Phillip Deery

In August this year, a fascinating story appeared about the expressionist émigré artist, Danila Ivanovich Vassilieff.[1] Many Labour History Melbourne members would be familiar with the Russian-born Vassilieff, either through his remarkable paintings hanging in major Australian galleries, his inspiration for Sidney Nolan’s Ned Kelly series, the 2016 documentary film ‘The Wolf in Australian Art’, or his significant influence on the ‘Heide Circle’ of artists embraced by John and Sunday Reed. Indeed, it was at the Reeds’ home, Heide, that Vassilieff collapsed and died an early death in March 1958.[2] And it was at Heide in December 1958 that a memorial exhibition of 94 of his paintings and seven sculptures opened. The newspaper story focused on the recovery of Danila’s eight ‘marriage paintings’ of Elizabeth, whom he painted in their initial years together and to whom he was married for seven tempestuous years (1947-1954).

But there is another story, and it concerns her. Elizabeth Orme Hamill, née Sutton, was a 31-year-old teacher, writer and divorcee when they met in Warrandyte. Although Danila had an anti-communist background – he fought with the Whites during the civil war in Russia and was captured by the Reds[3] – Elizabeth, both during their marriage and well beyond, was not only an artist in her own right, but an activist in the peace movement and the Communist Party. And of this, we can learn more from her ASIO files that, to my knowledge, are used here for the first time. Covering 18 years, they begin in 1952 and end in 1970.[4]

Prior to 1952, we know that she was secretary of a Left Book Club in 1939 in Perth, lectured in modern literature for the Melbourne University Extension Board, published a book of literary criticism in 1946, These Modern Writers: An Introduction for Modern Writers, and tutored in modern art at the Council of Adult Education in 1948-49. She also wrote for Meanjin, edited its poetry and became its associate editor in 1951. She was bohemian in style but also relatively wealthy: she inherited considerable money from the estate of her father, Les Sutton, and was the beneficiary of an annual dividend of £200 from shares in his Sutton’s Music Store. In 1947, she purchased from the near-destitute Danila his hand-built stone and log house, Stonygrad, in Warrandyte (now on the Heritage Register) and financed all their-day-to-day expenses and his art supplies; he had ‘met a woman who owned a chequebook’.[5] (She later privately wrote: ‘Danila was always the TAKER–others were the GIVERS’.[6]) Danila, she confided to an interviewer, was apolitical; she was not.[7]

In 1952 Elizabeth travelled extensively. The Menzies government imposed a controversial passport ban on all delegates attending the Peking Peace Conference, but after protests the ban was revoked.[8] This enabled Elizabeth to depart in October for Beijing. As a delegate of the Fellowship of Australian Writers[9], she then attended the Soviet-backed Third World Peace Congress (December 1952) in Vienna where she met Paul Robeson and Pablo Picasso. From there she travelled to Prague and on to the Soviet Union where she attended the All-Union Conference of Soviet ‘Defenders of Peace’ on 2 December,[10] and the delegation was taken on numerous organised tours. She also intended to meet up with Danila – ‘see you in Moscow’, she wrote. But Danila never left Stonygrad, instead having an affair with a local barmaid, one of his many marital infidelities.[11] Her detailed observations of this 25,000-mile trip were published in her 300-page Peking-Moscow Letters: About a four months’ journey, to and from Vienna, by way of People’s China and the Soviet Union (1953); the Guardian judged it be ‘a warm, lively and witty book’.[12] She met the publication costs herself and wistfully, if ironically, commented in a letter to peace activists from whom she sought assistance, ‘Oh for a bag of Moscow gold!’[13]

She returned to Melbourne starry-eyed. At one of innumerable meetings she addressed in early 1953, and hosted by the Australian Peace Council, she described her visit to China and the ‘epic’ and ‘heroic’ Soviet Union as a ‘journey to another planet’.[14] She described the Czechoslovak people as ‘free, happy and contented’ at the very time Prague was being convulsed with the Stalinist purges of Communist Party leaders – the notorious anti-Semitic Slansky trials. But it was with ‘New China’ that she was most smitten; it was, she told a meeting, ‘the happiest place in the world today’. She visited a prison ‘where all the prisoners were singing songs’.[15] About China she wrote a three-part series of articles for Voice, a feature article in Mary’s Own Paper (published by Adelaide’s Mary Martin), made two ABC radio broadcasts, wrote numerous letters to newspapers, went on a month-long lecture tour in Western Australia (where she stayed with Katherine Susannah Pritchard),[16] and joined the Australia-China Society becoming its vice-president in 1957. All this was dutifully documented by ASIO.

