By Hall Greenland

It is the season for centenary commemorations of the Great War. In the past months: the battles at Pozières, Mouquet Farm, Fromelles, and the Somme. The great and the good have been sorrowful and respectful of the fallen – as they should be. Lest we forget? No way.

Just don’t mention the war at home. On the home front there was bitter conflict, too. Strikes, riots, sabotage, police raids, surveillance, frame-ups, show trials and jailings. All this strife and tumult came to a head around the conscription referendum of 28 October 1916. In that poll a hundred years ago, the No side won narrowly by 71,549 votes.

This is the centenary that official Australia wants to forget.

Neither the Australian War Museum nor the Australian Museum of Australian Democracy, for instance, is planning commemorative events or exhibitions.

A spokesman for the AWM says its mission is to commemorate those who served in wars. But surely the fact – according to observers on the spot – that a majority of the men on the Western Front roused themselves from the blood and slush of the trenches to also vote No, reinforces the case for a special centenary event to mark the referendum.

The reluctance of the Australian War Memorial can perhaps be understood when you recall that the case for conscription, propounded by all the respectable elements in society, rested on the argument that Australia was not pulling its weight in the war. To recall this rather undercuts the current official narrative of the nation’s heroic response in the First World War.

The embarrassment is rather compounded when you realise that those who favoured conscription (including Australia’s generals) were defeated – in the then prime minister William Morris Hughes’ words after the poll – by an unholy alliance of syndicalists, IWW revolutionaries, Sinn Fein-ers, shirkers, red raggers, and selfish farmers.

The Museum of Australian Democracy has an even less convincing alibi. The referendum of 1916 – and its replay in 1917 – is arguably the most democratic event in Australia’s history. We were the only sovereign nation involved in the war that actually submitted the question of conscription to the people. In every other case the government just legislated for it.

