By Judith Smart

The following is the text of a lecture given by Judy Smart to the Brunswick Coburg Anti-conscription Commemoration Committee, 3 May 2016. It is reproduced here with the author’s permission.

When feminist historians, led by Carmel Shute in 1975, first started writing about the part played by women on the Australian home front during the Great War, they stressed the negative effects. As Shute wrote in ‘Heroines and Heroes: Sexual Mythology in Australia 1914–1918’, ‘The mythology engendered by the Great War affirmed the dichotomy of the sexes and re-established the enshrined inviolability of the traditional sexual stereotypes of man, “the warrior and creator of history”, and woman, the mother, the passive flesh at the mercy of fate (or rather, man)’. Women, Shute continued, were expected to fulfil the traditional role of ‘watching and waiting’ and to confine themselves to tasks that serviced the ‘real’ work done by the men. Since then, revisionist critiques have emphasised activism and positive outcomes of the war for women. Certainly the war did encourage participation by women in public life on a more extensive scale than at any previous time in the nation’s history. Not only did this involve patriotic fund-raising and comforts work, which was indeed largely undertaken by women, though mostly of the middle classes; it also included recruitment and extension of prewar moral reform campaigns focusing particularly on drink, prostitution and venereal disease. Furthermore, radical women engaged in pacifist and anticonscription activities as well as in street protests in support of striking husbands and sons. But the issue with which women of most classes were primarily concerned on a daily basis during the war years was the cost of living, and this gave rise not only to consumer organisation but also to food riots. Women thus gained substantial experience in organisation and management as well as in public speaking and demonstrations, and this stood them in good stead, for there was unprecedented growth in women’s organisations of all kinds in the wake of the war, and in the willingness of ordinary women to become involved.

Today I am focusing on radical protests and anti-war political activism. The former included street demonstrations and disruption of meetings that recalled tradition forms of protest while also signalling a transition to more modern forms. Among the traditional forms of protest of relevance here were food riots. The underlying popular consensus that legitimated periodic pre-industrial bread or food riots has been called ‘moral economy’ to distinguish it from the modern economic rationalism. Any significant outrage to the accepted notion of common weal, such as soaring prices, malpractices among dealers or middle men, shortages and consequent hunger, could justify direct action in redress. A riot, then, was the signal of malfunction, not an irrational and mindless act of violence. The rioters were most typically the respectable poor who aimed at a restitution of their normal condition, not at revolution or radical reform. The traditional food riot was very much a female protest. It was women who noticed the first pangs of hunger in their families and who had to deprive themselves, thieve, lie, prostitute their bodies and ultimately spill over into riot.

During the 19th century, other types of popular protest also emerged, focusing on new economic issues—enclosures and the machine-breaking of the Luddites, for example. And all included substantial numbers of women concerned to defend their homes and families. Working-class as well as some middle-class women also became involved in the 1840s Chartist movement for radical political reform and democratic representation. Later on it was as the wives and daughters of strikers that working-class women took to the streets too.

It is not surprising that many of these traditional forms of protest should have migrated to Australia along with the convicts, gold seekers and settlers. And nor is it surprising that the traditional forms of protest should have been preserved longer by women whose domestic roles focused attention on spending and consumption. Rather than making money, they were principally concerned, as ‘workmen’s wives’ and the providers of food, to spend it wisely. During World War I in Australia there are notable examples of protest by women that have many of the characteristics of traditional riots and disruptive tactics, both political and economic, before women’s political protest, like men’s, was finally channelled into the conventional and ordered, more permanent, political forms of party

Continuation of popular ideas about justice and moral economy underpinned women’s participation in two quite different but related protest movements during the Great War in Melbourne—one about a specifically political issue (conscription), the other about the cost of living, which included the nearest one can come to a modern food riot. Both saw a series of spontaneous outbreaks led by women and espousing a quite clearly identifiable notion of traditional moral rights. But, in both cases, it is important to note the transitional character of the protests for they were also linked, however informally, to the organised labour movement and tinged with the rhetoric of socialism. One example of the latter was the establishment by radical anti-war feminists of a commune in 1917 to assist wharf labourers who struck to prevent export of flour—a self-consciously socialist and feminist attempt at alternative political organisation.

Incidentally, we can also see non-labour attempts to bring about institutional change to redress rising prices of food, for the cost-of-living protest movement was also bound up with middle-class women’s efforts to form a mass women’s consumer organisation, which, after the war drew in some thousands of women from all classes.

