By David Faber*

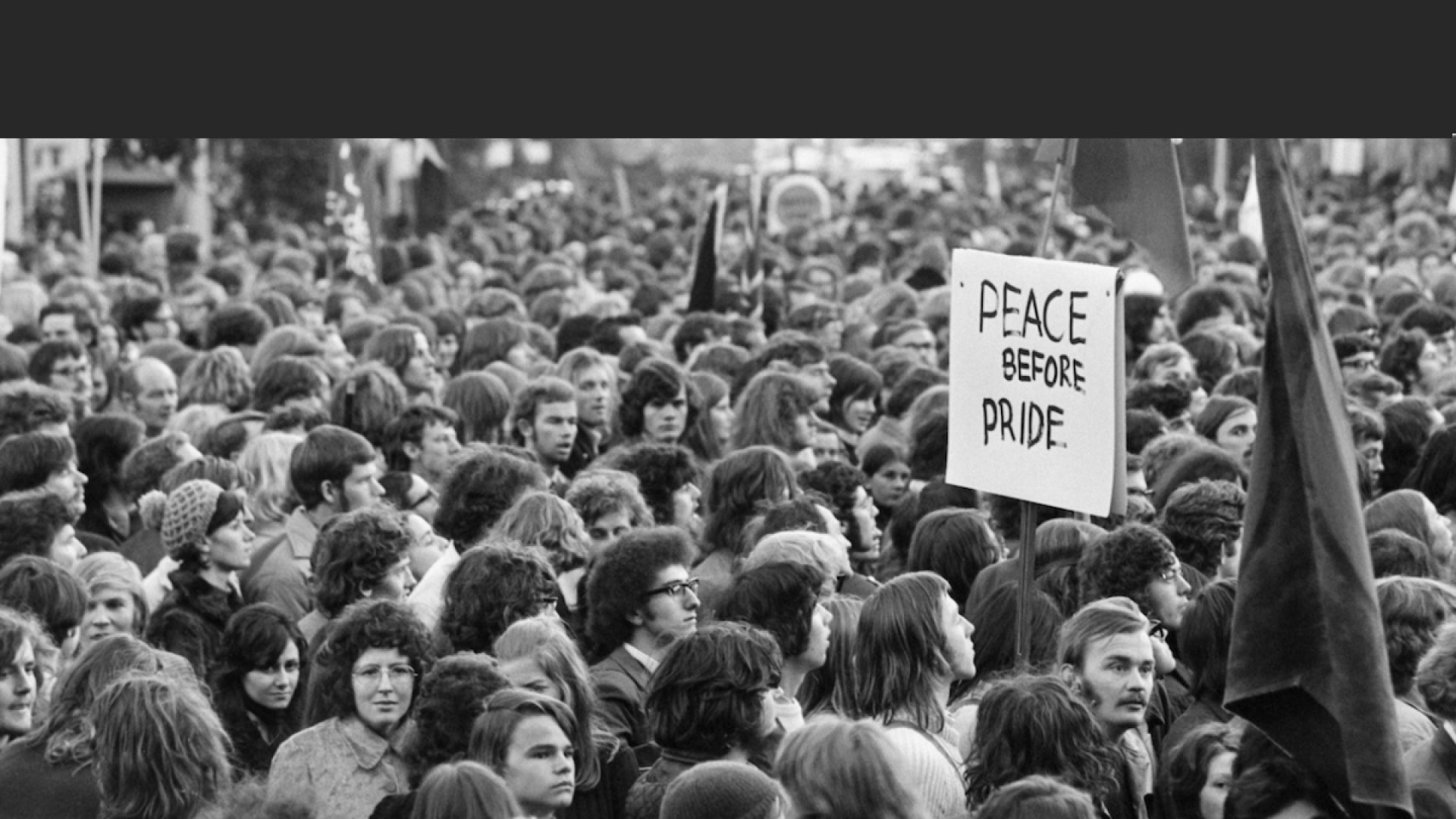

On 16 February 2003 as war clouds gathered over Iraq, some ten per cent of the metropolitan population of Adelaide from across the political spectrum gathered to protest the international lurch towards military conflict. This was the largest political demonstration in South Australian history, larger even than the historic Moratorium March against the war in Vietnam (though not of course more important). What follows is an historical account of how the antiwar movement of 2002-2003 was organised by the NoWar collective, and a discussion of its historical legacy from the personal perspective of a participant observer, the designated historian of the movement. The qualification “personal” is necessary because, no matter how seriously the historical obligation of objectivity is taken, each individual activist’s experience of the movement is different. Indeed no first person dimension of that historical moment could be captured otherwise. In addition, my recollections have been squared with those of over a dozen other activists, most of them prominent in one way or another.

