By Jonathan Strauss*

In the 1980s, a large, diverse and vibrant nuclear disarmament movement arose in Australia. This paper uses findings from archival research and interviews conducted by the author over several years to show that strategy in the movement was contended and the movement’s debates and internal development had a substantial impact on its rise and decline. The views of movement activists about how to campaign for its demands, such as an end to uranium mining and, especially, for the closure of nuclear war-fighting bases in the country, differed greatly. The appearance of the Nuclear Disarmament Party highlighted divergent views that had arisen in the movement about how to relate to the Australian Labor Party. A potential for alternative political and social leadership underlay the insurgent movement’s arguments.

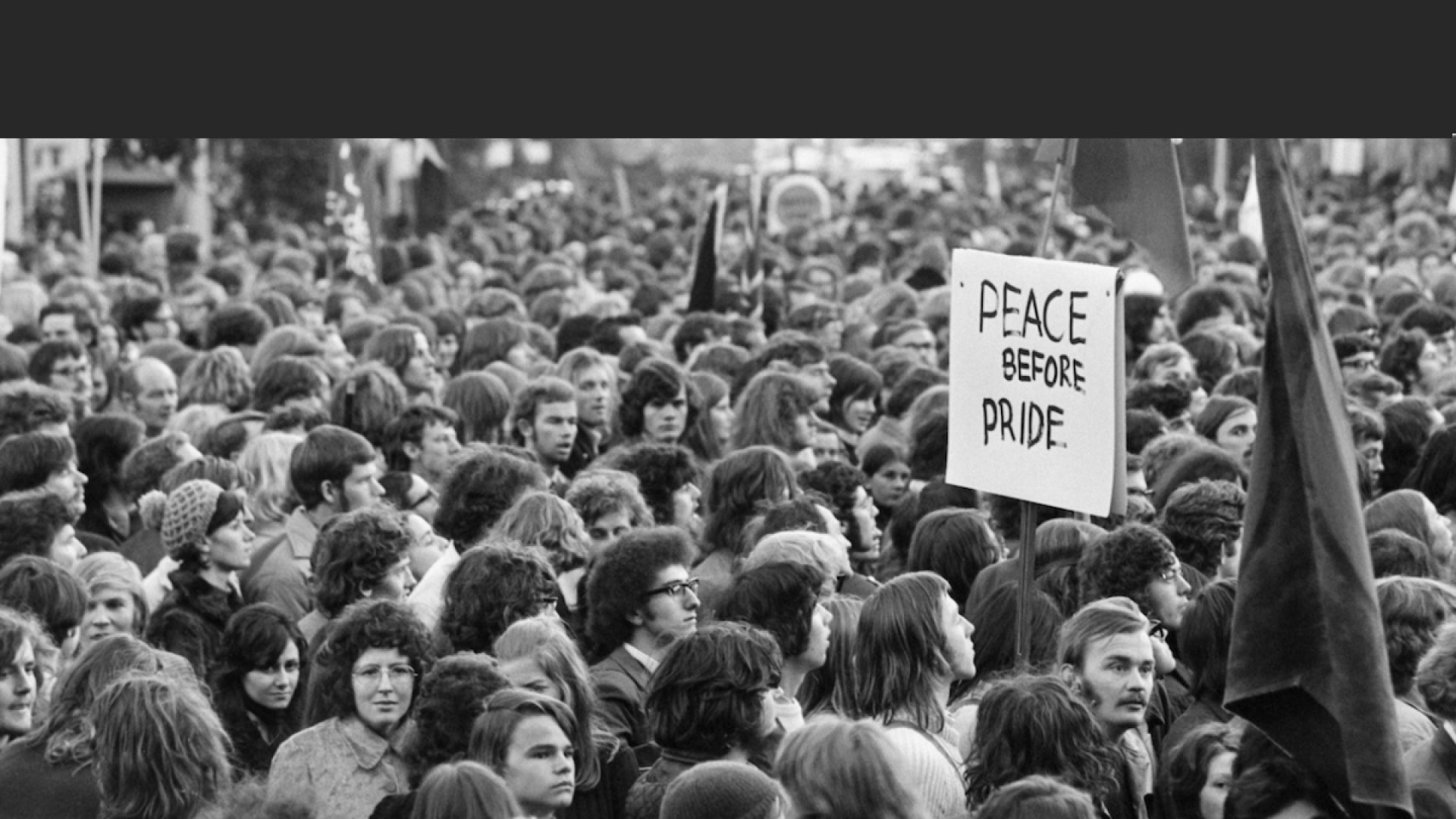

For the last four or so decades, the numbers of people that social movements in Australia have been able to mobilise in protest actions has tended to grow, although the movements have become less sustained and have not provided the same context for political radicalisation. In anti-war campaigns, this can be found in the journey from the Vietnam Moratoriums to the February 2003 marches against the second Gulf War. In between, in the 1980s, the Australian nuclear disarmament movement has been part of this. Its annual (March or April) Palm Sunday marches rallied in the nation’s biggest cities and many regional centres. These grew year by year, from an estimated 100,000 participants in 1982 to more than 300,000 in 1984 and 350,000 in 1985 – much larger than the Moratoriums – before beginning to decline, and then stopping altogether after 1990. As well, numerous and varied groups organised around or supported its campaign for nuclear disarmament, their actions only loosely coordinated beyond the local level.[1] At the movement’s height, the Nuclear Disarmament Party (NDP) was created, spurred by the movement’s inability not only to achieve its aim under either the Liberal government in the early 1980s, but also under the Labor government elected in 1983.[2] This marked the emergence of significant electoral opposition to the Australian Labor Party (ALP) to its left, with continuities to the Australian Greens. Yet the NDP was opposed by many – more likely, most – of the movement’s acknowledged leaders. This points to drivers of the insurgent movement’s dynamics, alongside the flow and ebb of the Cold War during the decade which is generally identified in discussion of the movement. The influence of those who sought opportunities for reforms through the ALP as part of the existing political system, emergent radicalism within the movement, and their conflict, played a key role in the movement’s development and decline.