I am dividing the rest of what I have to say tonight about women’s anti-war activism in Melbourne into 3 sections dealing with working-class women’s protest against conscription; cost-of-living activism and demonstrations; and the Guild Hall Commune set up by women to support striking wharf labourers in 1917.

- Conscription

One of the war’s earliest effects was on working-class living standards, as we shall see. And it was the women who bore the brunt of the struggle to feed their families. It was all the harder if the menfolk of the family had enlisted—and they would suffer much greater deprivation than their middle-class sisters if husbands or fathers were killed or incapacitated. These women were probably partly responsible for the declining enlistments in the armed forces by 1916. By then, the numbers of incapacitated returned soldiers and the lengthening casualty lists had overshadowed the earlier tendency to view war as alternative employment. Working-class wives and mothers were refusing to allow husbands and sons to enlist (my grandmother in Carlton). It is significant that, after the manpower census, when enlistment cards were sent out to ‘eligible’ men at the end of 1915, only 4200 out of 8000 in the working-class suburb of Richmond replied, and most refused.

Large numbers of working-class women were prepared to stand up against the war and against restrictions on their liberty if they believed their families or their class were under attack. Their cause was thus partly a maternal one, one based on the protection of the home and the belief that home and family were the core of national identity. It is likely many believed it was their role as citizens to vote accordingly, and we have to remember that, unlike women in most of the other belligerent nations, Australian women had the vote. It is not surprising then that much of the propaganda directed to them focused on their roles as mothers and nurturers. The powerful anit-war message of the American song performed by Women’s Peace Army leader Cecilia John ‘I didn’t raise my boy to be a soldier’ was symptomatic. So popular did it become that it was banned under the War Precautions Act. Meanwhile, pro-conscriptionist and pro-war women emphasised the sacrifice their enlisted sons were making to protect their own families as well as other women’s sons who had stayed at home. This emotive emphasis encouraged an emotive response.

Australia was the only belligerent nation to ask its citizens to vote in a plebiscite on whether conscription for overseas service should be introduced, and the period encompassing the two occasions on which nation-wide votes were taken (October 1916 and December 1917) was one of unprecedented political polarisation, bitterness and violence. The anti-conscriptionists won narrowly on both occasions but it was a Pyrrhic victory in terms of its long-term divisive effects on the nation and its weakening of the labour movement.

Conscription as an issue was argued out by most supporters and opponents on intellectual, ethical and rational grounds, in the terminology of the rights and liberties of the individual in relation to the needs and rights of the state. And that is the way most historians since then have also tended to look at it because they have relied on what was written and said. Thus it appears as if the issue was essentially one of conflicting political principles within the dominant discourse of liberalism and democracy. Certainly this is one important way of seeing it but it is not the only way, and it focuses solely on the articulate minority and especially on men. It is, I would suggest, a matter of doubt whether all the modern arguments about abstract concepts like liberty, honour, duty, freedom etc. were of major import in most working-class people’s (especially women’s) decisions how to vote.

Women conducted campaigns specifically directed towards their own sex. The Labor Women’s Anti-Conscription Committee, formed in September 1916, joined forces with other left-wing anti-war women to form the United Women’s No-Conscription Committee. Members came from the Labor Party as well as the Socialist Party and the Women’s Peace Army and Political Association. Among the organisers were Sara Lewis, Jean Daley, Elizabeth Wallace, Vida Goldstein and Bella Guerin (Lavender). Other well-known members included Adela Pankhurst, Jennie Baines, Muriel Heagney and Mary Killury. Members conducted house-to-house visits, organised the distribution of anti-conscription literature, arranged cottage meetings and rallies, spoke on platforms at the Yarra Bank, and addressed factory workers during their lunch hour. Open-air gatherings were held throughout the suburbs where possible. In the first week of October, separate meetings were held on the one night at the Socialist Hall and the Guild Hall, where women from the WPA and VSP shared the platform. The Socialist recorded that ‘the two halls were … packed to the doors’.