It is first necessary to reconstruct the general climate of opinion within the NoWar collective. In 1996 the era of Labor Hawke and Keating governments came to an end and John Howard and the Liberals took power. The neo-liberal “reform” tendencies that animated these Labor administrations were redoubled with the change of office. The concerns of vested interests about perceived public and institutional “reform fatigue” became a thing of the past. In foreign policy the change of the guard signified little enough, as both major parties were committed to the US alliance, leaving disenfranchised critics to the left who favoured a more independent foreign policy in the tradition of Evatt and Whitlam. In his first administration, with the encouragement of the Murdoch press, Prime Minister Howard focussed primarily on domestic policy, oppressing the poor by introducing “mutual obligation” into welfare policy. He also aggressively took on the defensive power of the industrial flagship of the Maritime Union of Australia in the working class citadel of the waterfront, with mixed results. Even so Howard’s deft dog whistling of conservative concerns, particularly national unity and the ethnic composition of the country, had a way of morphing from an internal to an external policy focus as his “comfortable and relaxed” Australia became increasingly paranoid and jingoistic over the emerging refugee influx, especially after the criminal attacks of 11 September 2001 on US targets and the resulting declaration by the Bush administration of a “War on Terror”. Even prior to this Howard, a declared disciple of Menzies, had revived his deference to our great and powerful friends, America and Great Britain, insisting in 1999 that Australia had a role as deputy sheriff in our region. This did not go down well with our near neighbours. For these reasons by 2002 Howard was more than ever a bête noir for the left wing alternate constituency, which was the counterpart of his consecutive parliamentary majorities.[1]

By the time of President Bush’s notorious first State of the Union address on 29 January 2002, in which he lumped together as an “Axis of Evil” three admittedly notorious regimes that had nothing to do with Al-Qaeda, the US had already led a coalition including British and Australian forces against the Taliban in Afghanistan, which had refused to hand over or permit hot pursuit of Bin Laden. These developments had early attracted small protests in Adelaide, in which I had not participated, thinking on Hobbesian grounds that the US was probably entitled to respond militarily to the 9/11 provocation as an act of war. I later came around to the view of Gore Vidal that the outrage was best understood as a criminal act which required police intelligence rather than the blunt force of a full scale invasion. The eventual failure of the coalition to capture Bin Laden, who escaped to live clandestinely under the protection of the Pakistan intelligence service for a decade, confirms, I believe, the justice of this more acute approach.

Bush’s indiscriminate bellicosity alarmed me and millions of others. Indeed I always said Bush, Blair and Howard were the best recruiters the peace movement had ever had. It became painfully apparent that Bush and his neo-conservative and filo-Zionist advisers, like Paul Wolfowitz and Richard Perle, were obsessed with following up Bush senior’s unfinished business in Iraq. This was a regime with which U.S exponents like Donald Rumsfeld had been deeply complicit during the Ba`athist regime’s murderous war of attrition against fundamentalist revolutionary Iran. Imperialistic neo-conservative dreams of reorganising the Middle East at gunpoint to secure oil reserves and suit Zionist regional ambitions[2] were clearly opportunist. They had nothing to do with opposing terrorism and indeed would only lend it legitimacy. The supposed arsenal in Saddam Hussein’s hands of so called “Weapons of Mass Destruction” after his military assets had been bombed to perdition during Operation Desert Storm was incredible, had all the hallmarks of wanton self-delusion, and was not verified by Australian intelligence.[3] We in the peace movement mocked the whole dubious public relations exercise as being based on “Words of Mass Deception”.[4]

Nevertheless it needs to be remembered that many decent people were taken in at the time by this official propaganda with its bold and brazen pretence of accurate intelligence. I recall asking a medical specialist of my acquaintance, for whose intelligence I had the greatest respect, what she thought of the looming war, knowing her to be temperamentally pacifist with a profound distaste for violence and human slaughter. To my naïve surprise she said she thought it all depended on whether Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction. We were offering resistance to a formidable officialdom, whose views were being magnified by an uncritical mainstream media, so I really shouldn’t have been caught so off guard.

