By Rowan Cahill*

William Horace (Bill) Langlois died in September 2015, aged 92. When I first met him, back in 1970, he was twenty-two years older than me, a time span that now, me writing at the age of 70, seems brief, but in the eyes and mind of the youth that was me back then, he seemed to belong to another world and time. As we both aged, him ahead of me, I came to think of him as the Ancient Mariner, the story-teller who delays and entrances the travelling wedding guest in Coleridge’s poem…

In 1970 I was a young leftist, radicalised by Conscription and the Vietnam War, a bona-fide Enemy of the State according to my now released ASIO file of the period, a recently minted BA (Hons), and engaged by the militant Seamen’s Union of Australia (SUA – now part of the Maritime Union of Australia) to complete a history of the union commenced earlier by the late Brian Fitzpatrick (1905-1965). And it was when I began my research that I met him – Bill Langlois, seaman and unionist.

Bill was born in North London in 1923, and started his career as a seaman at the age of 13, working in the coastal trade on the shallow draught Thames sailing barges. It was tough and demanding work, lowly paid, inescapably exposing crews to the weather, and attracted young boys desiring to go to sea, quickly dispelling many of the urge.

But Bill stayed the course, and early in his career recognised he was part of something more than a job, and that seafaring had its culture, traditions, and skills; he resolved “to be a good sailor”. Symbolic of his immersion in ‘seafaring’ was the encyclopaedic knowledge of knots he accumulated in his lifetime, and his skill in decorative rope weaving, transforming basic maritime essentials into pieces of art.

During World War II Bill remained in the merchant marine, and worked on at least three of the dangerous and deadly North Atlantic convoys, maybe four, shipping essential supplies from North America and the UK to the northern ports of the Soviet Union. These convoys were constantly under German air, surface, and submarine attack, and took place under severe weather conditions, with drift ice, fogs, and strong currents compounding difficulties. On one of his voyages his ship was torpedoed and he and fellow survivors spent six days in a lifeboat. In 1944 he was part of the merchant marine support that was essential to the success of the Normandy landings and the Allied invasion of Nazi Europe.