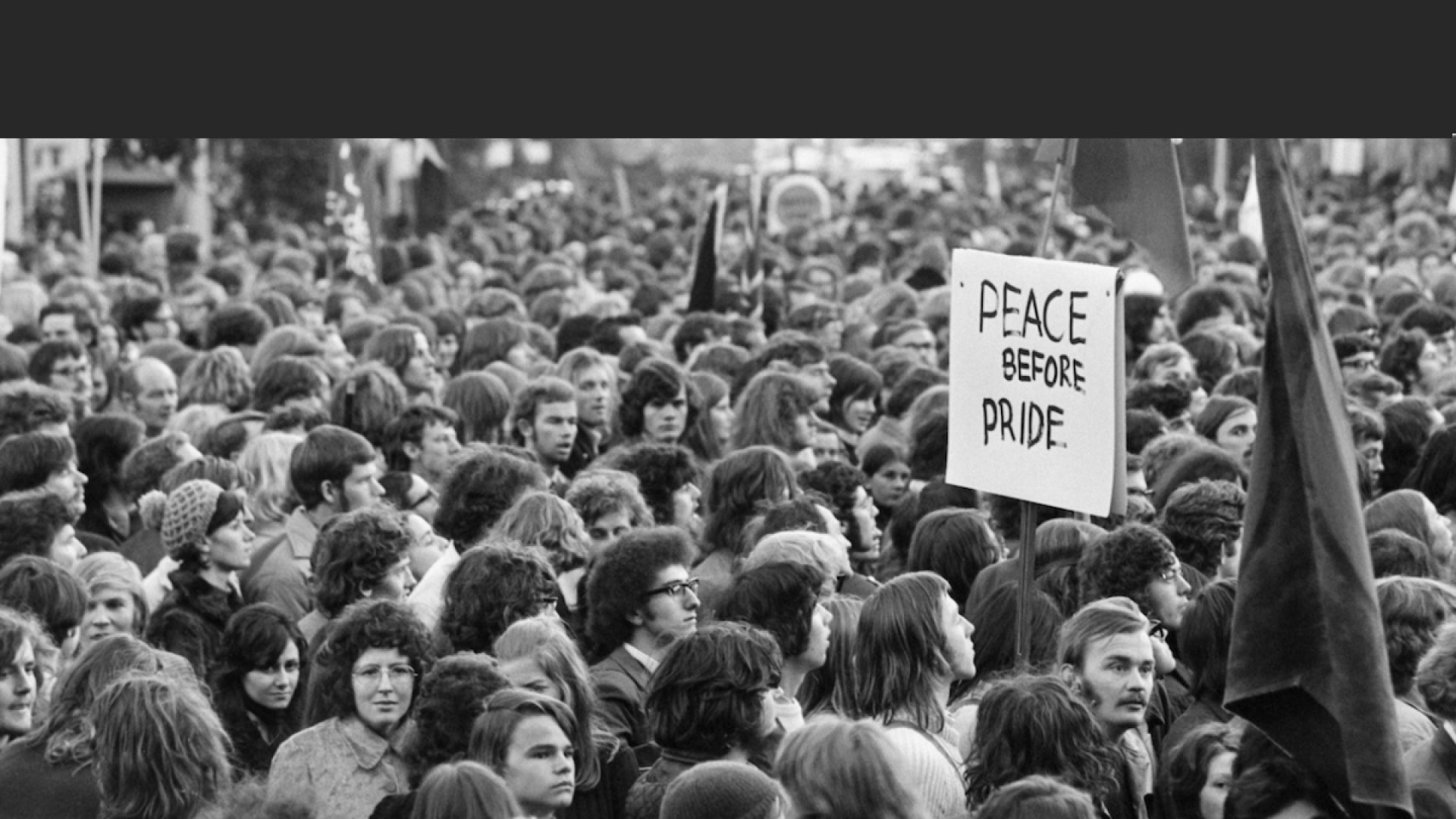

On 21 October 1916, a Women’s No Conscription Demonstration and Procession took place in the city, with 4–6000 women marching from the Guild Hall in Swanston Street to the Yarra Bank, where the crowd had swelled to 80,000. They were led by 8-year-old Madeleine Gardiner, dressed in white and carrying a wand topped with a feathered dove of peace. Behind her there were two young girls with a banner proclaiming ‘A Little Child Shall Lead Them’. Cecilia John followed on horseback dressed (like many others) in the purple, white and green colours of the English suffragette movement, which the Women’s Political Association had also adopted. The procession also included eight lorries with tableaux of various kinds and cars for the elderly or disabled. It did not proceed unchallenged but returned soldiers who tried to disrupt it and who attacked some of the women (one woman had a piece of a finger bitten off) were repelled by others and by unionists. According to Vida Goldstein’s biographer, it was the first time that Australian women had walked together in a peace procession. Sympathetic male activist F.J. Riley described the scene:

The women’s demonstration … was a gigantic success; in fact … we expected a procession, but we never expected to see the crowd of women who marched. The procession was over a mile long, extending from the Guild Hall right to the road that led to the Yarra Bank … During the afternoon, from about six platforms speeches were delivered, all of which were listened to attentively …

But there were other forms of demonstration during October too, and these were more spontaneous and came from the grassroots. In 1916, it was not just the principle of compulsion but also, at least as importantly, the way in which the public debate was conducted that emphasised other, more immediate meanings of freedom and raised them to a new level of intensity.