The roots of opposition to Washington’s designs went back to the Gulf War and beyond. I for example had first met political staffer and Middle East solidarity activist, Mike Khizam, on campus at Adelaide University in 1982, opposing apologists for the war crime of the Sabra and Chatila massacres in Beirut during Ariel Sharon’s invasion of Lebanon. Other activists like Stephen Darley were prominent organising the Palm Sunday peace rallies of the 1980s. I lent Mike a very modest hand in protesting the 1991 Gulf War and Prime Minister Hawke’s dispatch of Australian naval vessels to participate in it. This was when the first manifestation of NoWar was born, the brand originally conceived as an acronym for Network Organizing Against War And Racism (NOWAR).[5] This 20th century organisation, sometimes referred to short-hand as NOWAR I, bequeathed an historical legacy, some activists, a contact list and some funds to the successor 21st century organisation. Some NoWar activists in 2002-2003 were to be of Vietnam War vintage, including myself.[6] As the rhetoric ratcheted up during 2002, war psychology came to animate proponents and opponents alike. The looming conflict brought forth its own antagonists.

Mobilisation got under way on 17 September 2002 in a hired meeting room at the Pilgrim Uniting Church in Flinders Street, filled to capacity by well over thirty representatives of peace, human rights and social justice organisations from across the religious and secular divide, called together by the venerable Australian Peace Committee SA Inc. The Committee, led in Adelaide amongst others by veteran labour movement and peace activists Don Jarrett, Sue Gilbey, Irene Gale and the late Ron Gray, dated from the early Cold War on the national level.[7] Don’s labour movement activism had begun decades before in the communist Eureka Youth League.[8] Irene had begun her political activism even earlier at the age of six by holding a concert with her sisters to raise contributions for the fight of Republican democracy against fascism during the Spanish Civil War. Don had moved from the chair at the 2002 APC Annual General Meeting, which was addressed by an Islamic Women’s Association exponent, that a NoWar organisation be set up. Among those represented at Pilgrim Hall were the Catholic and Uniting Churches, the Medical Association for the Prevention of War, the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (celebrating its Great War centenary in 2015), Socialist Alliance and its youth wing Resistance, the reborn Communist Party of Australia (formerly the CPA splinter, the Socialist Party of Australia), unions, some university students and others. While many present were familiar with one another, others had never met before. In an effort to broaden the movement from the APC, Don nominated Mike to chair the meeting. Women’s movement exponent and social worker Jeanie Lucas became secretary and took minutes. These pivotal roles were to be later confirmed for the movement’s duration, involving a heavy commitment of overtime work. As discussion got under way, Jeanie declared that she wanted to see street marches as big and effective as the Vietnam Moratorium. Debate centred around alternative proposals to set up a writing group and organise a rally. From the chair Mike pointed out that the propositions being advanced in any case entailed expenses and recommended a hat be passed around. At this John McGill doffed his working man’s cap, collecting some $200 from those assembled. As the venue booking was about to expire, it was immediately resolved to continue elsewhere and accept the invitation of Greens Party secretary Anne McMenamin and decamp to the Party office in Wright Street. There a date of 5 October was set for the first rally, initiating a regular series.

Photographs taken at a subsequent rally on 30 November, which culminated at the Rotunda on the banks of the Torrens, feature the participation of Maugham Church Pastor Reverend Lee Levitt Olsson. Indeed the commitment of the Uniting Church throughout the movement is particularly warmly recalled by Jeanie and other key organisers. Another Christian church which participated was the historically pacifist Society of Friends, with Quaker Brian Arnott being an active participant in the NoWar organising collective. Brian’s politics was as progressive as anyone’s in the movement. His bona fides were accordingly never questioned by fellow activists, despite most of us being more or less atheist. The matter simply never arose in discussion amongst us. This raises the whole question of Christianity and indeed all religions and the left. At the 1997 Annual Conference of the Australian Society for the Study of Labour History Adelaide Branch, guest speaker Mick Atkinson MHA (now Speaker of the SA House of Assembly) complained that Christians were traditionally looked down on in the labour movement. In reply, thinking of the Palm Sunday peace mobilisation and that around the case of “turbulent priest” Father Brian Gore,[9] I demurred, claiming I had never known the religious question to be divisive on a left with traditions of addressing itself to all people of good will. Indeed as the late Douglas Jordan noted, “historically…Australian peace movements have characteristically been alliances between middle class activists, often intellectuals or Christian pacifists, and radical socialist or trade union groups”.[10] Certainly this was the case in NoWar. We always studiously avoided offending religious and even political sensibilities in addressing ourselves to the public, and sought involvement from all quarters.