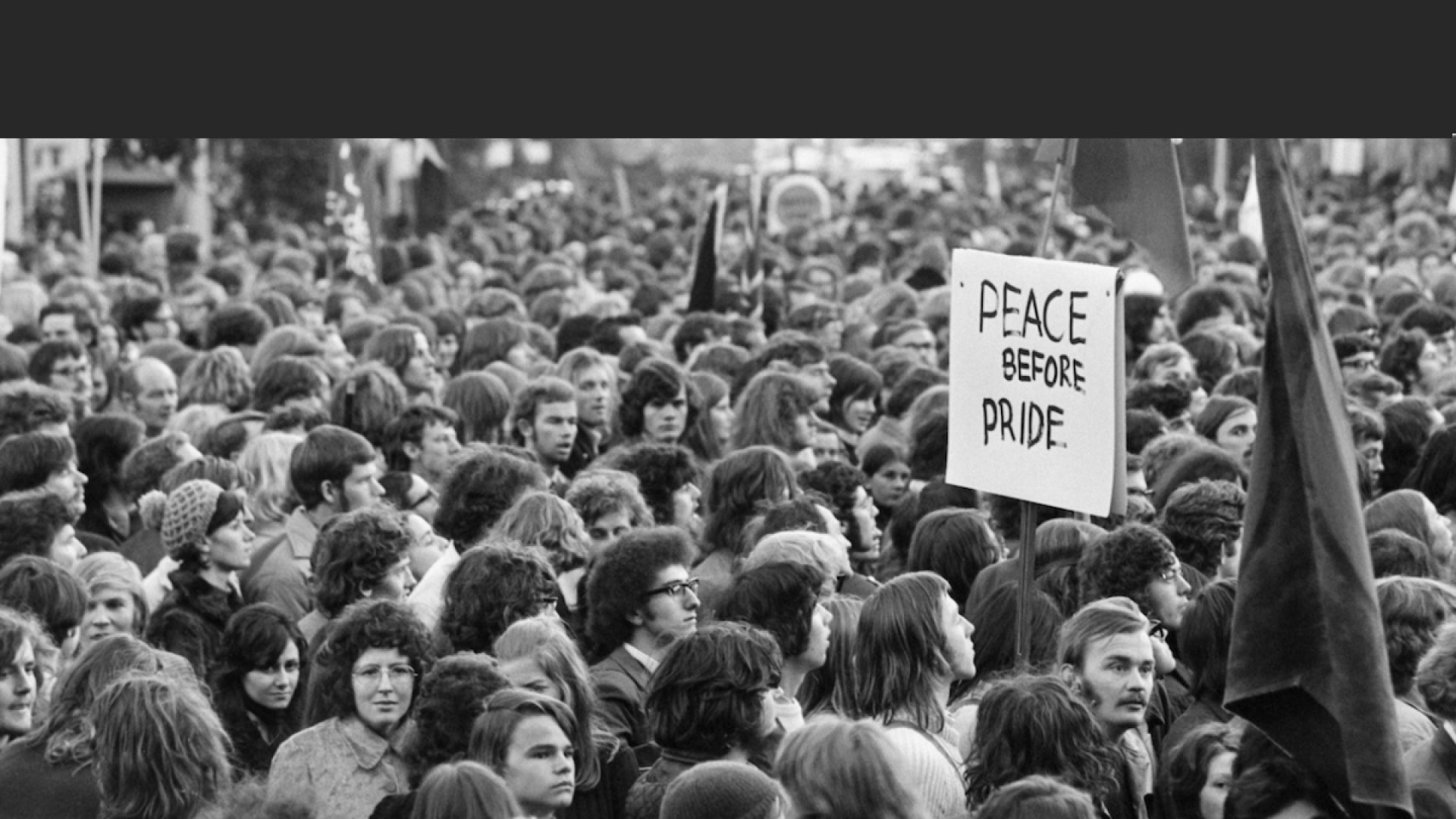

Bill loathed and detested war, and war mongers. When he migrated to Australia in 1948 and became an Australian merchant mariner and SUA member, he also joined the Communist Party of Australia and became Secretary of the Australian Peace Committee. In 1982 he marched in New York in the One Million March against nuclear weapons and the arms-race, rated then as the largest political demonstration in American history.

Despite his loathing of war, Bill wore his merchant-marine war service medals with pride. It was not pride in the service of war, but pride in the service of peace, his way of saying I fought against fascism, and now I’m fighting against war, and standing up for peace and social justice – and I know what I’m talking about because I have done the hard yards. It was alongside him on the Sydney Patrick’s Dispute picket line in 1998 that I stood with Bill and his medals.

Pugilistic skills were part of Bill’s maritime accoutrements, and in his time he was strong and well- built. As he succinctly remarked probably more than once, “I’ve met some bad bastards in my life, but they didn’t come up to me more than once”. During the height of the Cold War when SUA leader E. V. Elliott (1902-1984) was often physically threatened in the roughhouse of anti-union and anti-communist forces in the maritime industry, aided and abetted as this was by spooks, bosses, and a gaggle of right-wing forces, Bill was one of his protectors.

When I met him he was part of a select group of trusted SUA members Elliott variously deployed nationally, and internationally, to sort out industrial problems, and to initiate and/or advance union policy. Having said this, it should also be said that Bill was essentially a gentle person, his strength was always in reserve, and words, often expressed in a forthright way, came before the toughness; and he was modest despite his skills and experiences.

Alongside ‘war’, Bill ranked ‘racism’ in his detestation; it was something he often said in his maritime way that he “couldn’t fathom”. His international experiences of maritime work and life had taught him that a ship was both a machine and a community, and a safe voyage depended on people doing their duties, working together, attending to detail, and exercising their skills. It did not matter about colour or creed, it all came down to something basic and human. As Bill once wrote: “If a bloke needs a hand, you give him a hand. You go to sea and, unless you can rely on your shipmates, you’re dead. Your shipmates are your background, they’re your sidearm, they’re your everything”.

Historian Marcus Rediker, drawing on a typology developed by Walter Benjamin, has described a genre of storytelling he terms the “sailor’s yarn”. Rediker weaves this into his account of the origins and spread of Atlantic political radicalism during the eighteenth/early nineteenth centuries, stories/yarns based on the experiences of travel, different cultures, and maritime work, and drawing from these something of use to the listener, useful information on many human issues, and the necessities of resistance, struggle, and collective action. Bill was part of this maritime yarning tradition, and as a young historian learning the ropes, I was influenced and owe him a debt.

So thank you Bill for many things – for being a conduit to the worlds of the sailor and seamanship; for being part of my education and development, in effect providing an organic grounding in history from below by helping me understand the seafarer as a maker of history; for your personal examples of integrity, loyalty, and resilience; but mostly for your demonstration that a life lived in opposition to the Big Battalions can have worth, dignity, style, and humour, and that the Big Battalions are not invincible.

Rowan Cahill is an honorary fellow at the University of Wollongong.

NOTES

For an obituary of Bill, see “Vale William Horace (Bill) Langlois”, The Maritime Workers’ Journal, Summer 2015, p. 70. I have mentioned Bill previously as the ‘Ancient Mariner’ in “Flags of Convenience: Shipping Industry Patriotism”, Overland No 174, 2004, pp. 140-144. The SUA history: Brian Fitzpatrick and Rowan Cahill, The Seamen’s Union of Australia, 1872-1972: A History (Sydney: Seamen’s Union of Australia, 1981). For Elliott’s trusted SUA group, see Rowan Cahill, Sea Change: An Essay in Maritime History (Bowral: Rowan Cahill, 1998), p. 20. The discussion of the ”sailor’s yarn” is in Marcus Rediker, Outlaws of the Atlantic: Sailors, Pirates, and Motley Crews in the Age of Sail (London: Verso, 2014), pp. 9-29.

I was very sad to find the news of Bill and Gloria today I have been sick myself and found it difficult to contact the nursing home

He had assured me some one would lmet me know if he passed

He was the most amazing person I ever met loved having long conversations with him

And Gloria would potter in the background he took me to draw the lottery once and he used to meet me whenever I went to Sydney we called him

Uncle Bill and he was my mate

Just wondering where Bills son David was