The difficulties many encounter in analysing the 1980s nuclear disarmament movement in Australia largely flow from disregarding its interior development. Its emergence played down the campaign against uranium mining, contrary to the view of James Walter, and earlier Malcolm Saunders and Ralph Summy, that the movement re-emerged after 1977 combined with that campaign. Not only Walter, but Lawrence Wittner, suggested that opposition to US bases was a focus of the movement. However, in practice this demand was contentious within the movement.[3] Walter also confusingly identified the loss of the anti-uranium struggle in the ALP, “especially … the 1986 [ALP government’s] decision to sell uranium to France”, with a consequent shift in the focus of the movement’s protest to opposition to US bases. The impact of ALP policy in the movement was evident well before that decision.[4] Brendan Carins recognised this: according to him, attitudes to the ALP were sharply divided in the movement, sapping its dynamism, while the movement’s “rank and file” successfully combined their forces in the rise of the NDP. However, he argued that the movement’s potential to achieve change “was limited by its narrow middle-class support base”, which found a reflection in the dominant part of the movement’s leadership’s support for the ALP.[5] Yet he failed to acknowledge that he calle the movement’s base and the movement’s rank and file were the same, or to discuss any alternative leadership in the movement. Thus, he did not allow for the possibility posed by the insurgent social movement – the development of alternative social movement and political leadership (for him, the NDP aspired to pressure the ALP, which was the “only mass-based force for political change”[6]).

A feature of the 1980s nuclear disarmament movement in Australia was that it developed unevenly across the country. A key organisation, People for Nuclear Disarmament (PND) in Victoria, the structure of which consisted of individual memberships (for example, 1500 in 1985) and group affiliations, was founded in October 1981. Its formation broadened the movement’s leadership there: in particular, it involved independent socialist and other radical academics who came into the movement through a peace studies organisation. Among the larger movement organisations, PND was the first to call for the immediate closure of US bases in Australia. It also eventually adopted, in a close vote, a policy of opposition to Australia’s military alliance with the US. For several years PND did not affiliate to the Australian Coalition for Disarmament and Peace (ACDP), the movement’s national organisation, although PND took part in ACDP national consultations. Other statewide organisations eventually had similar structures and often took the People for Nuclear Disarmament name. But these came about in different ways: for example, NSW PND evolved out of the Assocation for International Cooperation and Development, a pre-existing peace organisation. Also, neither their breadth of leadership nor their discussion of aims appears to have progressed to the same extent. For these reasons, what happened in Victoria is a particular focus here.[7]

A revived movement

Australia has a long history of anti-militarism. From 1980, activists responded to overseas developments, such as the renewed arms race of the “second Cold War”[8] and the upsurge of opposition to that shown by large demonstrations in Western Europe and the US. They also wanted to end the Australian contribution to US nuclear war-fighting capabilities. A number of articles argued for a renewal of the nuclear disarmament movement.[9]

In Victoria, Joe (Joseph) Camillieri put the idea of a coalition of existing forces to closed meetings of three groups: Pax Christi, the Congress for International Co-operation and Disarmament (CICD) and the Victorian Association for Peace Studies. These decided to form PND and organise a public meeting in October 1981. Several church and women’s peace and anti-nuclear organisations were then invited to be PND founding organisations. The anti-uranium organisation, Movement Against Uranium Mining (MAUM), was excluded from this process: MAUM activists subsequently joined PND, but were bitter, and fearful that uranium issues had been downgraded in importance (indeed, anti-uranium demands, when maintained in the nuclear disarmament movement, were never most prominent, although in practice they remained an important political catalyst).[10]

There was no simple continuity between the anti-uranium mining movement that began in the 1970s and the 1980s nuclear disarmament movement. Among other things, the 1980s movement had a much greater capacity to mobilise. The Palm Sunday marches grew from about three or four times, to ten-fold or more, larger than previous efforts.[11] Behind that lay a mushrooming organisational effort. Alongside the long-standing peace organisations and anti-uranium groups such as MAUM and Friends of the Earth, unions, religious bodies, political organisations, international solidarity groups and other existing organisations affiliated to state anti-nuclear coalitions (for example, PND had 150 affiliated organisations in July 1983), and many new peace groups formed, such as:

- Occupational groups, most of which were professionally-based. The medical practitioners’ group was founded in 1981 and had more than 1000 members by the beginning of 1984. Lawyers’ peace groups formed in Sydney, Adelaide, Perth, Hobart and Canberra between 1984 and 1986. There were some employee groups, backed by unions, including one among metalworkers and another among public servants in the veterans’ affairs department.

- Women’s groups, which were typically informed by a radical feminism that opposed global violence, including violence against women.

- Student groups, first at some universities and then, beginning in 1983, among secondary students. By 1985 the latter had progressed to the point where a group in Canberra hosted a national conference, attended by two groups from both Sydney and Melbourne and one each from Adelaide and Perth.

- Local groups based on suburbs or regional towns. There were, for example, 12 of these in WA in the middle of 1984, and 75 in Victoria in 1985.