I was attracted to one of these rallies in late 2002 and quickly gravitated to participation in the organising collective. Early on, I ran past Mike the proposition which I subsequently put to the collective that what we were doing, the way we were doing it and the public response we were getting was historic and ought to be recorded in process. Apart from my political identification with opposition to this war I had also been attracted to the movement by my interest as an historian in the theoretical challenges of doing current history as it happened. My offer to act in this fashion was accepted by the collective with stationary and photographic costs being paid out of petty cash. Artist Mij Tanith was commissioned to keep a photo-record of a number of the early demonstrations at this time. As the mad march to war gathered momentum our rallies became progressively larger than the norm for Adelaide for many years past, although I remember scripting one small rally called at short notice on Parliament House steps. I persuaded an anarchist acquaintance of mine from Queensland to read Jefferson’s preamble to the US Declaration of Independence to point out the vital importance of constructive autonomy in Australian foreign policy, just as the Viet Minh had done when they proclaimed the national independence of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam at Hanoi in August 1945.[11] I then read from Gore Vidal’s recent polemic Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace.[12] I prefaced the reading with the following remarks:

Gore Vidal, who describes himself as “a narrator of our imperial history” is among the most illustrious living American men of letters and public intellectuals. He says of himself “I think I’ve always had an up close view of the death struggle between the American republic, whose defender I am, and the American global empire, our old republic’s enemy.” Gore Vidal has been in love with the democratic ideals of the republic all his life, and has warned about its imperial sins for almost as long. In his writings he seeks to bring the USA with wit and insight back to its senses. If he is anti-American, then so is Mark Twain. We do not feel anti-American in his company. We contend that the belligerent policies of Bush, Blair, Howard, Rumsfeld, Cheney, Rice and Powell are not in the best interests neither of the United States, nor Britain nor Australia.

As a former schoolboy orator and debater, to be able to participate in this way was very gratifying. Mike Khizam watched over the proceedings and I was pleased and relieved when he told me he considered the rally a discrete success. I also wrote throughout 2003 a regular column against the war for the Adelaide University campus newspaper On dit, whose editors, one of whom was an anarchist, were supportive of the movement.

What was so characteristic and effective about the collective mode of organisation? Starting out at around 50 participants, it stabilised at around 80, although Socialist Alliance exponent Lesley Richmond remembers some 120 crowding the Greens Party office on one occasion. Leadership was widely diffused non-hierarchically, the sense of participation thereby generated retaining the enthusiasm of all contributors. Certainly despite their centrality Mike and Jeanie were never invested with the status of Beloved Leaders as per the old left tradition of the Cult of Personality. Nevertheless they were the two principal activists around whom the rest of us chose to revolve, shouldering the burden of unrelenting commitment to keep connected a collectivity which numbered personalities of disparate psychological, cultural and political backgrounds. Not that there weren’t personality clashes and moments of dissension. One day for example I was invited to chair the collective, and having a labour movement background addressed the assembled activists as “comrades”. A feminist zealot snarled at me “That’s sexist!” I had it on the tip of my tongue to point out to her that the term was in fact gender neutral, but thought better of it and ignored her the better to get on with business. On another occasion the same woman objected to me referring to “the Great War”, interjecting “How can a war be great?” This time I took her to task, pointing out that World War I was so referred to at the time because of its terrifying scale. It is instructive here to note that Jeanie early issued a warning on such matters at the NoWar meeting of 7 November 2002, under the heading “Harmony”.

Jeanie brought out into the open some problems in-group dynamics; group relationships; discord. Disparate ideologies and personalities exist, and this diversity must be accommodated for the sake of the cause: NoWar.[13]

But all things considered there was little enough interpersonal friction and sectarianism, personality clashes and political disenchantment. Some liked to think the Adelaide movement was particularly well behaved in this regard.