The operation of the censorship had made free expression against conscription difficult, but this was made even worse when state governments, local councils and other local authorities refused access to meeting places and halls under their control to the antis, a pattern that had been growing over some months. By the first week in October, availability of meeting places to anti-war and anti-conscriptionist activists in Melbourne was becoming extremely limited—the Melbourne City Council and most others refused the use of their halls, and street meetings in South Melbourne and other places were broken up. Arrests at such demonstrations—even where they were clearly disrupted by returned soldiers and conscriptionist rowdies—were confined almost entirely to antis.

The result was violent retaliation on the part of antis in the last three weeks of the campaign, and its purpose was quite specific—to give the pro-conscriptionists a taste of their own medicine. This seems to have been a spontaneous response from the grassroots and there is very little evidence of organisation or even encouragement from labour activists, socialists, IWW agitators or anyone else. Working-class people seemed to be saying to the conscriptionists, if you will not allow labour spokesmen and women, representatives of the working class, to speak to us in our own suburbs and streets, then we will not allow you to be heard. They decided to enforce their own form of justice (or moral economy) and proceeded to disrupt as many meetings as possible, using the count-out, stamping, prolonged jeering, chanting and booing, cock-crowing, interjection, invasion of the platform and loud renditions of popular songs.

The tactics were particularly favoured at women-only meetings, though they were not exclusive to them. The protests were rational and intentional acts on the part of most of the participants, though they were also similar to customary and traditional working-class crowd behaviour—those evident in pre-industrial carnival rituals and in entertainment activities from music hall to football. There was joy and a sense of fun in much of the protest activity, though this should not be seen to be in conflict with the serious purpose of the demonstrations, the assertion of power against the authority of the state. Carnival is symbolic revolution—it creates an upside-down world and flouts the rules of conventional order, it produces a sense of liberation but also empowerment—the reversal, if only on a small scale and temporarily, of the relations of power in their society (e.g. the gay and lesbian mardis gras in Sydney). During carnival-style protests in 1916, those with normally privileged access to public places were prevented from using them without challenge.

Women were especially noticeable in the anti-conscription activities I have described—localised demonstrations were the only ones accessible to them, and their suburbs and streets were in a very real sense, an extension of their homes, which they now felt to be invaded by hostile strangers. Their domestic duties and working experiences usually did not take them far from home and their horizons were consequently limited to a small geographical area. They were also less mobile than men. The direct expression of feeling and the outright disruption that characterised most of the meetings also suited greater involvement by women than the more formal debating procedures required in unions and Labor party meetings into which male worker discontent had largely been channelled. Ordinary working-class women had not yet been socialised into modern forms of polite and orderly protest. [AHS article, p. 210].

The Age reported one such occasion at a women’s demonstration organised by the pro-conscription National Referendum Council at the Fitzroy Town Hall on 10 October. It was described as ‘one of the most disorderly gatherings ever held in the suburb’. ‘Women, including a large number of mere girls’

trooped in early with noisy eagerness … It was asserted that many of those present came from other districts than Fitzroy … The platform was filled by ladies well known in Fitzroy. The arrival of Senator Lynch, with other speakers, was the signal for for a storm of boo-hoos and counter cheers which continued for some minutes.

The mayor appealed to the audience for a fair hearing for the speakers, but his voice was completely drowned by a pandemonium of shrill noises and stamping of feet. He was heard to announce Mrs. McInerny [president of the NCWV] as the first speaker, but, ungenerous to their own sex, the noisy mob howled her down.

Amidst the uproar Miss Lewis and Mrs. Morris, both well-known at the Trades Hall, vainly endeavoured to obtain for the speaker a hearing. “Although I differ from Mrs McInerny,” shouted Miss Lewis, “we should give her a hearing.” That was all she was able to utter above the din.