A 1985 list of peace groups named more than 350.[12]

The political orientation of the initial leadership of the nuclear disarmament movement was to support and influence the ALP, where the anti-uranium campaign had earlier succeeded in securing a policy opposing uranium mining. Indeed, many of those who had established profiles as peace and nuclear disarmament activists were ALP members and supporters, or members or supporters of smaller parties, such as the Communist Party of Australia (CPA), which had that orientation. A 1986 survey of people in the workforce found that more than two-thirds of respondents who belonged to nuclear disarmament groups stated they were ALP supporters.[13] At a 1985 public meeting, ALP Senator Bruce Childs spoke of “us, … custodians of the peace movement”. [14]

The ALP, however, had not only begun to reverse its uranium mining policy after 1982, allowing the operation of three mines, but also gave the nuclear disarmament movement few concessions. Once the party formed government, an Ambassador for Disarmament was appointed, but this appeared to have little consequence. The government also took part in the South Pacific Forum negotiations for a regional nuclear free zone treaty, but never questioned the entry of US nuclear-armed and nuclear-powered warships into Australian waters and ports. The New Zealand government, meanwhile, effectively banned these ships from 1984. Consultations between the government and peace groups only began in 1985.[15]

Childs’ speech acknowledged that the NDP had challenged the leadership of the ALP. Even before then, in 1984, more radically-minded networks of activists were emerging within the movement. PND’s existing leadership isolated them. Previously, individual members could vote at all PND general meetings, and local groups and other affiliates could send delegations of up to five or ten members. By 1983 these meetings were being held every couple of months or so, and 200 or more people were attending each one. Changes were put to the August 1984 annual general meeting: except for annual general meetings, individual PND members could not vote and affiliates’ delegations would be just two members. With the backing of many ALP and CPA supporters and the more politically conservative representatives of some local groups, these changes were adopted. Attendance at general meetings was immediately fell by half – and did not recover when members’ voting rights were restored a year later when a constitution was adopted. A CPA activist later observed that PND had steadily declined “since that dreadful AGM in 1984, when the vast majority of the grassroots activists were sent scurrying away and were, on the whole, lost to PND for ever”.[16]

Anti-bases campaigning

At this point, the PND leadership also returned to downplaying anti-bases campaigning, eventually leading to a division within the movement. Originally, PND had stated its main task was “removing … any facility or operation which contributes to preparation for nuclear war”,[17] but most of its planning and publicity for its first Palm Sunday rally raised general peace and nuclear disarmament concerns. It did not resolve that campaigning for withdrawal of foreign military bases had a central role for the movement until later in the year. Then, a discussion of anti-bases campaigning opened up in the PND Newsletter and in the organisation’s Executive. Anti-bases demands were also adopted for the following Palm Sunday marches. Yet the demonstrations featured slogans in 1983 and 1984 were “Disarmament Now: East and West” and “Disarm the Nuclear Powers” respectively. At this time, most anti-bases campaigners, backed by a large majority in PND, wanted to challenge the “pro-Soviet” parts of the movement. They supported a perspective of parallel unilateral nuclear disarmaments of each bloc, to be effected by independent peace movements. In the face of threats by some, like CICD, to disaffiliate, they also sought to placate those who initially opposed “anti-Soviet” positions, but the latter eventually supported these slogans because they were compatible with multilateral disarmament perspectives – unlike opposition to the bases.[18]

Anti-bases campaigners also began attempts to organise. At their initiative, the 1982 PND annual general meeting established a sub-committee to report on possible campaign strategies against the Omega submarine navigation base in Gippsland and rejected postponing mass demonstrations on this until the following year. The sub-committee moved immediately into organising demonstrations in Melbourne for October and at the base a month later: the latter would attempt to “occupy” the site. However, the PND executive supported only the Melbourne demonstration, and the sub-committee polarised in the debate on the occupation until the occupation’s supporters, primarily university students, were left isolated there.[19]

After the 1983 Palm Sunday march, PND adopted a program of action mainly because this had been proposed by Camilleri. This stated opposition to the bases would be a focal point of campaigns, but the demand it proposed to raise immediately was to stop the visits of nuclear powered or armed warships and planes. Also, its key campaign, a Disarmament Declaration, called for the bases both not to be expanded and to be removed. These contradictions reflected differences, and changing alliances, among the leading groups in PND. One of these included academics and movement workers such as Peter Christoff, Belinda Probert, Richard Tanter and John Wiseman. It emphasised the campaign against the bases, and in general considered the movement to be counterposed to, if also a pressure on, the government. Another group was associated with church-related organisations and the left of the ALP and had Camilleri as its leading representative. (For much of this period, until Camilleri’s resignation from the ALP in 1986, he was a member of the ALP Foreign Affairs Committee.) He argued that the anti-bases campaign was the “single most effective way” to work for nuclear disarmament, but because that campaign would not be easily won, the demands against warships and planes should be pushed immediately. A third group was organised primarily through CICD, which in a 1983 position called for a demand for the “non-expansion” of the bases. It appears to have followed the approach proposed by Phil Hind (who was one of the Communist Party members who would shortly leave to form the Socialist Forum group in the ALP), which was to campaign for intermediate positions, such as non-expansion of the bases, the removal of one base, or an inquiry into the bases directed at achieving a non-nuclear alliance, in order to gauge support. The combination of the first two had brought about PND’s position on the bases. But for the Declaration to be a national campaign, which Camilleri wanted, agreement was needed with groups interstate which had positions similar to CICD. In effect, these two groups came together through their common views that ALP policy was in some way “confused” about the alliance with the US and its bases – for example, that the party and the Hawke government had differences about this – or even that it had reservations about aspects of the alliance, such as the North West Cape submarine communication base.[20]