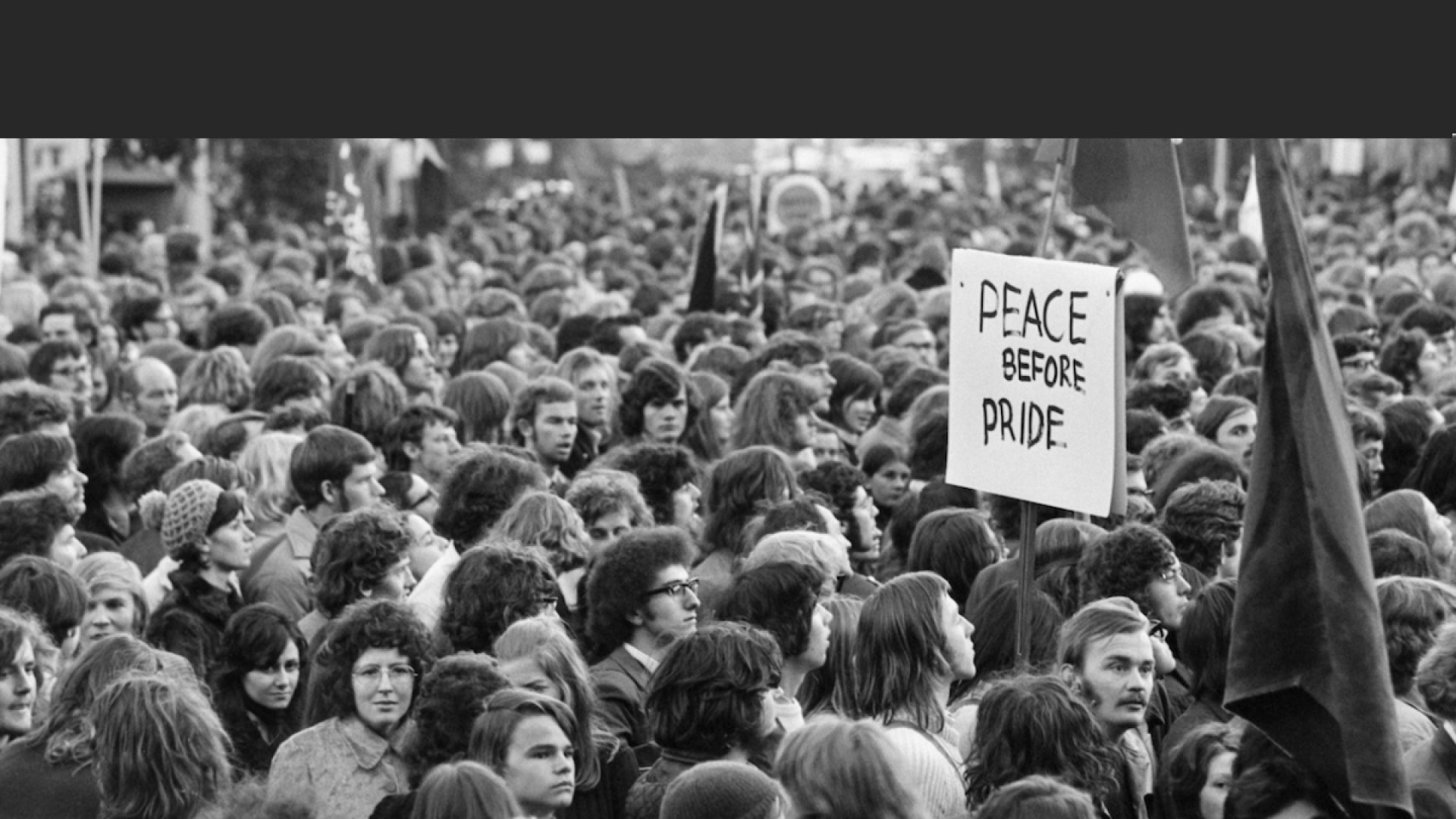

It was as well a thoroughly Athenian moment in our history. Hundreds of thousands of citizens attended rallies for and against conscription held on street corners, in union and town halls, in churches and masonic lodges, and at those great free speech arenas like the Sydney Domain or Melbourne’s Yarra Bank. There were even meetings for the soldiers at the front.

On the day itself the voter turnout (compulsory voting wasn’t introduced until 1924) was an extraordinary 83 per cent – an increase of ten percentage points over the previous federal election. The result was 1,087,332 votes for conscription, 1,158,881 against. The national majority of 71,549 can be credited to NSW where the No majority was 117,739 votes.

The issue split the Labor party. The Labor prime minister, his principal cabinet ministers and most of Labor’s state leaders campaigned for conscription. Ordinary party members and a minority of their MPs campaigned against. Historians like the late John Hirst have argued that the split changed Labor from being the natural party of government to an occasional tenant of the government benches.

Admittedly the democracy on show during the referendum campaign wasn’t pretty. It was insurgent. It had to be. Those that opposed conscription had the cards stacked against them.

All the better class of people lined up in favour of conscription. The prime minister, five of the six state premiers, all the leaders of the opposition, the churches (except for a handful of dissenters), judges, magistrates, the employers federations, the chambers of commerce, the masons, universities, the ex-servicemen’s associations, sporting heroes, iconic poets and naturally army officers – all supported conscription for the front.

The mass media then was the newspapers and all the country’s major city dailies were staunchly pro-conscription. The journals that were anti-conscription were heavily censored and on occasion seized and burnt or pulped.

There were plenty of reasons for the conscriptionists, led by the popular Labor prime minister William Morris Hughes, to feel confident of winning. At the end of July, Hughes returned from six months in Britain where he had been feted by the ruling class – “he never met anyone below a duchess” quipped his Labor critics. He had been made a de facto member of the British Cabinet, spent a weekend with the royal family at Windsor castle, had been granted the freedom of major cities, had honorary degrees conferred on him by Oxford and another half dozen universities, and had his speeches reported on the front pages of the British, Australians and French (!) newspapers.

When he returned to Australia he toured the country as “a conquering hero”. “Rarely has any man received so enthusiastic reception”, according to Ernest Scott, then the doyen of Australian historians and author of the official Australia During The War. In every capital city there were “scenes of enthusiasm unparalleled in Australian history”, writes Hughes’ biographer Laurie Fitzhardinge.

No sooner had Hughes returned than he received an appeal from the Australian and British generals for major reinforcements for the Western Front. The battle of the Somme had begun and casualties were enormous. By this stage volunteers had fallen to 6,000 a month and the generals were demanding 32,500 men in September and 16,500 per month thereafter. Conscription was Hughes’ way of making up the shortfall in heroes.

However, Hughes had been away too long. Throughout 1916 there was plentiful evidence that union and Labor party members were radicalising and escaping the control of their traditional leaders. There was a wave of unofficial strikes by miners, wharfies, shearers, and railway men.

In Hughes’ absence, union and state Labor Party conferences had decided to oppose conscription for overseas service. The votes had been overwhelming. At the inter-state union conference held in Melbourne in May 1916, for instance, the card vote against conscription was 738,000 to 700. On his return when Hughes failed to declare against conscription, the AWU’s newspaper the Worker told him: “It has been decided already. The Labor movement has made its mind known.”