Most activists pulled together in the common cause most of the time, some in large ways, others in small. A few examples are in order here. Colin Mitchell displayed a literary knack, which amused and gratified not a few of us, for getting letters into the editorial columns of The Advertiser. Veteran of the socialist movement, Renfrey Clarke, gave sage advice. Don Jarrett, who was in due course designated chief marshal of the mega-demonstration of 16 February 2003, was very industrious in the collective’s organisational work, drawing particularly on his union links, and considers it a copy book example of how to organise politically in modern society. While I agree with him that the collective was politically successful in mobilising activists and public opinion to ensure that war when it came could not be waged in our name, I do so with some reservations, which I will come to later. All in all the collective mode was appropriate to the given historical moment of high and serious political excitement which obtained as the community addressed the question of war and peace, one of the most important any society can face. To the extent that revolution is not a matter of violence in the streets or the overthrow of constitutional states, but rather the conduct of qualitatively elevated politics on other than a routine business as usual basis, it is no exaggeration to say that we were successfully practising revolutionary politics, whilst being very far from being, as the Howard Government alleged, paid agitators. On the contrary we were all unpaid volunteers, and overworked at that.

The call for a weekend of global protest against the war on the weekend of 15-16 February 2003 had gone out from London and the challenge was picked up by the NoWar collective as soon as it was received. As the great day approached Mike and Jeanie received such a volume of enquiries they estimated some 20,000 might answer the call in Adelaide; sceptical police estimated some 15,000 might turn up. Early on NoWar had advertised rallies in the press, but desisted, finding the investment poor value for money given feedback that most attendees were learning of rallies by word of mouth or email. The issue of again advertising in an uncritical mainstream press many of us felt was complicit in war mongering arose again at this time, and once again the pragmatic decision was made to advertise. We also gained the benefit of free advertising, given the editorial decision of The Advertiser to encourage debate about the ethics of secondary school student participation in our rallies. But early on the Sunday morning as we gathered under Don’s stewardship at Wright Street we had no idea that the public transport system was straining to deliver unexpected numbers to the assembly point in Victoria Square. We stewards were all a little keyed up and apprehensive. Rounding the Supreme Court with the others carrying an armful of literature, I was relieved to see a goodly number already in the Square, and proceeded to take up my designated distribution point on the corner of Flinders Street. It wasn’t very long before people seemed to be coming from everywhere and all the literature was taken, and it was time to link back with other marshals in the heart of the throng. Time passed very quickly and then the head of the march set off. The police had asked us to keep a traffic lane open, but it proved impossible to contain the crowd as it spread right across King William Street. A steward assisting Don as chief marshal became anxious about this, to the point where Don felt it necessary to calm him down with the firm observation “Today we own the streets!” When the march turned into Grenfell Street on its way to Hindmarsh Square, I headed for our ultimate destination at Parliament House. I don’t recall exactly what the state of preparations was when I got there but it wasn’t long before the proscenium of the House’s steps was a riot of colourful flags and often witty placards and banners with people stretching along North Terrace as far as Pulteney Street.

As the time came to address the rally Mike received a phone request from The Advertiser for a crowd estimate. Perplexed he turned to another speaker waiting his turn, magistrate Brian Deegan, and asked him what he thought. Brian replied that he’d been part of a full house at the MCG and that this crowd, stretching as far as the eye could see, looked as big as 100,000, so this became our official estimate, which the press accepted. As it happened I was at the same time at the other end of the steps next to a police sergeant who was asked his assessment: he shrugged and offered the same estimate. Moments later Jeanie, who was always careful to remain behind at our rallies to clean up so that the movement could not be accused of littering, phoned through to Mike the report that the rear of the rally had not left Victoria Square. Mike reported this at Parliament House to the joyous acclaim of the crowd. Brian thinks in retrospect that his was probably a substantial underestimate.[14]

Mike continued to warm up with the crowd with a memorable short speech that directly spoke to the alienation and disenchantment typical of liberal democratic citizens:

If you’ve had times when you listen to the stupid things that George Bush has been saying or John Howard has said and you think to yourself “Am I the only one who can see they are crazy?”, look around you. We are not alone.[15]

He went on to report of the millions who had marched in London, Madrid and Barcelona. He requested the head of the march to move further down North Terrace towards the railway station, but those in the prime positions could not be persuaded to give them up. One young man climbed into a tree to get a better view but fell heavily right in front of me, injuring his coccyx. An ambulance had to be called and was forced to inch its way across the intersection towards him: he was the only casualty of the day. ABC broadcaster and mistress of ceremonies, Julia Lester, likewise made slow progress through the crowd, arriving only just in time to get proceedings underway. Another ABC broadcaster, Peter Goers, also addressed the throng:

You are the best people in South Australia. You are linked with the world, which wants peace. The right wing governments say we are paid agitators and peaceniks. All we are saying is give peace a chance. Resistance![16]

The crowd was perfectly peaceful, law-abiding, civil and well behaved. This was not only in keeping with the occasion but just as well, because if the crowd had wanted to loot the city no one could have stopped it, for the CBD was in a gridlock and neither police nor organisers could budge. There were drivers trapped in a parking station in Grenfell Street by the immobile marchers in the thoroughfare. Yet not a pane of glass was broken, and no-one came to blows with frustration; fellow feeling was the order of the day. Participant Dr Marie Longo remembered “the electricity in the air. The sense of community. The pride…[uniting] people [of] all ages, ethnicities, socio-economic status” and recalled how animated conversation was afterwards at the Exeter Hotel “not just about the war, but about life, love and the universe.”[17] There was no mistaking the almost carnival atmosphere of celebration of positive values which had been noted also at earlier rallies, not without some misgivings given the serious business in contemplation.[18]

Speaking of seriousness, the important set piece speeches given, which were only heard because of a reasonable public address system by those in front of Parliament House (those as near as Government House heard nothing), were set in train with a Kaurna Welcome to Country from Auntie Veronica Brody. She proclaimed “a very, very warm welcome to land from your indigenous brothers and sisters of South Australia, who walk with you in support for NoWar!” The crowd was very appreciative, with Julia commenting appositely “You know what attacking a culture means.” Peter Coombe then poignantly sang a cappella – the very pertinent Joni Mitchell Vietnam-era peace classic The Fiddle & the Drum. Then a children and adults’ concert scheduled for the following Saturday was announced featuring Humphrey B. Bear and singer-songwriter Abbey Cardwell. Julia gently emphasised that Peter, an active member of the organising collective on the arts advocacy side of things, would headline without being didactic, speaking of love to kids.[19]

Then Flinders University lecturer, Dr David Palmer, a dual United States-Australian citizen, was brought to the microphone he had graced to acclaim at previous rallies. To cheers he began:

This war in Iraq is not our war. Bring home now Australian defence personnel. Australia must work with U.N. weapons inspectors, not against them as the current U.S. government is doing. The game is up George! We are sick and tired of your lies and deception. We don’t believe dropping 4,000 bombs over forty-eight hours during Phase II of Shock and Awe, will liberate Iraqis. The embargo hasn’t removed the dictator Saddam Hussein. War will only increase his legend and kill tens of thousands. This is a war for oil, although the Three Amigos deny this…Iraq had the second largest proven oil reserves in the world.

David continued by quoting a recent Manchester Guardian interview with former Adelaidean Rupert Murdoch, to the effect that “Bush was behaving very morally, very correctly and will follow through. We can’t back down now. Bringing the price of oil down to $20.00 a barrel would be one of the war’s main benefits, the best outcome for the world economy, better than a tax cut.” Any Security Council endorsement of the wilful, self-appointed Coalition of the Willing would destroy confidence in the UN. The day before weapons inspector, Hans Blix, had reported that his team had found no weapons of mass destruction but only some empty chemical munitions which ought to have been declared and destroyed. There was, therefore, no excuse for this war, when as American weapons inspector, Scott Ritter, had demonstrated, isolation and containment of Saddam Hussein was all that was necessary. War and occupation would only replace dictatorship with a puppet regime like the Shah or Marcos or warlordism as in Afghanistan. It would not bring democracy or end terrorism. We were part of the biggest peace movement in history, as shown by massive polling against the war in Spain, Britain, Japan, Turkey, Egypt and elsewhere. War would destabilise the region. Millions of middle class working Americans who remembered the tragedy of the Vietnam War were opposed to Bush’s warmongering. One hundred Labor MPs at Westminster had rebelled against the war, and Blair’s career was over. We were not powerless, we must overcome our fears. People not politicians had the real power. The global peace movement was just the beginning. That John Howard had dismissed the will of the majority as having no impact upon him boded ill for democracy. What was needed was not war but law enforcement, including prosecution of the Bali bombers; Osama Bin Laden did not after all live in Baghdad. Nelson Mandela had called for Bush to be thrown out of office. David himself had written to long serving liberal Massachusetts Senator Edward Kennedy calling for Bush to be impeached. Howard should resign and call an election. [20]