By August 1983, according to the activist Ken Mansell, mobilisation against the bases had become a side issue for PND. This perhaps overstated the case. PND was organising, as Camilleri had also proposed in April, a demonstration at the Watsonia army barracks in suburban Melbourne. The movement had now found out that this was the site of a satellite communications dish, operated by the Australian military’s Defence Signals Directorate, that transmitted submarine target location information to the US Navy. Up to 5000 people rallied there in October 1983 – the largest action that PND ever organised other than the Palm Sunday marches – in a precursor to further developments in anti-bases campaigning. Nonetheless, at this time women’s groups carried the weight nationally of public actions against the nuclear war fighting bases in Australia. They organised two peace camps, the first at the Pine Gap electronic surveillance base, near Alice Springs, in 1983, and the second at Cockburn Sound, a naval base in WA, in December 1984. According to Tanter, PND refused to give the Pine Gap camp financial support, because it “couldn’t be controlled by PND”.[21]

In 1984, however, the nuclear disarmament movement was insurgent and thus difficult for its existing leadership to control. The number of people taking part in the Palm Sunday marches soared, especially outside of Melbourne. A telegram from the foreign minister, which effectively claimed that the demonstrations supported the ALP government’s policies, was jeered, at least in Sydney. In Melbourne in June, a PND general meeting adopted action proposals including: a demonstration the following month outside the city’s ALP office, on the first day of the party’s national conference; a Hiroshima Day demonstration with the theme of oppositions to the US bases and alliance and to uranium mining; and a peace camp to be held at the Watsonia base before the end of the year. [22] The PND Council, which had replaced the Executive as PND’s elected leadership, refused to implement these proposals. In a circular it stated its support for some other activities – none of which were demonstrations, except the blockade of the Roxby Downs uranium mine in South Australia – and “reform of PND structures” (discussed above) on the basis that “we need to work together in the building of a broad coalition actively campaigning for nuclear disarmament”.[23]

The Watsonia Peace Camp Organising Collective, however, again won support for their action and recognition of it “as a means of launching” a more general anti-bases campaign at PND’s annual general meeting in August (many supporters of the Council had left this meeting after the Council’s proposed structural reforms were adopted and a new Council was elected).[24] Its publicity material highlighted the “first strike” capability of Watsonia and the US bases in Australia, calling them a “nuclear threat” rather than, as the movement had previously done, a nuclear target.[25] The camp, which included a number of rallies and theme days, ran over two weeks from October into early November. It involved both ongoing and new anti-bases activists, many of the latter coming from the Northcote PND local group, Young People for Nuclear Disarmament (YPND), and Socialist Workers Party members, who now “really did get involved in all phases” of an anti-nuclear action.[26] The peace camp’s effects should not be exaggerated: its largest rally was only up to 1500-strong. Nonetheless, its successes boosted the confidence of anti-bases activists, who increasingly saw themselves working outside the framework of PND: in Mansell’s view, this was “a turning point”.[27]

In the new year, Northcote PND activists won approval for a Pine Gap campaign group. Oddly, the key report to its first meeting, in May, was given by Phil Hind, whose anti-bases strategy was at variance with that of the Watsonia activists who formed the basis of this new campaign group. The group needed another meeting, a month later, before it adopted the demand to close Pine Gap, rather than renew its lease, when that expired in 1987: at the same time, it decided to support a YPND initiated action on the Friday evening following Hiroshima Day with this demand and to take that demand to the upcoming National Disarmament Conference. In July, PND Council decided to support an ostensibly radical (“Stop the City”) Hiroshima Day “protest against the arms race, unemployment and exploitation”.[28] Again, at the national conference, which began on 29 August 1985, the Pine Gap group distributed a paper that argued a Pine Gap campaign should initiate one against all the bases, which, because they were fundamentally for war-fighting, must be closed. The conference recommended, however, that the movement prioritise campaigning against renewal of the lease of the submarine communication base at NW Cape in 1988, rather than a campaign against a renewal of the Pine Gap lease in 1987.[29]

Campaigning about opposition to the bases had become a fault line in PND. PND’s organisation of the National Disarmament Conference was decisive in it moving closer to the ACDP. Although PND originally adopted “Close Pine Gap” as a theme for the 1986 Palm Sunday demonstration, planning and Council meetings added a new theme of “arms race / world poverty”, which became encapsulated in the sole slogan of the demonstration, “Disarm: Feed the World”. Meanwhile, the Pine Gap campaign group started to organise independently as the Anti-Bases Campaign. By the end of 1986, it helped to initiate the national Australian Anti-Bases Coalition, which became the major organiser of the campaign to rid Australia of the nuclear war-fighting bases. Its major successes were protests about Pine Gap in October 1987 and two years later against the Nurrangar base in South Australia. However, this coalition lacked the capacity for broad mobilisation that the previous form of the peace movement had.[30]

The Nuclear Disarmament Party

The other means by which the insurgent nuclear disarmament movement sharply posed the demand to close nuclear war-fighting bases was the Nuclear Disarmament Party (NDP). The party, officially founded in June 1984, adopted this as one of its three platform planks, together with stopping the passage of nuclear weapons through Australian waters or airspace and the mining and export of uranium. Many people involved in or supportive of the peace and nuclear disarmament movement felt that they had been betrayed by the ALP, which, besides its policy change on uranium mining, supported the Australian alliance with the United States that already involved, among other things, three US bases in Australia, US warship visits and the landing of US military aircraft at Australian bases.[31] The party’s founding figure, Michael Denborough, rejected both a request to join the ALP and the idea of standing as an independent candidate for the Senate. He favoured forming a new party in order to put these issues on the political agenda by taking votes away from the ALP. In the ranks of the movement, the NDP had strong support: the resources of many local groups were mobilised in the party’s campaign, and most of those most closely involved with the Watsonia camp were actively involved. Within six months the party established branches across the country, had 10,000 members and won more than 500, 000 votes – nearly seven per cent of the vote nationally – and one Senate seat when an election was held in December 1984.[32]

