Frank Bongiorno

Many of us owe a very great debt to Dr Sigrid McCausland, whose untimely death on 30 November 2016 has been widely mourned by her many friends and colleagues in the archival and historical communities. The biographical notes at the end of Light from the Tunnel, a history of the Noel Butlin Archives Centre at the Australian National University published in 2004 to celebrate its survival, called Sigrid McCausland’s part in defending it ‘the greatest struggle of her professional life’.

I suspect these words were Sigrid’s own, and they are unerringly accurate. As University Archivist Sigrid became the central figure in the campaign to save the archives, and she brought to that struggle a passion and commitment that had personal and professional costs. At one point the ANU management formally forbade Sigrid from having anything to do with the Noel Butlin Archives, so that it could roll out its latest hare-brained scheme for closing the place while maintaining the appearance that it was still functioning. ‘To have your work denigrated and to be told by others without expertise that it is dispensable’, she later reflected, ‘was extremely unpleasant’.

Sigrid’s arrival in Canberra as University Archivist in November 1998 was an especially lucky break for those who wanted to save the archives. The Director of the Research School of Social Sciences had announced their imminent closure and foreshadowed the dispersal of the collection in August 1997. The future of this monumentally important national collection was still very much in doubt when Sigrid arrived; as if to make the point, the ANU initially put her on a three-year fixed-term contract. But she brought to her role – one she would play with skill, tact and vision until 2005 – an extraordinarily rich store of expertise and wisdom built up over an already long and distinguished career in archives.

There was also something about Sigrid – a calmness, poise, humour and dignity – that instilled confidence in others, and gave her arguments that extra force they needed in difficult days. At a time when there was considerable anger over the behaviour of the ANU – and with many provocations still to come – she revealed an acumen that was sorely needed. She once told me that someone from the university took her out to a site in outer-suburban Canberra that the university management had in mind as a replacement for the Acton Underhill as storage. Sigrid didn’t like the look of it and rejected the idea; wouldn’t it be vulnerable to a fire? Sure enough, the Canberra bushfire of 2003 soon swept through the area. Possibly, without Sigrid’s wise counsel, the records of the Australian Agricultural Company – whose place on the UNESCO Memory of the World Register she championed and secured – would today be a collection of cinders.

Sigrid also had the job of overseeing the new arrangements whereby the reading room and offices were moved into the Menzies Library, and away from the Acton Underhill. She understood that the move had its disadvantages. Researchers would need to order material in advance of a daily retrieval time, rather than simply walking in and getting their documents in a few minutes. But Sigrid also understood that the benefits from the move – in terms of assuring the Archives’ future – outweighed such minor inconveniences.