Mrs McInerny was not able to make herself heard and eventually sat down in defeat. Other speakers rose to address the doughty women of Fitzroy but were equally unable to make any impression on the noise levels. The mayor could do nothing except declare the meeting closed but the strains of the national anthem were lost in the shrieks and yells of triumph from the audience … The Age report continued:

Even then a large number of those present declined to leave. Some of the “antis” rushed the platform and endeavoured to form an opposition meeting. The lights were switched out, but even then the audience declined to go. The girls laughed and waltzed … and sang We Won’t Go Home Till Morning … The police, not caring to use force, found their task to clear the hall a most difficult one …

The Argus reported that ‘Young girls tried to swing the constables into dance with them’—an act consistent with good-humoured carnivalesque inverting of the relations of social order and authority.

Disruption of other meetings—some of them mixed, some women only—were reported at Richmond, Brunswick, Kensington, Williamstown, Prahran, Hawthorn, Footscray, Port Melbourne, Preston, South Melbourne and Fawkner.

Conscription as an issue was of specific relevance to working-class women since it directly affected their welfare and the survival of the family unit—it threatened to remove husband-breadwinners and sons. It thus contradicted their understanding of the rightful role of both local authorities and the state as the protectors of their welfare, of their bread and butter. It is not without significance that in a Kensington meeting, one woman intoned monotonously throughout the evening, ‘You tell me how a woman can live on 30 bob a week, and we will listen to you’.

Although the vote in 1916 was a narrow ‘yes’ in Victoria as a whole, the ‘noes’ had achieved an ever-so-slender majority in the Melbourne metropolitan area. While a good part of this achievement was attributable to the ingenuity, publicity and determination of the organised antis (including women), it was the support and spontaneous protests of a large number od anonymous men and especially women in the inner suburbs of Melbourne that enabled them finally to assert their right to be heard.

- Cost of Living Demonstrations

The same sort of concerns about welfare and the survival of the family were evident too in the food riots that took place in the months of August and September 1917—riots that resulted in considerable damage and destruction and inspired the authorities to step into quell them with the full force of the law. Before the war, some members of the umbrella National Council of Women had begun to take an interest in cost-of-living issues and the difficulties many working-class women had in making ends meet for a family on an unskilled worker’s wage. When the value of the pound declined 22.68 per cent in Melbourne in the first year of the war, the time seemed opportune. Between May 1914 and July 1915, meat doubled in price, bread rose 50 per cent and butter 62.5 per cent. The failure of the state government to impose effective price control stimulated the Liberal Party’s Ivy Brookes to call for united action among women on the cost of living.

Between May and July 1915, Brookes organised a Housewives Co-operative Association ‘to encourage co-operative buying and marketing of produce direct from the producer to the consumer’. The following months saw the establishment of bureaus in the ‘thickly populated’, ‘democratic’ suburbs where there were no local markets—so that producers could deliver foodstuffs directly to members at reasonable prices. But working-class women did not give the organisation the grassroots support it needed or rally to this call for consensus. This may be partly attributable to lack of cash to buy in bulk from the depots, but it also reflects growing class antagonism and suspicion of the leaders’ motives in light of their involvement in the recruitment campaign, their growing support for conscription, and their crusade against a planned referendum to increase Commonwealth powers over prices and monopolies. Vida Goldstein’s Women’s Political Association, though initially supportive, was quickly disillusioned, and labour movement women felt justified in their early suspicions. Raw class-based political conflict thus overwhelmed the tentative steps taken by middle-class women towards a gendered politics of consumption. By the end of 1916, a much-diminished Housewives Association had eschewed cooperative trading and converted itself into a propagandist group preaching the conservative panacea of thrift as patriotic sacrifice. But prices continued to rise unabated and labour movement leaders dismissed thrift as a ‘ploy of capitalism’.

By 1917 retail prices of food and groceries in Melbourne had risen 28.2 per cent overall. Wages had not kept pace; for Victoria as a whole they had increased only 15.4 per cent between 1914 and 1917. In addition, 1917 saw high levels of unemployment in Victoria, which, at 10.6 per cent, were the highest since the end of 1914, and rose even higher with the impact of the Great Strike in the months from August to October. The problem of food prices was complicated by a wartime agreement with Great Britain, whereby the wheat harvest for 1916–17 had been bought up by the Imperial authorities, and, from 1915, all frozen meat available for export was guaranteed to Britain. But a shortage of shipping in 1917 resulted in a build-up of frozen meat in Australian stores and left grain in railway sidings to the depredations of weevils and mice. Flour mills closed down and farmers stopped selling animals for slaughter, causing local unemployment in both industries as well as the closure of many retail outlets and hence shortages and higher prices for consumers. It was inexplicable to working-class families who were the sufferers that, as Adela Pankhurst put it, ‘while men were dying like flies in Europe for Australia, their children, their wives and their old parents are being robbed’.