Much of the movement’s leadership, especially in its larger organisations, opposed or did not get involved in the NDP. Denborough explained the party’s formation was discussed and agreed to at “house meetings” in Canberra, but when he first sought further support, among movement supporters he knew in Perth, he “came back in disarray”. Then, at a meeting in Sydney, a week after the party was launched at a public meeting in Canberra, he said the project encountered “tremendous opposition” from established peace groups, the Democrats and proponents of a national green party, until:

A rather large peculiar friend we had stood up and said: “Well, we’ve had enough talk. Now, why don’t we just get on with it?” Something like that. And then three other people stood up and they agreed to do that. And so we then formed a NSW branch.[33]

This opposition persisted: former NDP candidate Peter Garrett was rejected as a speaker at the 1985 Palm Sunday rally in Sydney. He spoke, instead, in Adelaide. In Victoria, PND debated its own electoral intervention, but, in the end, nothing came of this. Among PND’s leaders, the group which were most interested in this, including Tanter, had initially rejected the NDP. They became invoved in the party’s election campaign, with Tanter becoming the campaign coordinator; however, once Garrett, a well-known musician, and the former ALP senator Jean Melzer, became NDP candidates, substantial impetus was added to the party. Other parts of PND’s leadership opposed the NDP: Camilleri, for example, accepted it was a positive development, but criticised its lack of alternative defence and foreign policies, organisation and failure to consult with peace movement organisations (although these were probably unable, because of their ALP and Democrats members, and clearly unlikely, to support the NDP).[34]

The NDP’s impact was not limited to an election campaign. It changed the terms of the debate on nuclear disarmament and uranium issues. For the first, and only, time, the Palm Sunday demonstration in Victoria would have no general slogan at all. PND debated three demands – no warships, no bases and no uranium mining – versus two, to the exclusion of opposition to uranium mining; three won. Before the demonstration, a demand was added to stop the testing of a new missile, the MX, in the Tasman Sea. However, the movement also immediately rose to act: not just the “usual suspects” for such protests – YPND held a 13-day vigil at the US Consulate – but PND itself organised a thousand-strong demonstration and the left of the ALP expressed its opposition. Before Palm Sunday, this demand was achieved when the re-elected ALP government’s support withdraw support for the tests; this became the only clear example of the enactment of a demand of the movement. Meanwhile, the party also began to organise large public meetings and to get involved in other forms of campaigning.[35]

Then, in April 1985, the NDP split. A majority of the active members of the party did not leave, so the party did not collapse; indeed, in the 1987 double dissolution election it again won a Senate seat, in NSW. But Garrett, its popular figurehead, and its Senator, Jo Vallentine, went, and with them gone its support declined and its membership fell even more quickly.

The division in the party was largely debated as organisational issues: one group or another supposedly favouring centralisation, in their own interest, in branches; proscription of members of other parties; membership decision-making by meetings or postal ballots; automatic appointment of former candidates to decision-making bodies; action by parliamentary members independent of the party; and, thus, generally control of decision-making.[36] Yet the culmination of differences that emerged among party members in the months after the election rather reflected their views about strategy for the NDP. The “fundamentally radical”[37] character of the party – Denborough, for example, believed the NDP “was a revolt against all the forces of darkness in general, and the inequalities between the rich and the poor”[38] – was not in dispute. Also, on either side some held that the party would tend to be incorporated into some broader politics, since such views were held on either side. What NDP members disagreed about was what to do about their party’s radical character and therefore what kind of party they wanted the NDP to be. The splitting group thought radical politics threatened the NDP. According to Vallentine, that would have marginalised the party and made it unsustainable. NDP members who supported the party as it had been constituted argued the party’s platform, and its sole political requirement for membership of support for that platform, brought it widespread support, including from disillusioned ALP members. According to them, a broader platform and stricter membership provisions would threaten that support and reflected the impact of pressure on the NDP to be “respectable”.[39]

Conclusion

The nuclear disarmament movement in the 1980s is suggestive of a link between the anti-Vietnam War movement and the movement against war in Iraq in 2002-2003. On the one hand, the broad capacity for social movement mobilisation rises; on the other hand, the ability of a social movement to persistently oppose the government of the day declines.

In the 1980s movement, which in contrast to the other two movements primarily faced the ALP in government, those who supported and sought opportunities for nuclear disarmament action through the ALP responded to the insurgent movement by isolating the movement’s more radical activists. Practical campaigning on some key movement demands was contentious: first with regard to uranium mining, and then in opposition to the nuclear war-fighting bases. As the threat to the opportunist leadership of the movement emerged, they in effect divided the movement, keeping the greater part of the movement under their direction, and then demobilised that. The social movement mobilisation that was left in the hands of the radical activists proved to be too limited to sustain the movement. All of this began to play out in 1984 and 1985, and the decline of movement started then, to a substantial extent even before the heat went out of the Cold War (after Mikhail Gorbachev became the Soviet Union’s leader) and certainly before the collapse of Communism in 1989-91.