What is not recorded in ASIO files was a report of an Australasian Book Society meeting on 21 November 1953 to hear Elizabeth talk about her Peking-Moscow Letters. One who was there was Tim Burstall. His diary entry gives us a partial insight into Elizabeth Vassilieff’s character, described elsewhere as ‘a woman of very definite opinions, very black and white’.[17] Burstall wrote:

Mrs Macmahon Ball had a short exchange with her over Hong Kong (which Elizabeth Vassilieff had used as typical of the Old China) and which finished up with Elizabeth saying scoffingly, “you can’t know China”, which was rather tactless considering the Macmahon Balls were there in 1947…I decided I didn’t like Mrs Vassilieff, either. Her manner was matey but cold.[18]

On other fronts, Elizabeth was equally active. In the 1950s she was heavily involved in the Australasian Book Society; the Realist Writers Group; the Realist Film Society (to which she donated £50 towards the cost of a film); session chair, 1953 Convention on Peace and War; the Australian Soviet Friendship Society; co-organiser, International Women’s Day celebrations; and public relations officer for the All Nations Cultural Centre. As ASIO noted, ‘She is an intellectual type’.[19] She was a regular speaker at the Yarra Bank on the ‘truth’ about China and Russia under the umbrella of the Victorian Peace Council and the Communist Party. At one Yarra Bank gathering, according to a Party member, Enid Morton (who told an ASIO informant), Elizabeth, in response to anti-communist hecklers challenging her on conditions in Russia, ‘made a complete fool of herself by claiming that her name was Bettina Elizabetha VASILIEFF [sic], a Russian-born subject with parents in Russia’. Morton was allegedly ‘incensed that such lies could be allowed by the Party…and used against the Party’.[20] Not surprisingly, her phone was tapped, indicated by the many ‘intercept reports’ in her ASIO files.

ASIO also recorded personal intimacies. When Danila went to Mildura High School to teach art – only two of all his paintings had been sold,[21] and he was, said Elizabeth, ‘very depressed’ – she had an affair with a communist organiser and waterside worker, Dave Rubin, himself the subject of six volumes of ASIO files. He borrowed, long-term, her Citroen car and was ‘cohabiting’ with her at Stonygrad.[22] In July 1954, ASIO questioned two private investigators outside Rubin’s flat, under ASIO surveillance, who stated they were ‘working for Mr. VASSILIEFF for the purpose of obtaining evidence against his wife and subject’. Soon after the Vassilieffs divorced. In December 1959, twelve months after Danila’s death, Elizabeth married a tall, blonde and blue-eyed German, Wilheim Wolf. He was killed in an industrial accident in 1964.

She retained her ideological myopia about the structural oppression of communist regimes. Less than a year after the purges and mass arrests of Mao’s critics in China during the ‘Anti-Rightist Campaign’ (1957-59), Elizabeth believed that China had ‘the most popular government that has existed in world history’. With the Soviet Union in mind she wrote, soon after the Cuban Missile Crisis, that communism was ‘a social challenge, not a military threat, a world-wide historical development’.[23] Where many other Communist Party intellectuals had drifted away, resigned or been expelled after the tumultuous events of 1956 (Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin and the Soviet invasion of Hungary), she kept her faith and stayed on.