Hughes’ opponents had been given plenty of notice of the conscription danger. In July 1915 the Labor government had decided on a wartime census of males between the ages of 18 and 45. While Hughes explicitly disavowed any plans to conscript men for the front, socialists and pacifists did not believe him and began forming anti-conscription organisations across the country. Simultaneously the conscriptionists formed the Universal Service League to campaign for conscription.

The unions and Labor party initially responded to the threat of conscription of men by demanding the conscription of wealth. What they meant by this was 100 per cent taxation on incomes from rents, interest and profits above £300 a year and a lien on the wealth of the rich to increase the capital base of the government-owned Commonwealth Bank. When Hughes abandoned even a promised referendum on price controls in December 1915 (food prices had risen 24 per cent during the year), he cut broad swathes of the movement loose to oppose conscription. Clearly there was to be no equality of sacrifice.

After prevaricating for a month after his return, Hughes opted for conscription on August 30. While he could command a majority for conscription in the House of Representatives, made up of pro-conscription Labor MPs and Liberals, he knew he was stymied in the Senate. There Labor had 31 of the 36 senators and while 11 proved to be pro-conscription, their defection would not have been enough to carry conscription legislation. So Hughes took another route. At the end of August he convinced his cabinet and caucus – by a majority of one in each case – to support a referendum on the issue.

There was a hardcore of Labor MPs who opposed the very idea of a referendum to compel men to kill or be killed. Frank Brennan, the first Labor MP to respond to the referendum bill when it was introduced to parliament on 14 September, argued that “there are questions upon which a majority, however large, has no right to coerce a minority however small”. This theme was to be the dominant one for the No campaign. Henry Boote, the editor of the Australian Worker and the principal propagandist on the No side, put it more poetically, “you cannot by counting heads, dispose of a question that belongs to the province of the soul. In this respect, the personal will is supreme and sacred.”

In announcing the referendum Hughes made it clear that he was making this appeal to the people at large in order to overwhelm his opponents within the Labor ranks. He was confident of a victory for the Yes side in the poll – “I believe the people of Australia will carry this referendum by an overwhelming majority”. He added that the Senate (and the rest of the Labor party) would then have no alternative but to pass legislation bringing in conscription.

Hughes promised the fight of his life, and he delivered, visiting all states save Western Australia and addressing appreciative crowds wherever he went. Boote described those attending his meetings as

“…the Point Pipers and the Elizabeth Bayites, the habitués of the golf links and the bowling greens, bald-headed fire-eaters over military age, a sprinkling of Labor renegades, the rag-tag and bobtail of Sydney’s snobocracy, and all their sisters, cousins, aunts, and poor relations.”

Maybe so, but an emboldened Hughes – now dubbed “the little Welsh Kaiser” by his Labor opponents in honour of his country of birth – issued call-up notices to single men aged 21 to 35 at the end of September so that they would be ready for dispatch overseas when the referendum was carried.

Equally provocative was his use of the “terrorist scare” during the campaign.

At the end of September, 12 leading members of the politically rumbustious and anti-war Industrial Workers of the World were arrested in connection with the burning down of a handful of warehouses in Sydney. They were charged with arson, sabotage and sedition and their trial began on 12 October. Earlier IWW members had been arrested in connection with the forgery of five-pound notes and the fatal shooting a policeman. Hughes had no scruples about linking the accused and their alleged misdeeds to the anti-conscription campaign and his leading opponents in the Labor caucus, Frank Anstey and Dr Maloney (a year before they had written letters of sympathy to Tom Barker, an IWW journalist sentenced to 12 months jail for an anti-war poster and the letters had been discovered by police in a raid on the IWW office in Sydney).

While the auguries were good for the Yes side, the anti-conscriptionists struggled even to be heard. Their publications were censored and confiscated; their offices raided and military censors installed; their publicists and speakers fined and sometimes jailed (including the future Labor prime minister John Curtin).

Initially they were literally chased off the streets by soldiers and patriots. Even in Broken Hill, the legendary citadel of militant unionism and political radicalism, when the anti-conscriptionists held their first main

street meeting on 4 August it was broken up by pro-conscriptions. The mob then moved on to wreck the hall of the anti-war Industrial Workers of the World. There burly local union leader Jack Brookfield blocked the stairs and while police looked on fought off the attackers.

Brookfield was arrested at the end of the affray but released next day in time to help organise a crowd estimated at 10,000 who marched back to the spot where the meeting had been overwhelmed the night before. The anti-conscriptionists never again ceded the streets of the silver city to their opponents.