The 1980s movement is distinguished, however, by the emergence from it of a party which won relatively broad electoral support – at a level, for politics to the left of the ALP, that was not surpassed until more than a quarter-century later, when an ALP government had again been elected. Some argue that the NDP hindered the development of a green party through competition,[40] or its experience “made environmentalists wary of … the problems of transforming a social movement into a vehicle for parliamentary politics”.[41] These arguments ignore the impact of the political differences among potential supporters of a green party nationally, which prevented this development in the middle of the 1980s. This included a decision not to try to form a green party at a Canberra meeting in July 1984, when the NDP’s impact was identified as a reason but was, in fact, unproven. Meanwhile, the Sydney Greens were founded in August 1984: that party’s registration of the Greens name was partly an optimistic response to the NDP and it supported the NDP.[42] Arguably the NDP’s successes also inspired the whole range of new party projects that came in the years that followed, including what has become the Australian Greens. The NDP in its first months stood as an example of what a new party could achieve; first of all it was an opportunity seized. If this opportunity was then squandered, this involved the same problem encountered in the 1980s nuclear disarmament movement as a whole: conflict between those who sought opportunities within the political system as it was, and those who thought they could and had to build political support anew for what they want.

Jonathan Strauss writes and occasionally teaches in politics and history in Cairns after completing his thesis on the Accord and the politics of workers in 2011 at James Cook University. His ongoing research concerns workers’ political consciousness, including the roles of social and labour movement participation, issues related to the formation of new worker parties and insights offered by Gramsci’s work.

Endnotes

* This paper is largely based on research conducted for two theses, supervised variously by Doug Hunt and Andrew Milner. My thanks to them for their assistance, and also to the interviewees. Archival research with regard to People for Nuclear Disarmament (PND) in Victoria was conducted in 1986. The papers referred to were then held in working files by the groups as cited: the Hawthorn People for Nuclear Disarmament (a local group affiiliated to PND) papers were maintained by the author, to which he added papers provided by Steve Wright. The author has not been able at this time to ascertain the archive details for these papers, except where these have remained in the author’s possession (as indicated), but the following holdings can be noted: Papers created by Ken Mansell, State Library of Victoria, Libraries Australia ID 13692499; Records of thePeople for Nuclear Disarmament, 1981-92, National Library of Australia MS Acc GB 1994/1406, Libraries Australia ID 13723392. The former is likely to hold the Anti-Bases Campaign documents, the latter PND records, and either might have papers that were held by Hawthorn People for Nuclear Disarmament.

[1] Lawrence S Wittner, “Nuclear Disarmament Activism in Asia and the Pacific, 1971-1996,” The Asia-Pacific Journal 25, no. 5.

[2] Jackie Bornstein and Margot Prior, “A History of ‘Psychologists for Peace’ in Australia” in Peace Psychology in Australia, ed. Diane Bretherton and Nikola Balvin (London: Springer, 2012), 74.

[3] Verity Burgmann referred to removal of the bases as “the most publicised objective of the anti-nuclear movement”, but this does not show that the removal of the bases was the movement’s focus: Verity Burgmann, Power and Protest: Movements for Change in Australian Society (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1993), 203.

[4] Malcolm Saunders and Ralph Summy, The Australian Peace Movement: A Short History (Canberra: Peace Research Centre, 1986), 45-46; James Walter, What Were they Thinking: The Politics of Ideas in Australia (Sydney: UNSW Press, 2010), pp. 276-77; Wittner, “Nuclear Disarmament Activism in Asia and the Pacific.”

[5] Brendan Carins, “Stop the Drop,” in Staining the Wattle: A People’s History of Australia since 1788, ed. Verity Burgmann and Jenny Lee (Melbourne: McPhee Gribble/Penguin, 1988), 244, 250-251.

[6] Dennis Altman, cited in ibid., 250.

[7] Peter Annear, “Prospects for the Peace Movement,” Direct Action, 18 September 1985, 11; Carins, “Stop the Drop,” 243, 245; Saunders and Summy, Australian Peace Movement, 49; Richard Tanter, interview with author, 1986.

[8] The second Cold War arose when the 1970s “détente” between the Soviet Union and the United States ended and was replaced by a higher degree of confrontation between them. It was typified by the foreign and military policies of the US presidency of Ronald Reagan. Prominent parts of those policies included discussion of “first strike” nuclear war options and persistence with a program to deploy land-based “medium range” (and short flight time) nuclear-armed rockets in Western Europe.

[9] Joseph Camilleri, interview with author, 1986; ———, “The Legacy of Hiroshima,” Pax Christi 5, no. 5 (September-October 1980); Jim Falk, “The Nuclear Bonds,” Australian Society 2, no. 11 (December 1983): 20, 23; Herb Feith, “Towards a New Peace Movement,” Pax Christi 5, no. 2 (March-April 1980); Alan Roberts, “Preparing to Fight a Nuclear War,” Arena, no. 57 (1981); Keith Suter, “Prospects for Peace,” Pax Christi 5, no. 5 (September-October 1980); Tanter, interview.

[10] Camilleri, interview; Ken Mansell, interview with author, 1986; Tanter, interview.

[11] These and subsequent quantitative estimates provided are based on the author’s protest events survey of all issues of the newspaper Direct Action from 1980 to 1990, supplemented by reference to some issues of Tribune from the same period. A description of the method used for this survey is provided in Jonathan Strauss, “The Accord and Working-Class Consciousness: The Politics of Workers under the Hawke and Keating Governments, 1983-1996” (PhD diss., James Cook University, 2011), 205-10, 354-56.

