporaries and like most of us in our youth, he took the concept of “progress” to be good and normal. In the past five decades as the public has seen more evidence of factors such as environmental degradation, high levels of carbon in the atmosphere, the exponential use of fossil fuels, climate change and global warming, that concept has become less simple.

Davitt, like most Australians, English and Irish of his time – and indeed as Dipesh Chakrabaty has recently argued like most twentieth-century leaders of newly emerging nations such as Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt, Soekarno of Indonesia, Jawarhal Nehru of India – saw the land as something to be used and brought into the capitalist (or socialist) economy, and assumed the appropriateness of an industrial economy based on carbon. He said of the Murray Valley:

Six years previously Renmark was part of the uncleared bush. Irrigation has produced the industrial miracle which is found there now. Without water the soil grows nothing but the everlasting gum, she-oak and Mallee scrub. How these trees manage to live in so dry a climate is one of the many wonders which the European learns from a visit to these anomalous antipodes.

He also said of the colonies overall:

The land is of excellent quality in itself. The work of irrigating it alongside the largest of Australian rivers was comparatively easy: fuel for the pumps being found in abundance round every village.

The wood and water of the Murray Valley were economic units to Davitt and his contemporaries. No thought then that the Murray-Darling Basin and its river red gums and its Coorong could ever be a dying ecosystem.

It is our duty to remark without accusation that Davitt’s writing lacks a sense of nature in its diversity and wildness as something that we respect rather than own. As Geoff Lacey has recently argued, one of the great tasks of our time is to find an ecological understanding built on our experience of the power and mystery of the landscape – an understanding that was, and is, part and parcel of the worldview of many Indigenous Australians – articulate it and make it work. Our study of Davitt on cooperatives is all the stronger for being seen in a perspective of today’s pressing new challenges.

d. Davitt and others on why the Murray coops closed

Except for Lyrup, which continues in a limited way to be a community to this day, within a decade the Murray River labour colonies closed. Writing two years after his visit Davitt, well informed by mail and cable, saw that this might be the case. In his book he offered a brief explanation:

the desire to own property of some kind is all but impossible to eliminate from the minds of those who are bred and born under the property-owning system of our modern society.

Indeed, he was philosophical about it all, mentioning lessons from the seventeenth and eighteenth-century Jesuit redactions in Paraguay, Fabian and Marxist thought and the Cosme case.

The historian of Lyrup, Alan Jones, goes so far as to say that Lyrup only succeeded by moving away from socialism and communalism after Shelly and other committed socialists found themselves in a minority and resigned.

On the other hand there were concrete, physical and economic reasons for the closures. Syd Phillips, sometime teacher at Lyrup in its communal days, said that the pumps and engines sent by the government to the settlements were never new or efficient. Burgmann quotes him as saying that had the government sent a party of police to clear out the inhabitants, it would not have been more effective than “that rusty, ancient, misfit collection of wheels and cylinders”. Other authors point to seepage losses from unlined channels, subsequent land salination, unsuitable crops planted, lack of transport to markets, fruit diseases and many other troubles. In dry years the Murray would be dry in places, impassable even to small flat-bottomed boats.

e. Davitt and the cooperative ideal

In this the United Nations year of the cooperative, Davitt’s enthusiasm for the labour colonies experiment along the Murray in the 1890s keeps alive the ideal that it is possible to pursue economic progress while still respecting the needs of those less wealthy or less powerful. At a one-day conference on cooperatives at Melbourne Trades Hall last month, Stefan Gigacz quoted two contemporaries of Davitt from the English trade union movement, Tom Mann and Ben Tillett, as saying that the new unionism of the 1890s was about building “a co-operative commonwealth”. Coinciding with the UN promotion, Moira Scollay has published a detailed study of a twentieth-century grass roots cooperative in Melbourne’s northern working-class suburbs, which indeed was named after Peter Lalor, the Irish leader of the miners at Eureka. In such a context, Davitt’s efforts to draw attention to the Murray River labour colonies have contemporary relevance.