Next to the microphone was famed author Mem Fox who gave a pithy and passionate address:

Just look at us! There are tens of thousands of us, maybe a hundred thousand, here in great numbers for one great purpose, to stop the slaughter in Iraq along with millions of U.S. citizens and many millions around the world. We don’t belong to the Coalition of the Willing, we belong to the Coalition of the Unwilling. We want only to stop this war. Saddam Hussein is a tyrant. But where did he get his chemical weapons?: Donald Rumsfeldt. The hypocrisy is sickening. The coalition of killers claims as few civilians as possible will be killed: but we must stand against this slaughter of the innocents. Don’t the Iraqis have human rights? Why ignore them to restore them? Why kill to prevent killing? War would only increase the hatred of the fundamentalist fanatics and increase terrorism a hundred fold…

After Mem wound up her speech to thunderous applause, Mike returned to the microphone to ram home some vital points. A witty New York protestor had carried a toothbrush placard demanding “Fight Plaque not Iraq”. We had better things to do than fight Third World countries presenting no threat to us. Despite a government fear campaign we had mounted the biggest demonstration in South Australian history, driven by common sense and decency lacking in our leaders. If the impending war went according to plan, however, unlike us its victims would not be able to turn off the TV. War was always a Pandora’s box, easier to start than to finish, sowing seeds of hatred between peoples. But whatever happened it would not be conducted in our name. Mike then introduced serving magistrate, Brian Deegan, father of Bali bombing victim and Sturt footballer Joshua Deegan.

Brian spoke from the heart about loss and in the implicit conviction that the Howard Government had exploited and betrayed the Bali bombing victims.[21] His legal training was evident in his emphasis on the rights and duties of a parent. An evocative close paraphrase[22] of his moving, essential remarks, by journalist Tracie McPherson, was published the following day in The Advertiser, which is worth quoting in full:

I have a right to love and protect my remaining three children and we should not overlook the fact that these values are shared worldwide. Why should so many Iraqi children be condemned to the same fate as my child and the others in Bali? Bin Laden has succeeded in doing what he set out to do and what we were trying to prevent – we are doing his evil work. I have lost my son as a result of an undeclared war. Our government has cynically depersonalised these people who hold many of the same values we hold so dear. Don’t the Iraqis love their children too?

Democrat exponent Ruth Russell also addressed the rally, declaring her intention to go to Iraq as a Human Shield. Collective member Edward Cranswick also went to Iraq on the same humanitarian mission.

The legacy of the rally and the NoWar movement was complex. Clearly the 16 February monster rally had been a great success. Activist resourcefulness had generated an imposing public response. But as most of the collective quietly expected war to break out anyway, there was no triumphalism amongst us, only sober determination to continue our opposition. A few activists were dismayed at the thought of our work being “wasted”. I remember being surprised at hearing one activist muse in this sense on the eve of the rally. I realised that I had never thought we were likely to stop the war. My objective had been to politically isolate the proponents of war, make them indulge their bellicosity on their own responsibility. But many thousands who attended the rally were probably less pragmatic and more idealistic in their participation, and their disappointment was a factor in reduced attendances at protests after “Operation Iraqi Freedom” was launched. Mike had boldly predicted on the basis of the Gulf War precedent that after Australian boots hit the ground in Iraq, activist commitment and public support would drop away as the government supported the troops for all it was worth. We of course proposed supporting them by bringing them speedily home. I was somewhat sceptical about Mike’s prediction, thinking it a bit drastic, but he proved to be substantially right. This raised the question of our next move. Should we pack up and go home having done our dash? Or should we persevere in the hope of evolving a sustainable anti-war organisation? The latter option was preferred, the question was how. This returns us in conclusion to the question deferred above of the limitations of the collective, which were most evident in the attempt to carry on after the rally.