On the afternoon of 15 August, for want of any action by state or federal governments, Pankhurst led a crowd of 2–3000 to the steps of Parliament House in Spring Street, in defiance of a War Precautions regulation prohibiting such gatherings passed only the previous evening. At this, as well as at an earlier meeting, the majority audience of women heard angry speeches against food exploiters and were urged to attack the cool stores and forcibly seize the meat. They were the first of many similar demonstrations and meetings that took place regularly well into September. The women were led and organised by the Women’s Peace League, a group formed specifically to raise support for the campaign to reduce the high cost of living but stemming mainly from the Victorian Socialist Party. These demonstrations about the cost of living in August–September 1917 seem to have similarities to the periodic and supposedly irrational outbursts about food prices and shortages in pre-industrial societies and in 1917, too, the protests were dominated by women, led but not always controlled by socialist organisers like Adela Pankhurst and Jennie Baines. For some weeks, there were almost daily demonstrations in the city of what the Socialist called ‘the people’s women’—they assembled outside Angliss meat works and butcher shops and other food outlets and factories and they were frequently dispersed by police after a few token arrests of the leaders. The pinnacle of the demonstrations was a ‘torchlight procession’ held on 19 September and attended by as many as 10,000 people at one point. Beginning at the Yarra Bank, the initial crowd of about 2,000 moved along the riverside to Princes Bridge, turned up Flinders St and continued to the top end of the city at Spring St, growing bolder all the while as thousands more joined in. Two women carrying the red flag at the head of the procession were quickly arrested and it was not long before the protest turned into a melée. Road metal picked up en route by the demonstrators was hurled at police and there were some minor injuries but, after an hour and a half, the crowd was broken up by baton-wielding constables, some sections breaking away and escaping down different streets into the city centre. £5000 worth of damage was done in a trail of rock throwing extending along Collins, Russell, Bourke and Elizabeth streets. Window smashing had taken place before and was to do so again the following Monday in Richmond. The Riot Act was eventually invoked and over 400 special constables were enrolled from citizen volunteers to bring order back to the streets. Adela Pankhurst was arrested on a number of occasions and eventually spent nearly 2 months of her 4-month sentence in Pentridge gaol before being released on petition by other women leaders on 18 January 1918. While in prison, and especially over the Christmas period, she was regularly serenaded by local women activists from the Coburg and Brunswick area who aimed to keep up her flagging spirits.

Working-class women had on the whole maintained traditional, community-based and local identities, in which networking and loyalty among neighbours and relatives, though necessary to survival, had no formal institutional existence. Their political activity in defence of the immediate economic interests of their families was ephemeral (short lived, for the moment)—a product of crisis and without means of maintaining continuous existence. It could be vociferous, powerful and focused but it took the form of direct action and carnivalesque symbolism rather than rational argument and ongoing organisation. In its methods and rationale, it displayed strong elements of resistance to middle-class efforts to turn working-class women into compliant rational and modern citizens. We see here considerable continuity in the concerns of working-class women and their means of protest with traditional food riots in pre-industrial societies. Such outbreaks occurred with greatest frequency when the system the people understood to be the natural order of things was in crisis and breaking down—as it was during the Great War. The preponderance of women in the crowds is also important in this context and indeed the police in Melbourne complained that their presence inhibited officers from using their batons effectively (!). Traditional communal and feminine values are evident in the fact that the demonstrators did look back to 1914 as ‘normal’ times, and their major target was indeed the profiteer, the middle-man, as well as the government, which had failed in its role of protector of the people’s livelihood. Adela Pankhurst also made it clear that she was operating on a pre-modern notion of natural and moral law that was not comprehended in the legalistic and free market assumptions of the Victorian and federal governments in 1917: ‘It appeared to me that laws which compelled [the people] to see their food destroyed by damp and vermin while their children were in want, did violate the conscience … We have a perfect right to break the law, if the law is not made in the interest of humanity’.