In less dramatic form that pattern was repeated elsewhere. Conscriptionist squads regularly broke up the antis’ meeting on the Domain in Sydney until the Labor Party called its anti-conscription meeting on 13 August. Tens of thousands responded to the call and kept at bay the few hundred soldiers and their supporters who tried to storm the platform. This experience was repeated in Melbourne, Adelaide and Brisbane.

The winning of these free speech battles was an important fillip to the antis. After the Domain triumph, Henry Boote reported in the Worker that the meeting was

“the greatest gathering of men and women ever witnessed in Australia in the whole course of its history … We only wish that William Hughes had been there. It would have been the end of his coqueting with the capitalistic Potsdammers of this country”.

The next morning’s newspaper reports would, in Boote’s view, have been sober reading for the “bald-headed Prussians of suburbia”.

The campaign was fought at a fever pitch reflecting how deeply both sides felt about the issues.

The Yes side argued that a failure to carry the referendum would amount to letting down your mates in the trenches. It would also let down Britain – “home” to many Australians – and pave the way for a German invasion of Australia.

The No side responded that Australia was doing enough. Conscription would soon exhaust the supply of single men and the government would then come for married men. The Noes could also point to the censorship of left-wing and Labor papers, the fines and jailing of opponents, the refusal of exemptions to conscientious objectors, and the frame-up of the IWW Twelve as examples of the “Prussian militarism” that came with conscription and which Australia was supposedly fighting the war to resist.

The Easter 1916 Uprising in Dublin and its brutal repression rallied Irish Catholic Australians to the No cause. Why would they want to help Britain? Events in Ireland “struck in the hearts of the Irish-Catholic population of Australia chords which harmonised with the ping of bullets in the streets of Dublin rather than with the roar of artillery in Flanders”, to quote Scott’s jaundiced view.

More controversially the No side – or a large part of it – argued that the depletion of the male workforce by conscription would lead inevitably to the import of coloured labour and a general reduction of wages and conditions. This appeal to defend White Australia always embarrasses latter-day champions of the No side. Hughes, for his part, cited the threat from Japan as a reason to support conscription as a way of securing future Britain protection.

The xenophobia of the times cast a wide net. When 98 Maltese workers landed in Australia during the campaign – and news broke that another 200 were en route – this was seized upon by the No supporters as proof that the threat of coloured labour was real.

There can be little doubt that the defeat of conscription in the 1916 referendum was a triumph of the Labor movement – at a time when the majority of workers in key sectors of the economy were in unions. This is something that historians of the left, right and centre such as Ian Turner, Ernest Scott and Laurie Fitzhardinge all agree on.

“The greatest single cause of defeat, however, lay in the patient and pervasive organisation of the unions, with their ready made network of branches and their tradition of solidarity. They provided a vehicle for organisation and solidarity which far outweighed the effects of the press and the censorship on the other side,” wrote Fitzhardinge.

Confirmation of this can be found in the 12 October issue of the Worker with its schedule for the following week of 87 meetings in NSW country towns organised by Labor and the unions.

Both Scott and Turner credited the Industrial Workers of the World for their influence on the mainstream of the Labor movement – mainly in spreading among ordinary members a more critical attitude to their leaders. In addition, as Verity Burgmann has pointed out, the Wobblies’ call for a general strike to stop the war made anti-conscription appear moderate and reasonable.

Fitzhardinge and Scott singled out “the brilliant propaganda” of Henry Boote. He was arguably the finest (and the most effective) journalist of the times. As editor of the weekly newspaper of the biggest union in the country, Boote was given a free hand by the anti-conscription leaders of the union. He was himself opposed to the war. His lover and companion Mary Lloyd (they could not marry because Boote’s Catholic wife could not give him a divorce) has left a fragmentary record of the wars years at The Worker in the form of letters to her brother Will in Brisbane. They detail Boote’s battles with the military censors and the exponential growth of the paper’s circulation during the campaign.

Nevertheless, the No side would not have won based on the Labor movement alone. It is safe to assume that the Labor anti-conscription vote approximated 44 per cent of the total vote. This is the vote Labor received in the May 1917 federal election when the party was thoroughly in the hands of the anti-conscriptionists. Yet the Noes won with 51.6 per cent of the vote. So where did the extra 7-8 per cent of votes come from?

The anti-conscription stand of the then Catholic coadjutor archbishop of Melbourne, Daniel Mannix, is often cited as a central contributing factor. But the brutal repression of the Easter Rising in Ireland had probably already alienated the Irish Catholic voters, most of whom were working class and Labor supporters in any case. Even Mannix’s best known disciple, B.A. Santamaria, credits him with a very minor role in the 1916 result while claiming a major role for him in the second 1917 referendum.