[12] John Andrews, “The Physicians Movement for the Prevention of Nuclear War,” Peace Studies, no. 3 (May 1984): 7; Michelle Braid and Philipa Rothfield, “Women’s Action for Peace,” Arena, no. 66 (1984); Carins, “Stop the Drop,” 245; Shirley Cass, “How I Turned my Nuclear Dread into Rational Fear,” Australian Society 2, no. 1 (February 1983): 30-31; Jan Everitt, “Peace Directory,” Peace Studies (April 1985): 16-19; Falk, “The Nuclear Bonds,” 24; Sonya Franks and Louise Denoon, “National Peace Party,” Direct Action, 5 June 1985, 26; Suellen Murray, “‘Make Pies Not War’: Protests by the Women’s Peace Movement of the mid-1980s,” Australian Historical Studies (2006), 81-94; Jean Nickels, “How to Start a Community Peace Group,” Peace Studies (June 1985): 22-23; n.a., “Disarming Lawyers,” Australian Society (June 1986): 7; ———, “Workplace Group Formed,” Direct Action, 24 August 1983, 15; People for Nuclear Disarmament, Annual General Meeting, 24 July 1983, Minutes, People for Nuclear Disarmament, Melbourne; ———, Annual General Meeting, 15 September 1985, Minutes, People for Nuclear Disarmament, Melbourne.

[13] Carins, “Stop the Drop,” 244-45; J.S. Western, et al, The Class Structure of Australia, 1986 [computer file], 1986, Australian Social Science Data Archive, The Australian National University, Canberra. The survey was made available through the Australian Social Science Data Archive by the original depositors. Those who carried out the original analysis and collection of the data bear no responsibility for the further analysis and interpretation herein.

[14] Brian Jones, “Labor Ranks Support NZ Nuclear Stand,” Direct Action, 20 February 1985, 2,

[15] Carins, “Stop the Drop,” 249-50; Timothy Doyle, Green Power: The Environment Movement in Australia (Sydney: UNSW Press, 2000), 160; Jim Green, “Australia’s Anti-nuclear Movement: A Short History,” Green Left Weekly, 26 August 1998, http://www.greenleft.org.au/node/16973.

[16] Sheril Berkovitch, “What’s Happening to PND? What’s Happening to the Peace Movement in Victoria? A Report on the Last Year,” Lines Newsletter, Special Pre-Conference Issue (September 1986): 21. Also: Sue Bull, interview with author, 1986; Camilleri, interview; Mansell, interview; People for Nuclear Disarmament, Annual General Meeting, 12 August 1984, Minutes, People for Nuclear Disarmament, Melbourne; Annual General Meeting, 15 September 1985, Minutes; Tanter, interview. Camilleri argued, however, that the effects of the AGM were “swept aside” by the subsequent course of event: Camilleri, interview.

[17] People for Nuclear Disarmament, “Statement of Aims,” PND Newsletter, no. 1 (December 1981).

[18] Camilleri, interview; Mansell, interview; People for Nuclear Disarmament, Rally and Festival Planning Meeting, 9/12/81, Minutes, 9 December 1981, People for Nuclear Disarmament, Melbourne; Andrew Milner, “From Russia with Love or You Only Live Once” (Melbourne: Hawthorn People for Nuclear Disarmament, 1982), 1; People for Nuclear Disarmament, April 4 Media Kit (Melbourne: People for Nuclear Disarmament, 1982); ———, “Nuclear Disarmament, the Only Alternative,” ed. People for Nuclear Disarmament (Melbourne, 1982); ———, Annual General Meeting, 4 July 1982, Minutes, People for Nuclear Disarmament, Melbourne; ———, “Disarmament Now: East and West “, ed. People for Nuclear Disarmament (Melbourne1983); ———, “Disarm the Nuclear Powers,” ed. People for Nuclear Disarmament (Melbourne1984); Tanter, interview.

[19] Ken Mansell, “Reflections on the Anti-Bases Campaign”, 1982, in author’s possession; Annual General Meeting, 4 July 1982, Minutes; People for Nuclear Disarmament, Executive Meeting, 22 September 1982, Minutes, People for Nuclear Disarmament, Melbourne.

[20] Australian Council for Disarmament and Peace, “Disarmament Declaration,” ed. Australian Council for Disarmament and Peace (Melbourne1983); Camilleri, interview; ———, The Australian Nuclear Disarmament Movement – A Strategy for the Next Twelve Months, 1983, in author’s possession; ———, “Labour’s Disarmament Policy,” Arena, no. 64: 43-44; People for Nuclear Disarmament, General Meeting, 30 April 1983, Minutes, People for Nuclear Disarmament, Melbourne; Tanter, interview; “ANZUS and World Peace,” Tribune, 23 June 1982.

[21] Bull, interview; Burgmann, Power and Protest, 204; Ken Mansell, “Notes from the Rearguard,” First Strike, no. 3 (August 1983); Murray, “Make Pies Not War.”; Tanter, interview.

[22] Peter Anderson, “Marches Mark Deepening Antiwar Sentiment,” Direct Action, 2 May 1984, 12; People for Nuclear Disarmament, General Meeting, 2 June 1984, Minutes, People for Nuclear Disarmament, Melbourne.

[23] People for Nuclear Disarmament Council, Letter, 26 June 1984, Hawthorn People for Nuclear Disarmament, Melbourne. Emphasis in original.

[24] Bull, interview; Annual General Meeting, 12 August 1984, Minutes.

[25] People for Nuclear Disarmament, “What’s at Watsonia,” ed. People for Nuclear Disarmament (Melbourne1984); Research Group of the Watsonia Peace Camp Organising Collective, “The Watsonia Network and Preparations for Nuclear War,” ed. Watsonia Peace Camp Organising Collective (Melbourne1984).

[26] Bull, interview.

[27] Mansell, interview.

[28] Bull, interview; Hiroshima Day Committee, “Hiroshima Never Again,” ed. Hiroshima Day Committee (Melbourne: Hiroshima Day Committee, 1985); People for Nuclear Disarmament, General Meeting, 24 February 1985, Minutes, People for Nuclear Disarmament, Melbourne; ———, Council Meeting, 10 July 1985, Minutes, People for Nuclear Disarmament, Melbourne; ———, “Hiroshima Day: Stop the City,” ed. People for Nuclear Disarmament (Melbourne: People for Nuclear Disarmament, 1985); Pine Gap Campaign, Minutes, 11 June 1985, Anti-Bases Campaign, Melbourne; ———, Minutes, 13 May 1985, Anti-Bases Campaign, Melbourne.