But despite these parallels, there were also differences in 1917 that demonstrate a modern class consciousness. For every reference to natural economic balance, one can also find a modern determination on the part of the leading protesters to bring about radical social and economic change. By the early 20th century in Australia, class conflict was generally more directed to industrial relations and improving wage levels than to household costs, and it was the unusual crisis of war time that forced primary attention again to prices. Socialist ideals infused the rhetoric and, whether the ordinary participants were class conscious or not, their awareness of class organisations like trade unions made their understanding of economic confrontation a different and more modern one. Thus their culture was no longer only one of organic rights and obligations, though these persisted among the women in particular; it was also one that included organised claims to political and economic power, including power for women (some police claimed that the leaders—Adela Pankhurst and Jennie Baines—had deliberately imported suffragette tactics into the demonstrations and this may well be true). Traditional concepts of a just price and a just wage had not disappeared but the rhetoric for political change made it clear that the purpose of popular protest was to challenge as much as to reassert the existing economic balance. For example, Pankhurst rallied her followers thus: ‘we will no longer allow the wealth to be in the hands of a few private individuals, we will no longer allow production to be carried on for profit’. The protesters worked alongside the unions and the Labor Party in their campaign against the high cost of living and shortages. They were also conscious of participating in a wider protest in support of the New South Wales strikers and their Victorian counterparts—in one of the afternoon street marches, the throng paused outside the Atheneum Hall where the National Service Bureau was enrolling strike breakers to wave umbrellas decorated with red ribbons and jeer at the scabs. They also sang socialist songs.

The Great Strike of 1917 was centred in NSW but had strong support in Victoria. The issue was over the introduction of a card scheme designed to record the exact time taken by each worker on each particular job. The unions interpreted it as the beginnings of ‘Taylorism’, the American scheme of ‘speeding up’ aimed at increasing productivity and profits but not necessarily wages, a means of squeezing more out of the workers in the same hours. The strike began in NSW on 2 August with 5780 repair and maintenance men walking off the job and persisted till 22 October, a total of 82 days. Approximately 76,000 workers went on strike in NSW, which represented about 14 per cent of the employees in the state’s workforce and 33 per cent of its total union membership. In Melbourne, by early September, 20,000 workers were affected—a third to a half of them actually on strike or locked out and the rest stood down or on short time. This formed the context for the last of my topics for this evening.

- The Guild Hall Commune

Mostly, the strikers’ wives and daughters, together with women of the labour movement as whole, were engaged in fundraising for relief of destitute families without a wage coming in rather than street protests. But, in Victoria, the Women’s Political Association quite self-consciously took a different approach, setting up a commune in the Guild Hall (now Story Hall) to help the wives and children of the striking wharf workers as well as the men themselves by providing the means of self help. The distribution of handouts would be replaced by assistance to strikers consistent in method and spirit with the fraternalist co-operativism long favoured in the organised labour movement. It can thus be seen as a means of erasing the taint of shame and humiliation that invariably accompanied resort to relief and its associations with charity, even when run by labour movement women. It is significant then that this new form of strike support occurred in a feminist organisation rather than among the women of the male-dominated Labor and Socialist parties where a largely subordinate and conventionally gender-defined role for women was assumed.

The Women’s Political Association and Peace Army did not officially support the street demonstrations about the cost of living and the violent methods used by Adela Pankhurst and Jennie Baines, though they opposed the harsh treatment of the demonstrators at the hands of the authorities and the refusal of the prime minister to hear their case. Instead the Women’s Political Association declared solidarity with the wharf labourers who first took decisive action on the cost-of-living issue on 29 July 1917 by resolving not to load foodstuffs for shipment overseas, except where they were for war purposes, ‘until the cost of commodities was reduced to pre-war rates’. Eventually in Victoria the cost-of-living issue merged with that of the time-card system that triggered the Great Strike. The NSW wharf labourers went out in sympathy with the railway workers who had downed tools on 2 August. The Victorian wharfies struck work in support of their Sydney comrades on 13 August, but the cost-of-living issue remained pre-eminent and they stayed out till November, well after other unionists in both NSW and Victoria had resumed work. For this reason the WPA regarded support for them as the special responsibility of women. They ‘did not strike for themselves, for better wages, better conditions. They struck for their class and for the community, against the increased cost of living, caused by gambling in food supplies. They struck for you and for me’.

In recognition of the sacrifices the wharfies had made in taking industrial action to reduce the cost of food, Vida Goldstein and Cecilia John set up a registration bureau specifically for the men of this union and their families, so that they could organise provision of food and medical assistance where necessary, especially for ‘nursing and expectant mothers’. The WPA also saw the wharf labourers’ action in sympathy with the NSW strikers as quite consistent with their action over the food crisis. Early in November, the Woman Voter printed the manifesto of the Unions’ Defence Committee in Sydney, which stressed that the strike in the railways over the card system had been a refusal by the men to submit to a scheme that ‘would have robbed them of every attribute of manliness, and reduced them to the wretched position of being half slaves, half machines’. To the WPA, then, both the wharfies’ rationales for strike action indicated a readiness on the part of the men to assert control over the quality of their life and work and to assist others to do so too.