For a long time a decisive role was ascribed to German farmers in South Australia but more recent research has revealed that there were fewer than 12,000 voters with German names on the voting rolls in rural and regional SA.

Turner however does credit farmers generally for swelling the No vote:

“Ultimately the defeat of the referendum came down to this: a good season, and a shortage of labour … it was the non-Labor farmers who defeated the government’s proposals.”

Murray Goot in a forthcoming book disputes Turner’s analysis. In three states the rural vote did favour the Noes, but in the other three it did not. In Australia as a whole the rural and regional vote against conscription was only 1.3 per cent higher than in the cities. Did farmers constitute this one per cent or could it equally have been itinerant bush workers, tradesmen, small shopkeepers or even government employees?

On the other hand, Goot believes women deserve a special mention in dispatches. His argument is that we do have a large sample of the attitudes of male voters – the soldiers overseas who voted 55-45 per cent in favour of conscription. If that is representative of general male opinion, then women must have voted No in greater proportion for there to have been an overall No majority. “The idea that it was the votes of women that turned it around is not entirely fanciful,” Goot writes. The anti-conscription handbill, “The Blood Vote”, a poem by W.R. Winspear and illustrated by Claude Marquet, aimed at women, was the most stunning piece of propaganda of the campaign.

The No victory, then, had many parents. The anti-conscriptionists had their deep differences – the Wobblies and socialists denounced the xenophobia of some of their Labor allies – but all parties converged on their opposition to conscription and were successful against the odds

The Yes side was stunned. The spluttering vitriol with which Hughes greeted his defeat showed how angry and uncomprehending he was.

True, the celebrations on the No side were short-lived. In December the IWW 12 were convicted and received ten and 15-year jail sentences. It was four years before a royal commission quashed the convictions. In the aftermath of the referendum Hughes and his supporters walked out of the Labor party and fused with the Liberals to form the Nationalists. This new party won an overwhelming victory at the federal election in May 1917. The new government promptly outlawed the IWW.

With volunteer numbers continuing to fall, Hughes tried a second conscription referendum in December 1917. He lost again and the No majority nearly doubled.

Not once, but twice, the Australian people showed their ruling class that they could not be counted upon to toe the establishment line, even in wartime. What’s not to like about that? It calls for celebration as well as commemoration.

Such a helpful article at this important time

A very good article, but there is some official recognition of the referendum’s centenary: Australia Post has issued a stamp.

So much was done in the name of saving workers from an imperial war, this story gives us a rich description of the proud tradition of people opposing the elites of our society. People should understand our history to see where we are going

An excellent article here from Hall Greenland.

The 55%-45% split in favour of conscription from the troops actually involved on the battlefields is surprising in that so many of them (the 45%) were against conscription.

“…On the other hand, Goot believes women deserve a special mention in dispatches. His argument is that we do have a large sample of the attitudes of male voters – the soldiers overseas who voted 55-45 per cent in favour of conscription….”

As all of those troops were themselves volunteers, one wonders why so many of them were against. It is not that they did not themselves believe in the cause. As far as popular attitudes of the day were concerned, the ‘Great War’ was started by the Kaiser’s forces going on an unprovoked rampage through Belgium. (See Barbara Tuchman, ‘The Guns of August’.)

It would appear to me that the most common concern among the troops was likely the character of the society they were fighting for, and what effect conscription would have on it. Would a conscriptionist Australia be a country worth returning to? The German enemy army was built by conscription. To what extent did that army and the society which produced it serve as a negative example?

Bob Menzies was a member of the Melbourne University Rifles, but resigned at the outbreak of WW1. (“A most promising military career, unfortunately cut short by the advent of war” – Sir Wilfred Kent-Hughes.) Yet he went on to preside over conscription in Australia for Vietnam: a matter in which I had a personal interest, as I had been conscripted for National Service training in 1958, served in the CMF till 1962, and was on the reserve list until 1968. But Menzies did not want us. My guess is that he decided it would have been politically impossible. My fellow conscripts were all starting careers, families etc by the time Vietnam started.

Best to grab the poor bloody 18 year olds and send them.

Incidentally,does anyone connected to this site have any information on the reason/s for the confounded print being so faint?

Some sort of electronic economy drive perhaps?

A desire to confer extra authenticity and authority: by making it all look as if the documents have had all the contrast leached out of them from lying below the water table since the day they were written?

There must be some deliberate reason.. It can’t be an accidental oversight.

Can it?

Hi Ian. I’ve changed the font – I didn’t realise it was hard to read. Let me know if this one is any better. Cheers, Julie