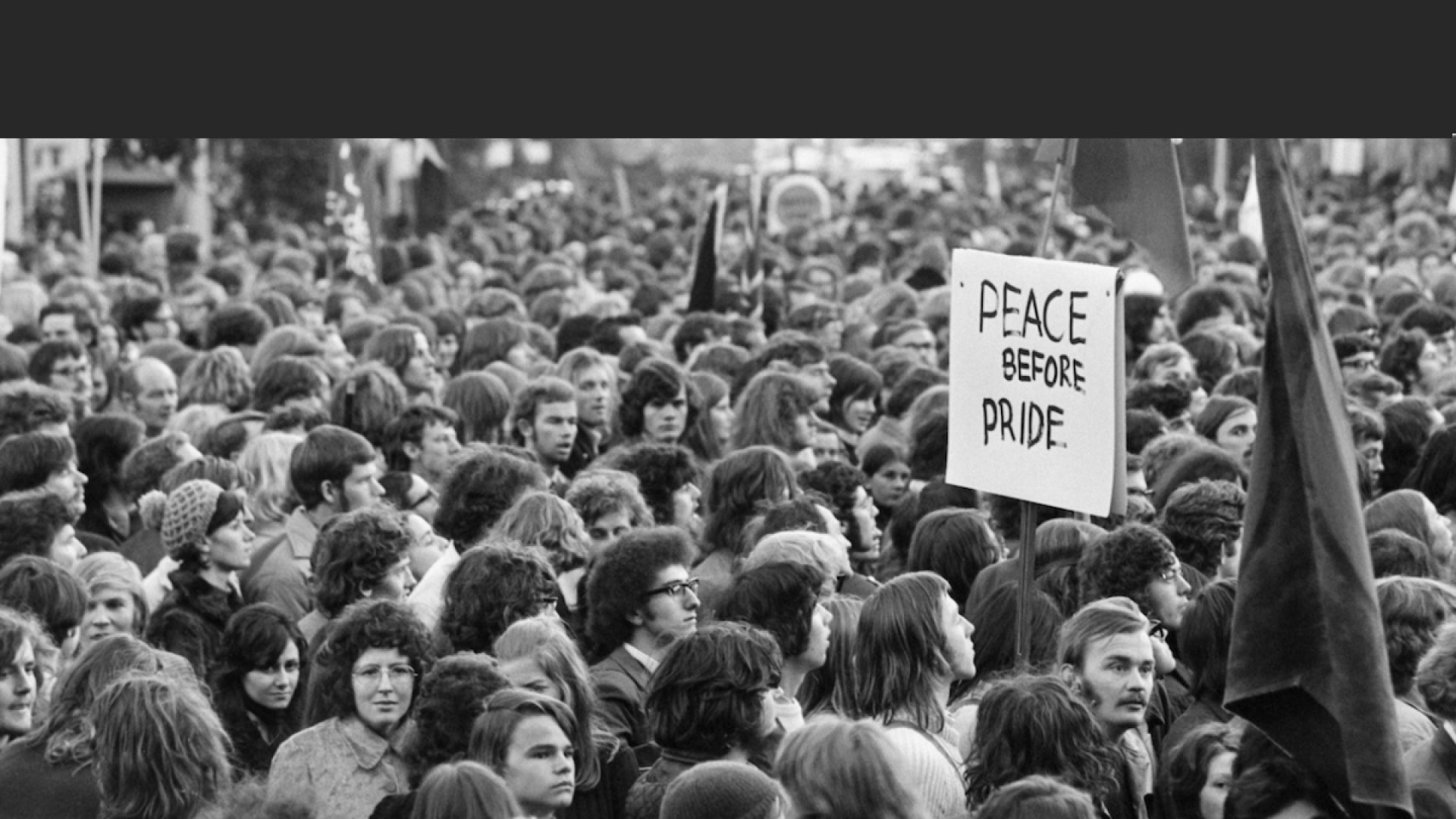

She was no stranger to the ANU. Having been raised in Bathurst – a connection with regional Australian life that remained important to her – Sigrid was an undergraduate at the ANU from 1971 until 1974, living first at Burton Hall and later, in a lively shared house while she completed an Honours degree in History with a thesis on modern painting in Sydney from 1935 until the end of the war. She was part of a talented Honours cohort, who were finishing their degrees at the time when student radicalism peaked at the ANU, in 1974. Canberra was then the home of Labour History, and the ANU the country’s major centre for study in the field; her teachers included Bob and Daphne Gollan, Humphrey McQueen, Bruce McFarlane and Bruce Kent, as well as Manning Clark, John Ritchie, John Molony and in Politics, Fin Crisp. Sigrid was a conscientious and successful student – although, by her own account, a perfectionist – whom Clark enlisted as his research assistant after she had finished her studies. She clearly didn’t allow herself to be overawed by the great man. Although he invited her to undertake a Master’s thesis, a year working for Clark was enough and she was soon heading overseas in a familiar rite-of-passage for young Australians of her generation.

Sigrid returned to a country in 1977 that was a much less inviting place for a young graduate beginning a career than it had been when she completed her degree. But she quickly found a job in the public service, working for a year in the housing branch of the Department of the Capital Territory. A year later she was at the Australian Archives, now the National Archives of Australia, but this was not her first encounter with what would become her life’s work; she had previously been employed during university holidays in the nissen huts next to the lake that were then the Archives’ home, working on Billy McMahon’s papers.

Sigrid later worked at the State Library of New South Wales, for a time in the Mitchell manuscripts collection, and she completed the archives course at the University of New South Wales in 1982. She would also later tutor in that course for a couple of years, the beginning of a lifelong commitment to archival education. After another period at the Australian Archives and an appointment as the City of Sydney Archivist, she became University Archivist at University Technology Sydney, where she also completed a doctoral thesis on the anti-uranium movement. It was submitted for examination just a few weeks after her appointment as University Archivist in Canberra.

Sigrid was recently made a Fellow of the Australian Society of Archivists, an honour that, among other things, recognised her long-term contribution to archives education. She contributed to editing the first edition of Keeping Archives, the Australian archives profession’s bible; served on the editorial board of the profession’s journal, Archives and Manuscripts; and, in recent years, returned to teaching, this time at Charles Sturt University, where she played a major role in the success of its undergraduate and postgraduate programs in archives and records management. She presented and published many papers, was active in her profession’s national and international organisations and, alongside her multiple achievements in a busy professional life, was an inspiring mentor and colleague to many younger archivists. Her international standing in the field of archives education received recognition when she was appointed to the prestigious post of Secretary General of the Section for Education and Training for the International Council on Archives.

The Australian Society for the Study of Labour History recently honoured Sigrid with its Gold Medal. Alongside her outstanding contributions to labour history as an archivist, she served as President of the Canberra Region Branch of the Society during her busy period as the ANU’s University Archivist, and she was more recently a valued member of the Brisbane Labour History Association executive.

Sigrid will be long remembered for her warmth, sense of fun, generosity and intelligence, as well as her remarkable energy and versatility as a professional in the worlds of history and archives. The labour history community feels her loss keenly. We offer condolences to Phil Griffiths, Sigrid’s partner, and to all of her family, friends and colleagues.

This obituary was originally published in The Queensland Journal of Labour History, no.24 March 2017 p. 62. It is reproduced here with permission.

Frank Bongiorno is an Australian labour, political and cultural historian, and Professor of History at the Australian National University.