By Rowan Cahill

I never knew my grandfather, the father of my mother. But he was a WWI veteran. Originally a baker by trade in Beechworth (Victoria), by the First World War he was a horse whisperer in the Tumut region of NSW. At the age of 50 in 1915, he went to war with his horse Conquerer, with the 2nd Remount Unit.

This was a special unit of horse experts, recruited to train warhorses. It was dangerous work; the horses were drawn from across the British Empire, and the Remount task was to break and train them in Egypt. The horses they trained were used in the Sinai and Palestine campaigns.

This was a special unit of horse experts, recruited to train warhorses. It was dangerous work; the horses were drawn from across the British Empire, and the Remount task was to break and train them in Egypt. The horses they trained were used in the Sinai and Palestine campaigns.

The maximum age of enlistment for this unit was 50, the idea being that the old horse experts would do the horse training, leaving young men the task of battle on the front lines. The leader of my grandfather’s unit was poet, war correspondent, and horse expert, ‘Banjo’ Paterson.

Paterson recorded the names his outfit were variously given by observers and members: the ‘Methusaliers’, the ‘Horsehold Cavalry’, the ‘Horse-dung Hussars’.

A year later Trooper Dalton was back home, the work of his unit done and subsequently disbanded. He came home with head injuries as the result of his work with the horses. Waiting for him on Tumut railway station was his youngest daughter, 11 years old, my future Mum; years later in her dotage she cried as I held her ancient hands as she remembered that day and that Conquerer, the horse he had taken with him to Egypt, had been left behind.

When Trooper Dalton sought an incapacity pension for his injuries, his application was rejected. His service dossier records the reason in clear bold bureaucratic penmanship; simply, he was ineligible because his injuries were not sustained in battle.

So he and his wife and three daughters ended up in the Milperra Soldier Settlement scheme on the outskirts of Sydney, trying to reinvent himself as a poultry farmer, part of nervous officialdom’s plan to deal with large numbers of demobbed service personnel, unemployment, and thwart the possible allures of crime and political militancy. The streets of the settlement were named after the battlefields many of the settlers might rather forget.

Farming was an endeavour Trooper Dalton and most of his Milperra comrades failed at, the promise of rural productivity and cash crops largely illusionary, not helped by the prerequisite for entering the settlement being some form of injury/incapacitation. Trooper Dalton did not warrant a pension, but did warrant ‘poultry farming’.

The settlers dealt with officious bureaucrats who monitored their progress and chased up overdue repayments for the settler-blocks, and with promised infrastructures that largely remained ‘promised’. By 1923, only 18 of the 56 farms were occupied, and private enterprise moved in to create future suburbia.

A failure at poultry farming, Trooper Dalton reinvented himself as a tram conductor on Sydney’s Dulwich Hill line. But it was not for long. The blackdog ![nla.pic-an23478290 Hurley, Frank, 1885-1962. [Horse-drawn Australian artillery silhouetted along the Poperinghe-Ypres Road, Flanders, 1917] [picture] : [Flanders, World War I] [between 1910 and 1962] 1 negative : glass ; half of full plate. Part of Hurley negative collection [picture] [1910-1962] Horses Hurley](https://i0.wp.com/labourhistorymelbourne.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/horses-hurley.jpg?resize=300%2C235&ssl=1) took possession of his senses and on 17 May 1919, he died in the soul destroying, overcrowded confines of the Rydalmere Psychiatric Hospital (NSW), one of the worst ‘lunatic asylums’ of the time, surrounded by its green/brown painted rooms, ever present dampness, and the smells of urine, faeces and unwashed bodies. As medical critics of the time pointed out, the facility was actually exacerbating mental illness.

took possession of his senses and on 17 May 1919, he died in the soul destroying, overcrowded confines of the Rydalmere Psychiatric Hospital (NSW), one of the worst ‘lunatic asylums’ of the time, surrounded by its green/brown painted rooms, ever present dampness, and the smells of urine, faeces and unwashed bodies. As medical critics of the time pointed out, the facility was actually exacerbating mental illness.

The causes of tram conductor Dalton’s death according to his Death Certificate were “acute mania” and “exhaustion”. Treatment of this at the time variously involved isolation, restraint, and sedation. But he died in uniform: the shapeless grey tweed clothing of the asylum’s uniform, cloth hat, heavy boots.

As a result of his death, Mum’s young life was irrevocably changed; she left school, entered the workforce and, in her early teens, headed for the city, boarding houses, training and secretarial work.