The organisation of the commune was an evolutionary process rather than a preplanned blueprint but it resulted in a new system of mutual assistance and a conviction this could be the foundation stone of genuine social re-organisation. Cecilia John and other WPA members set about the task of supplying basic necessities. St Kilda and North Fitzroy PLC branches were acknowledged for ‘their very valuable help with funds and groceries’, as were ‘the willing helpers in the pantry and kitchen’, ‘those who have sent provisions, eggs, milk, vegetables and bread’ and ‘those who have helped with money’, which made possible the provision of meals for all strikers, their wives and children who came in to the hall. By early October nearly 1500 were being fed in the kitchen and restaurant on the premises and 5000 others supplied with groceries.

Although at first this was not very different from what the Socialist and Labor Party volunteers in the Women’s Relief Committee appointed by the TUDC were also doing for the other strikers and their families, the Guild Hall activities were increasingly directed to enabling the men and their families to be as self-sufficient as possible by encouraging the active participation of the wharf labourers themselves in setting up services and securing provisions. It was this that justified the designation ‘commune’. ‘Realising that men need some attention as well as the women and children’, for example, the WPA assisted two members of the Wharf Labourer’s Union with experience in cutting hair and shaving to set up a barber’s saloon at the back of the stage in the main hall. There were several men too who could repair boots, and Jennie Baines’s son, Wilfred, offered to train other members of the union, while husband George helped fit up the benches and ‘lent lasts and tools of every description’. On being asked about the importance the commune placed on these services, Cecilia John replied: ‘One of the first essentials for victory in the industrial fight is that the men shall keep their self-respect, and nothing tends to break a man’s spirit so much as being unkempt’. Vida Goldstein maintained that this was just as important as food, since the strike was about human dignity as much as economic issues. Throughout the whole period of the commune, union members themselves ran the various stores—second-hand clothing, grocery and baker’s shops, in addition to the two boot repair shops and the barber’s saloon—as well as the recreation hall and smoking room, and they also provided assistance to the women volunteers in the kitchens.

The commune did not become a permanent institution. It continued to operate till the following February but the Woman Voter announced on 22 November that the renewed threat of conscription necessitated the diversion of two thirds of the cash donations to the second campaign against compulsory military service. There was very little reference to the commune in the WPA journal after that until the issue of 18 April, which reported the annual meeting and gave an account of the activities of the ‘Guild Hall Commune Work’, which it dated from 6 August 1917 to February 1918. The round figures cited were impressive: 60,000 food parcels, 30,000 meals, 6500 haircuts, 30,000 items of clothing distributed, 2000 pairs of boot repaired, 200 cases of confinement or illness cared for, and £1500 in donations and almost 700 tons of food collected. And, during the Eight Hour Day march in March 1918, the wharfies made a diversion to the Guild Hall to salute the women of the WPA for their contribution to their survival during the long months of unemployment they and heir families had endured.

Conclusion

The actions of women during the war years did not generally challenge accepted gender roles—rather, the women accused the state of failing to protect and support them in carrying out these roles. Thus, if working-class women were politicised by their participation in the protests, it did nothing to stem the flow to organisations that vehemently rejected socialism in the years immediately following the war. The Women’s Peace League, which led the 1917 rioters, was purely ephemeral, the radical feminist Women’s Political Association and Peace Army both collapsed in 1919 and the Women’s Socialist League (VSP) splintered when the Communist Party was formed in the early 20s. The group that supplanted them as lobbyists for consumer justice was a revamped and re-energised Housewives’ Association, led largely by politically conservative women espousing a secularised Christian ethic who nevertheless took a strong feminist position on consumer issues in opposition to both capitalist and labour interests and used radical tactics like the boycott and cooperative marketing. The WPA was replaced by a more moderate post-suffrage feminist group—the Victorian Women Citizens’ Movement, the predecessor of the League of Women Voters of Victoria, which is still in existence today.

Judith Smart is a principal fellow at the University of Melbourne and an adjunct professor at RMIT University.

Judith Smart is a principal fellow at the University of Melbourne and an adjunct professor at RMIT University.

Thank you so much for this excellent article setting the scene of the anti-conscription referendums as well as the food riots of 1917.