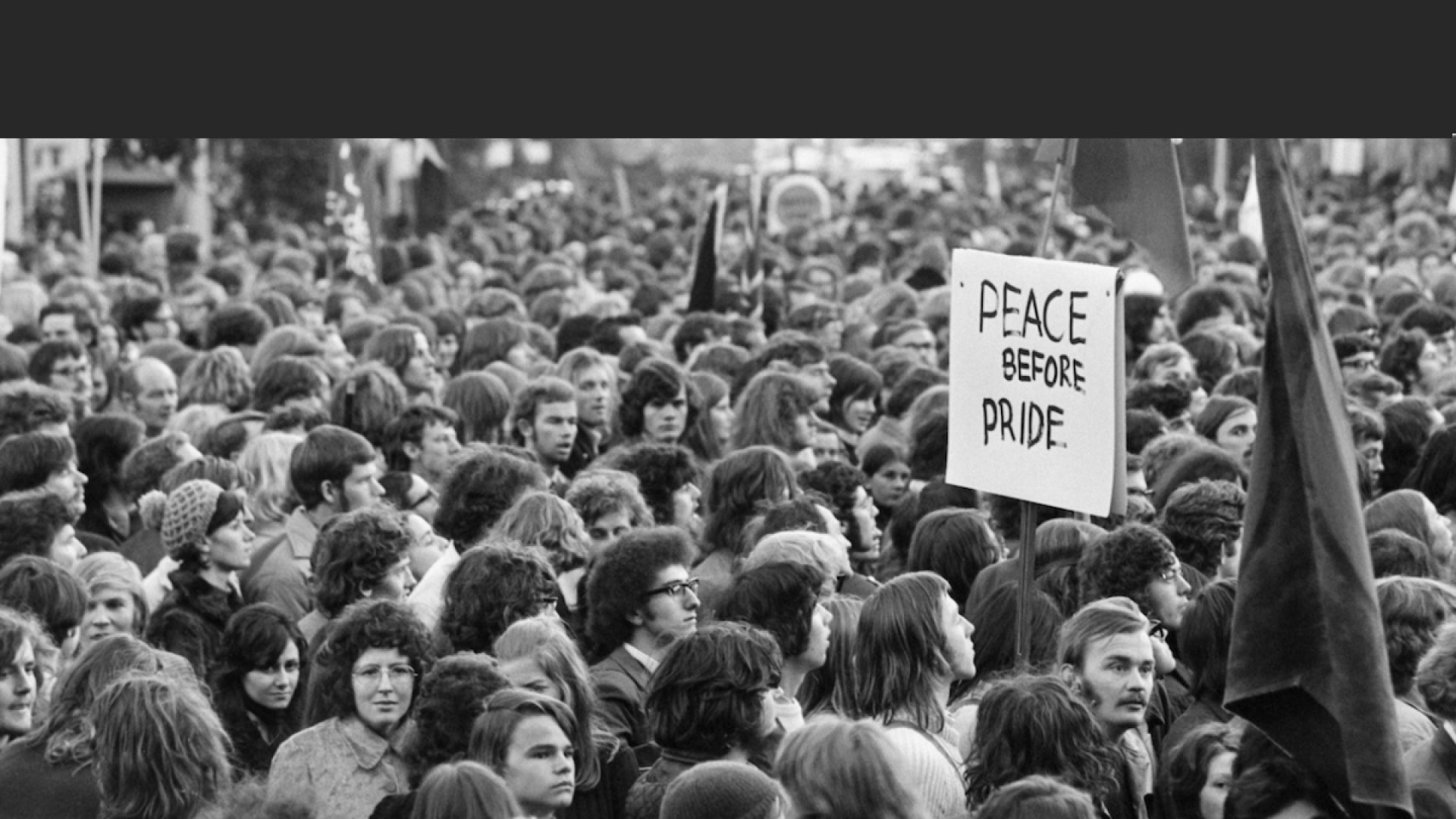

Her final marriage, in March 1965, was to the radical AWU unionist Pat Mackie, the iconic unofficial leader of the 7½-month long Mt Isa strike in 1964-65. Dave Rubin had been assigned by the Communist Party to look after Mackie during a speaking and fund-raising tour to Melbourne; this included a gathering at Stonygrad (where he and Elizabeth first met).[24] ASIO records that Mackie was to have addressed a Trades Hall Council meeting on 11 February but was reportedly too inebriated, evaded Rubin and left for Warrandyte. In February 1965 Elizabeth travelled to Queensland and married Mackie in March.[25] They returned to Stonygrad and attended the first public protest meeting against the Vietnam war, in Richmond Town Hall on 23 May 1965.[26] They co-wrote Mount Isa – The Story of a Dispute (1989) and she edited Mackie’s autobiography Many Ships to Mount Isa (2002). They lived together in Sydney until her death in 2007 at the age of 92.

The newspaper article, mentioned at the beginning of this article, did not refer to Elizabeth being a prolific painter in her own right, sometimes combining with Danila to hold joint exhibitions. Her first exhibition was in 1949; the last in 1987.[27] Often she, unlike he, blended art and politics, exemplified by her ‘Peace worker accused of treason’ (1952). An exhibition of her paintings was planned for late 2019, but has not yet eventuated.

REFERENCES

[1] Tiarney Miekus, ‘Just one catch, made in heaven’, Spectrum, 8 August 2020, 7. https://www.smh.com.au/culture/art-and-design/artist-danila-vassilieff-was-selling-his-house-there-was-just-one-catch-20200731-p55hg3.html.

[2] See Felicity St John Moore, Vassilieff and His Art (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1982. This biography was the subject of two Supreme Court defamation cases brought by Elizabeth Vassilieff against the author commencing in 1982 and 1987. Both decisions were in Elizabeth’s favour. The biography was republished, with amendments, by Macmillan Art Publishing in 2013.

[3] He commanded a Cossack regiment in General Deniken’s counter- revolutionary White army in southern Russia; after capture, he escaped from a Bolshevik prison.

[4] National Archives of Australia (NAA): A6119, 2968 and 2969.