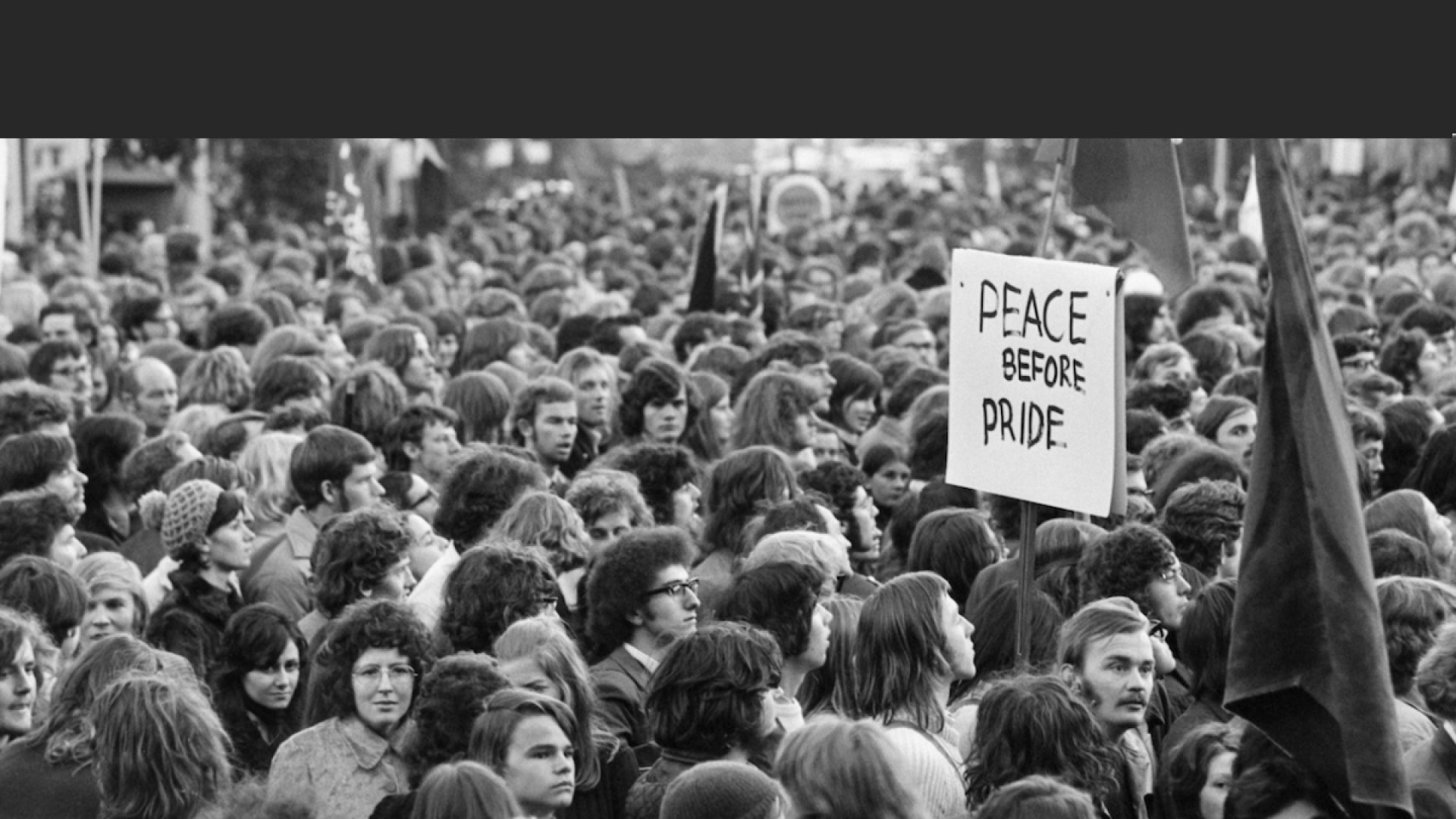

Unlike Dad who reckoned ‘military service would make a man’ of me, Mum was never a pro-war enthusiast or glorifier or Anzac Day rememberer. During the 1960s when I denied the state the right to conscript me and became a ‘conscientious objector’, she sat in the court which sought to compel me to ‘serve’ in another Australian feat of arms in the service of imperialism, to support me.

Thank you Mum, and Trooper Dalton who cast a long shadow.

Rowan Cahill was prominent in the anti-war, student, and New Left movements during the 1960s and early 1970s. He was also one of the founders of the Free University. Rowan has worked as a teacher, freelance writer, agricultural labourer, and for the trade union movement as a journalist, historian, and rank and file activist. Currently a part-time teaching academic at the University of Wollongong, and an Honorary Fellow with the university’s Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts, he has published extensively in labour movement, radical, and academic publications. His books include The Seamen’s Union of Australia, 1872-1972: A History (with Brian Fitzpatrick, 1981), Twentieth Century Australia: Conflict and Consensus (with David Stewart, 1987), A Turbulent Decade: Social Protest Movements and the Labour Movement, 1965-1975 (edited with Beverley Symons, 2005). For a more detailed listing of Rowan’s writings, click here. He runs the Radical Sydney blog with Terry Irving and is a regular contributor to the Melbourne Branch’s newsletter Recorder.

A reflection on one life that reveals so much more about the real (and lasting) impacts of WWI than ninety-eight percent of the official “commemoration” activities. A war is something that never really has an “end”. The corrosive ripples of them continue to erode even far distant shores years and years later.