Terry Irving

We’ve just come back, Sue and I, from four weeks in France and Spain, a very different holiday from our usual. Without a car, we walked a lot, in small towns and suburbs away from the main tourist attractions. And we discovered something tourism is not designed to reveal: traces of the collapse of the consensus that parliamentarism equals democracy, and that to neo-liberal austerity there is no alternative. We photographed posters, plaques, and hand-made banners that signified a history that is being made, and a past that is being remembered.

We arrived in France in October. Six months earlier, the left, as La France insoumise (France Untamed), had regrouped around the candidature of J-L Mélenchon in the Presidential election. The models for this regroupment were Podemos in Spain and the Bernie Sanders campaign. As social democracy collapsed, and the exposure of corruption damaged the conservatives, support for Mélenchon surged. He attracted about 20% in the first round of the Presidential election. This poster was in Sète:

In September there were massive street protests against President Macron’s revision of the labour code. A Leninist party, ‘The Weapon of Revolutionary Marxism’, which had advised workers not to vote in the election, called on workers to ‘blow-up capitalism’. But first they must stand in the street reading 1000 words of explanation – an example of revolutionary practice as futile as Percy Bysshe Shelley’s in 1812, as he dropped copies of his incendiary tracts on the heads of likely supporters from his bedroom balcony in Dublin. This poster was found in Béziers:

Also in Béziers, there was this appropriation/adaptation of the recent anarchist image for street occupiers. ‘To create is to resist’:

In the Thau, a series of lagoons in Languedoc, a co-operative movement was also part of the mobilization against Macron’s new labour law. It called for a strike and demonstration outside the town hall in Séte, but distanced politically from official labour: ‘Don’t take instructions. Let us organize the strike ourselves.’

From Béziers we went to Barcelona, arriving as the Catalan Assembly voted for independence. The opposition parties refused to attend the vote. The idea of Catalan independence – a new state, a new ‘country’ – is shaped by a section of Barcelona’s political elite; it is projected towards the middle classes; it is a form of identity politics. It is therefore an idea that the left regards with suspicion, because it suppresses a politics concerned with social need and planetary survival. But a history of Castillian contempt for the regions of Spain, and of the vicious stamping out of Catalan language and culture under the Francoist regime, means that the defence of Catalonia is very popular in the region. The left therefore is wedged by the issue of independence, supporting its popular character but demanding the insertion of social and economic issues into the debate about the region’s future. This is the mission of Barcelona en Comú, a feminist, participatory and co-operativist social movement to which the Mayor of Barcelona, Ada Colau, belongs. On all sides, however, there is agreement that Madrid is a powerful source of reactionary ideas and neo-liberal policies. Hence the emphasis in the Catalan nationalist propaganda on democracy and cultural difference:

From Béziers we went to Barcelona, arriving as the Catalan Assembly voted for independence. The opposition parties refused to attend the vote. The idea of Catalan independence – a new state, a new ‘country’ – is shaped by a section of Barcelona’s political elite; it is projected towards the middle classes; it is a form of identity politics. It is therefore an idea that the left regards with suspicion, because it suppresses a politics concerned with social need and planetary survival. But a history of Castillian contempt for the regions of Spain, and of the vicious stamping out of Catalan language and culture under the Francoist regime, means that the defence of Catalonia is very popular in the region. The left therefore is wedged by the issue of independence, supporting its popular character but demanding the insertion of social and economic issues into the debate about the region’s future. This is the mission of Barcelona en Comú, a feminist, participatory and co-operativist social movement to which the Mayor of Barcelona, Ada Colau, belongs. On all sides, however, there is agreement that Madrid is a powerful source of reactionary ideas and neo-liberal policies. Hence the emphasis in the Catalan nationalist propaganda on democracy and cultural difference:

Catalan culture is not threatened. Twelve percent of books published in Spain are in Catalan. But defense of Catalan traditions elicits strong feelings. We came across this ‘festa’ outside the cathedral in Barcelona:

But the language issue is also divisive. Half of the population in Barcelona speak Castillian and most identify with the Spanish state. And even Catalan nationalism has to recognise the survival of Occitan in the valley of Aran:

We spoke to Nick Lloyd (see below), who has lived in Barcelona for many years, about support for Catalan nationalism. He believes some of it can be traced back to family histories of victimisation of the republicans by the Madrid-based fascist regime after the defeat of the Republic in 1939. Remember, Spain now is a monarchy. These posters survived from the lead up to the ‘illegal’ referendum in early October. Vote ‘yes’: ‘Hello, New Country’; ‘Hello Republic’:

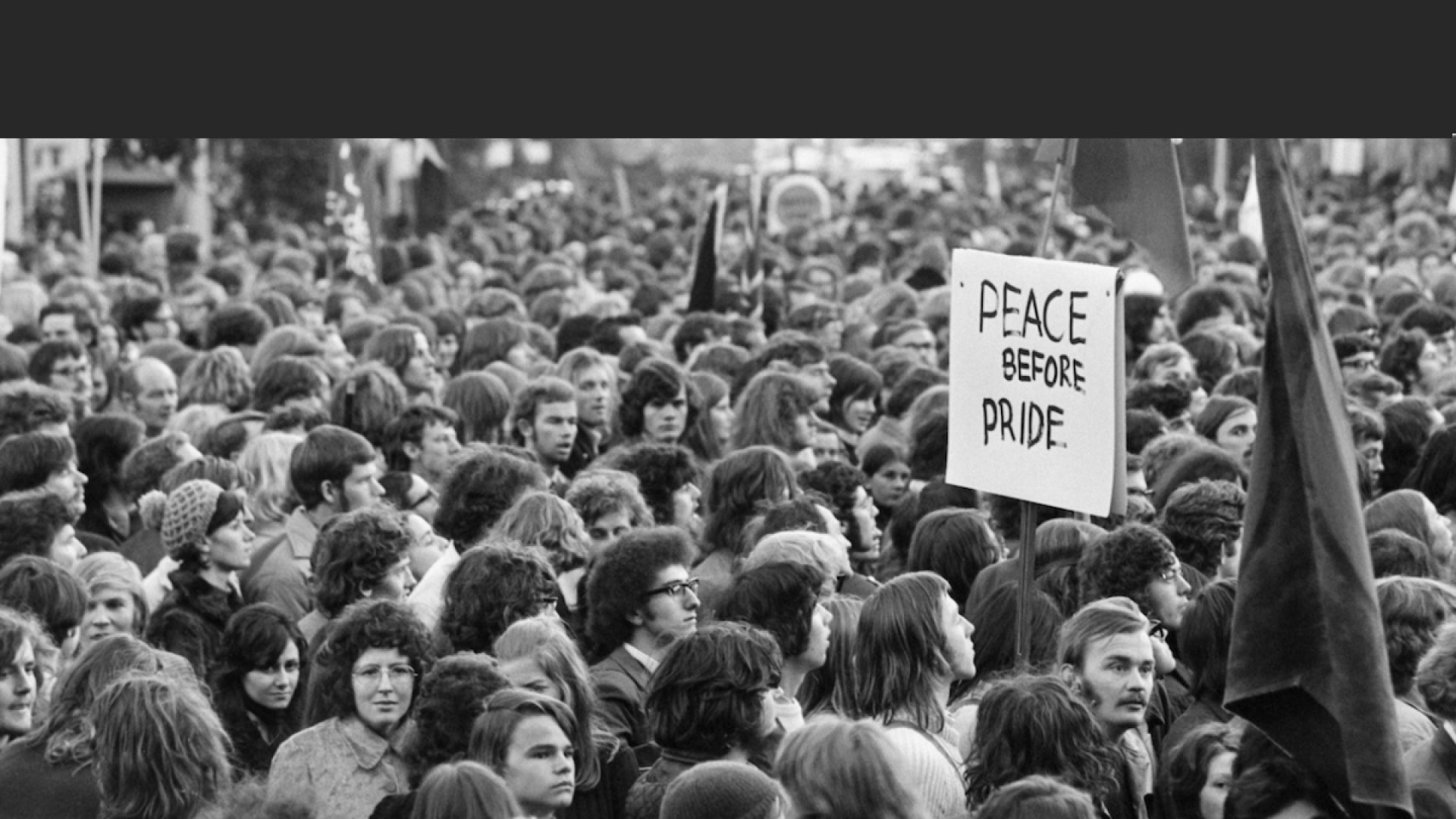

After the Assembly vote was announced, the people took over the streets, including the Via Laietana outside our hotel. The local police in their trucks were passively present; there were no disturbances. No indications of the role of an organising force; no marching; no imposed external discipline; no manipulated revolutionary intent. It was more like a flash mob than an uprising against the Spanish state. But the street was theirs: fuck-off cars; piss-off police. Some groups of young people were cheering; most of the crowd was thoughtful rather than excited. What would happen next? There was much talking, unlike the bored, resigned silence in the lines to the voting booths in our country:

In Barcelona, we went on one of Nick Lloyd’s highly regarded tours explaining the Spanish Civil War and Barcelona’s part in it. Here is the cover of his book, 388 pages of civil war history and a guide to hundreds of sites relating to it, crammed with photographs, and written with passion:

For a brief summer in 1936, Barcelona was collectivised by the rank and file of the anarchist union, the CNT, and the cadres of the Trotskyist POUM (the Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification – which Orwell supported). As Lloyd explains in the book, a revolution occurred ‘not only against fascism but also against the Spanish Republic and the Catalan Government, and therefore also against Catalan nationalism.’ (p. 63) Then the revolution was betrayed by the Communists and the liberal republicans. The POUM leader, Andreu Nin, was ‘disappeared’. This is a plaque in his memory, erected in 1983:

His exposition of the causes of the civil war, the heroism of the republic’s supporters, the betrayal of the republic by Britain and France, the horrific suffering of the republicans, bombed mercilessly by German and Italian planes until they surrendered, was very moving. Below is a rare plaque to the victims, erected only in 2003:

And, one of Nick Lloyd’s treasures, a contemporary postcard designed to publicise the bombing and elicit foreign support:

With Nick Lloyd’s help we found the anarchist bookshop – which closed as soon as we walked in! We said we wanted to look around; no, it was time to close. Could we buy some postcards? Yes, but shop closes now. We quickly gather up some postcards, pay and vamoose. That’s workers’ control in action! Bugger the bourgeois customers. Here’s the CNT banner hanging above the entrance. (The AIT is the anarchist farm-workers’ union; still strong in Andalucia):

In Barcelona, the distress to local communities created by tourism, has found a voice:

And in Seville local communities are resisting development. The Pumarejo is an 18th century palace owned by the city council but self-managed by the residents of the neighbourhood in the interest of cultural and social diversity. It participates in campaigns to limit the impact of tourism and redevelopment in the barrio:

La Macarena is Seville’s bohemian quarter. We found these signs of its alternative political character. ‘Resist the eviction. La Revo [lution]. Flowers for our dead.’

‘Women managing [autogestionada] their own lives’:

And supporting refugees and immigrants:

Seville’s local government erected a plaque to recognise the Communist Party’s resistance to the Francoist regime:

Historical memory is important to the Reds:

and to the Anarchists. Here they are nurturing the red and black political memory in their monthly program of lectures and performances:

Jose Antonio Primo De Rivera, aristocrat and fascist ideologue, was executed in 1936 for plotting to overthrow the Republic. His father had been Spain’s dictator between 1923 and 1930. In 1933 the younger De Rivera had set up the Falange, Spain’s fascist party. When Franco triumphed in 1939, De Rivera’s name, like that of other fascist ‘martyrs’, was often inscribed on church walls. We found his name on an external wall of the Cathedral in Seville.

Half a million people died in the civil war. Tens of thousands of Republicans were executed by the Francoist regime, while thousands more died in concentration camps. Up to 200,000 Spaniards died of starvation during the 1940s. Tens of thousands of children from republican families were stolen from their mothers and given to Francoist families. Half a million anti-fascists went into exile. Many died in squalid camps on the French side of the border, some in Argeliers, where Sue and I had just luxuriated.

Political memory, running deep and bitter on the Spanish left, still spurs action against the blood shed in those terrible years. Someone had remembered Jose Primo De Rivera not as a fascist ‘martyr’, but as an enemy of the people:

A wonderful piece – we need more of this kind of writing! Thank you

Eight hundred plus gathered in the Ballarat Town Hall to debate the merits of the Spanish Civil War in 1937 so it is fascinating to hear how it is still being played out in Barcelona. Thank you for sharing your impressions – there is real restlessness in many places.

Thank you for this below the headlines overview of the political commentary and mood in France and Barcelona. Documenting the signs of protest is especially interesting.