[29] Joseph Camilleri, “Charting a Course”, 1985, Hawthorn People for Nuclear Disarmament, Melbourne, 4-6; Carins, “Stop the Drop,” 252; Ken Mansell, “Nic Witte, and Margaret Allen, Pine Gap: On the Agenda”, Anti-Bases Campaign, Melbourne, 1985, 1, 5-7.

[30] Ian Cohen claims that Sydney’s “Peace Squadron revitalised the anti-nuclear movement in Australia, after the defeat at Roxby Downs” of a 1984 anti-uranium mining blockade: Ian Cohen, Green Fire (Sydney: Harper Collins, 1996), 148. But the peace movement’s largest actions followed the Roxby defeat, while the Peace Squadron at most played a role in Sydney like that played nationally by the anti-bases campaign.

[31] Compare with Tom Bramble and Rick Kuhn, who, in discussing the February 1985 defeat of the government’s plan to aid US missile testing off the Australian coast, claimed the testing was “in clear defiance of the Party’s anti-nuclear policy”: Tom Bramble and Rick Kuhn, Labor’s Conflict: Big Business, Workers and the Politics of Class (Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 121. Bramble and Kuhn also attributed that defeat to the ALP Left, with cross-factional support. In this, they at first fail to mention the NDP and its 1984 election campaigns, and when they do, they downplay the influence of the NDP by stating it “fell apart … quickly” after the elections: ibid., 121-22. In February 1985, the NDP had not split and was, in fact, still growing.

[32] Peter Annear, “The NDP Split: What Really Happened?,” Direct Action, 8 May 1985, 10; Bull, interview; Carins, “Stop the Drop,” 251-52; Peter Christoff, “The Nuclear Disarmament Party,” Arena, no. 70 (1985): 14; Mansell, interview; Jo Vallentine, “A Green Peace: Beyond Disarmament,” in Green Politics in Australia, ed. Drew Hutton (Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1987), 55-56; Patrick White, “In This World of Hypocrisy and Cynicism,” Arena, no. 68 (1984): 13; C. Wilcox, “The Most Important Issue,” The Newsletter, no. 1: 5.

[33] Michael Denborough, interview with author.

[34] Bull, interview; Camilleri, interview; Gillian Fisher, Half-Life: The NDP: Peace, Protest and Party Politics (Sydney: State Library of New South Wales Press, 1995), 5, 54; Tanter, interview.

[35] Denborough, interview; R. Eason, “The Peace Movement, the ALP and MX,” Flashpoint 2, no. 1 (April 1985): 6-7; Fisher, Half-Life, 52-54; Bill Mason, “Protests in several cities follow MX furore,” Direct Action, 20 February 1985, 19; Charles Parker, “Garrett: Nuclearism a Disease,” Direct Action, 20 March 1985, 19; People for Nuclear Disarmament, “Disarmament Rally,” ed. People for Nuclear Disarmament (Melbourne1985); ———, General Meeting, 18 November 1984, Minutes, People for Nuclear Disarmament, Melbourne.

[36] Annear, “The NDP Split: What Really Happened?,” 10; Ian Cameron, “The NDP: What Went Wrong”, May 1985, cited in Fisher, Half-Life; ibid., 34, 58-62, 68-71; Denborough, interview.

[37] Jo Vallentine, “The Greening of the Peace Movement in Australia,” National Outlook (September-October 1989): 9.

[38] Denborough, interview.

[39] Frances Collins, “We’re Going out and Getting Branches Established,” Direct Action, no. 521 (8 May): 14-15; Denborough, interview; Ramani De Silva, “NDP Prepares for the Future,” Direct Action, no. 515 (13 March): 9; Fisher, Half-Life, xii, 5-7, 10, 43, 85-86; Nuclear Disarmament Party National Constitution (June 1984), reprinted as Appendix A in ibid., p. 137; M. Hockings, C. Wilcox and M. Perrott, “What Next for the Nuclear Disarmament Party,” The Newsletter, no. 1 (May 1985): 17; James Norman, Bob Brown: Gentle Revolutionary (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2004), 164; Jim Percy, The ALP, the Nuclear Disarmament Party and the Elections (Sydney: Pathfinder Press (Australia), 1984), 24-25, 28; Sian Prior, “The Rise and Fall of the Nuclear Disarmament Party,” Social Alternatives 6, no. 4 (November 1987): 7; Marian Quigley, “The Rise and Fall(?) of the Nuclear Disarmament Party,” Current Affairs Bulletin 62, no. 11 (April 1986): 15; Vallentine, “The Greening of the Peace Movement,” 8-9.

[40] Timothy Doyle and Aynsley Kellow, Environmental Politics and Policy Making in Australia (Melbourne: Macmillan, 1995), 130; Fisher, Half-Life, 5-6.

[41] Elim Papadakis, Politics and the Environment (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1993), 180.

[42] Fisher, Half-Life, 5, 77-78; Tony Harris, “Regulating the Greens: Federal Electoral Laws and the Emergence of Green Parties in the 1980s and 1990s,” Labour History, no. 99 (November 2010): 72.

CITATION DETAILS

Jonathan Strauss, “The Australian Nuclear Disarmament Movement in the 1980s”, Proceedings of the 14th Biennial Labour History Conference, eds, Phillip Deery and Julie Kimber (Melbourne: Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, 2015), 39-50. Available for download via The Australian Nuclear Disarmament Movement LH Proceedings.