[5] Jane Sutton, ‘Life with Danila Vassilieff: New Perspectives from Elizabeth Wolf’s Archive’, Quadrant, No. 538, July-August 2017, 115. One folder in her papers contains details of, in her words, ‘Danila’s non-income and the kinds of payments I made for him (This tiny fraction of surviving receipts is Not Even ‘the tip of the iceberg’) e.g. in 1952-53, Danila had my cheque book filled with signed blanks, to spend during the 4 months I was away abroad.’ Elizabeth Wolf Vassilieff Papers, Heide Museum of Modern Art, Box 4, Part 1.

[6] Sutton, ‘Life with Danila Vassilieff’, 114.

[7] James Gleeson, interview with Elizabeth Vassilieff, 8, 15 November 1979 https://nga.gov.au/research/gleeson/pdf/vassilieff.pdf. And unlike her, Danila was not ‘adversely recorded’ by ASIO.

[8] Elizabeth herself spoke to one of the protest meetings: ‘“Peace” talk rowdy’, Herald, 12 September 1952, 3; ‘“Why Ban Us?” Peace Delegate Asks’, Argus, 13 September 1952, 3; Phillip Deery & Craig McLean, ‘“Behind Enemy Lines”: Menzies, Evatt and Passports for Peking’, The Round Table. The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs, Vol. XCII, No. 370, 2003, 407-422.

[9] Though which she was in close contact with writers such as David Martin, Judah Waten and John Morrison, and literary magazine editors Clem Christesen (Meanjin) and Stephen Murray-Smith (Overland).

[10] ‘Soviet people passionately desire peace’, Tribune, 18 March 1953, 6.

[11] Another, apparently, was with the artist, Joy Hester, one of the Heide Circle. In her unpublished ‘Soldier into Artist: Notes for a Biography of Danila Vassilieff’, written after his death, Elizabeth wrote that he was a ‘liar, slanderer & adulterer…NOBODY in the world but me knows of these skeletons’. Her papers are held by the Heide Museum of Modern Art and the University of Melbourne Archives [2012.0020].

[12] See also ‘Vassilieff book fine reading for the holidays’, Tribune, 9 December 1953, 6.

[13] Letter, 30 November 1953, in NAA: A6119, 2968, folio 57.

[14] ASIO report, 19 February 1953, NAA: A6119, 2969, folio 41. ASIO noted that between 6 March and 10 April 1953, she addressed ten separate meetings and that she ‘is being worked hard by the Peace Council since her return’. NAA: A6119, 2968, folio 32.

[15] Daily News, 18 February 1953, in NAA: A6119, 2968, folio 31. Five years later, in contrast, she confided to a friend (an ASIO informant) that she saw acts of ‘official brutality’ in China and ‘a lot she did not like’, but ‘has never mentioned this and it is clearly pressing on her conscience’. ‘Interview with [blank], 23 January 1958, NAA: A6119, 2969, folio 122.

[16] See ‘Peace meeting’, West Australian, 20 July 1954, 9. At another meeting, attended by only nine, the reporter noted she was ‘a very capable speaker’. ‘Protest Meeting’, Narrogin Observer, 23 July 1954, 1.

[17] Personal conversation with John McLaren, 18 August 2001. See his Writing in Hope and Fear: Literature as Politics in Postwar Australia(Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 20-1, 27-9.

[18] Hilary McPhee, Memoirs of a Young Bastard: the Diaries of Tim Burstall (Melbourne: Meigunyah Press, 2012), 12-13.

[19] This was evident in her Alternative to War: principles and policies of the Australian Peace Council (Melbourne: Australian Peace Council, 1954), based on a speech, ‘Geneva Must Succeed’, she gave on 13 May 1954.

[20] ASIO Report, 27 November 1953, NAA: A6119, 2968, folio 56.

[21] In 2017, one of his 1938 paintings sold for $50, 000. https://www.invaluable.com/auction-lot/danila-vassilieff-1897-1958-soap-box-derby-193-27-c-25c417fa4d#

[22] ASIO Report, 20 July 1954, NAA: A6119, 2968, folio 74.

[23] Overland, no. 18, 1960, 45; no. 26, 1962, 36.

[24] ASIO Report, 12 February 1965, NAA: A6119, 2968, folio 148.

[25] See R.R. Walker, ‘Pat Mackie’s Lady’, Nation, 17 April 1965.

[26] ASIO Report, ‘C.P. of A. Interest in Vietnam’, 23 May 1965, NAA: A6119, 2969, folio 182.

[27] See ‘Creative Work in Art Show’, Herald, 4 April 1949, 7; ‘Art Show Opens’, Herald, 3 April 1950, 3; ‘Artist-Wife Has Full Life, Age, 12 April 1950, 5. At a joint exhibition at the Nolan gallery in Canberra, historian Humphrey McQueen spoke on Melbourne modernists: Canberra Times, 30 April 1987, 12.

Very interesting, opens up a whole avenue of reading for me. Thanks Phillip.