It is a key element of the concept of a participant observer that he or she intervene to shape and develop the processes under observation. Unaware of this theoretical imperative at the time, I had nevertheless acted to gain a hearing as a constructive critic of the collective’s business management methods. At the NoWar organising meeting on 8 April 2003 I circulated a one page discussion paper with the wordy title An opportune minimum of accountable democratic structure: a proposal. Despite undiplomatically describing the collective as a dysfunctionally undifferentiated committee of all business, it was surprisingly accepted as a basis of re-organisation under the leadership of an executive steering committee. Unfortunately this process bogged down as a bored collective dwindled, legal advice to adopt and adapt a model constitution from the Associations Act[23] being rejected in favour of laboriously reinventing the wheel by developing one clause by clause. This debate degenerated into an ideological confrontation regarding “direct” versus “representative” democracy between Stephen Darley on the one hand and myself and Bruce Hannaford on the other. I ended up retiring to my studies and the ranks of the movement after the first NoWar Annual General Meeting later that year, having been nominated media officer by Brian Arnott and losing to incumbent Green exponent Anne McMenamin by one vote. The NoWar executive worthily transacted much peace business in the name of a declining activist membership base until it was wound up in 2008. It responsibly contributed, for example, to the cost of the clean up of the Opera House after impolitic Sydney activists had daubed it with the NoWar slogan. During commemoration of the tenth anniversary of the February 2003 rally it was clear that veteran activists would do it all again in like circumstances.

Dr David Faber is a labour historian and Executive Member of the Australian Society for the Study of Labour History Adelaide Branch. He is an Executive Member with Jeanie Lucas and Mike Khizam of the Australian Friends of Palestine Association SA.

Endnotes

[1] This reconstruction of the historical context of the events of 2002 and 2003 is buttressed by readings of M. Kingston, Not Happy John!: Defending Our Democracy (Melbourne, Penguin: 2004); R. Manne (ed), The Howard Years (Melbourne: Black Inc., 2004); D. Marr & M. Wilkinson, Dark Victory (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2003); and C. Aulich & R. Wettenhall (eds.), Howard’s Second & Third Governments: Australian Commonwealth Administration 1998-2004 (Sydney: UNSW Press, 2005); R. Manne “From Tampa to 9/11: Seventeen days that changed Australia” in M. Crotty & D. Roberts (eds.), Turning Points in Australian history (Sydney: UNSW Press, 2009); T. Windsor “Going to war the Howard way”, The Saturday Paper, 1 November 2014.

[2] See the English translation from the Hebrew by Israel Shahak of Israeli journalist Oded Yinon’s “A Strategy for Israel in the Nineteen Eighties” (Belmont, Mass.: Association of Arab-American University Graduates Inc., 1982). The essay was originally published in Kivunim (Directions) A Journal for Judaism & Zionism, No.14 February 1982. See also the collection of essays Neo-Conned Again (Vienna, Virginia: Light in the Darkness Publications, 2005).

[3] Margaret Swieringa, “Howard ignored official advice on Iraq’s weapons and chose war”, The Age, 12 April 2013. Swieringa was the public service secretary from 2002 to 2007 of the ASIO, ASIS and Defence Signals Directorate committee of the Commonwealth parliament. These Australian agencies took foreign intelligence into account in their assessments.

[4] See undated flyer entitled “WMDs…Words of Mass Deception”, which from internal evidence may have been issued as early as February 2003; in NoWar Archives in the State Library of South Australia. Personal contact details of individual activists have been with-held for privacy reasons, and remain in the designated custody of Jeanie Lucas.

[5] The acronym embodied the belief that official appetite for war in the Middle East was racist and Islamo-phobic. The fully capitalised acronym was eventually dropped in favour of the more readily understood NoWar slogan after public feedback that the earlier acronym was obscure, but this did not occur until after the success of the rally of 16 February 2003. Here the more accessible form is used throughout.

[6] At the age of eight, I wanted to march in the Moratorium procession in Burnie, Tasmania, exploiting the credibility of my Cub Scout uniform. My timorous father talked me out of it on the grounds that ASIO might take my photo and compromise my employment prospects.

[7] For the inauguration of the APC at the national level under the rubric of the Australian Peace Council, see Douglas Jordan, Conflict in the Unions: The Communist Party of Australia, Politics & the Trade Union Movement 1945-60 (Sydney: Resistance Books, 2013), 61-2.

[8] For an autobiographic profile of Don’s labour movement involvement see Movers & Shakers: Stories of activists who have made a difference in South Australia (Adelaide: SA Unions, 2007).

[9] For a contemporary historical record of the Gore case see A. McCoy Priests on Trial (Melbourne: Penguin, 1984).

[10] See Jordan, Conflict in the Unions, 62.

[11] B. Tuchman, The March of Folly; from Troy to Vietnam (London: Michael Joseph, 1984), 240.

[12] G. Vidal, Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace: How We Got To Be So Hated (New York: Thunder’s Monthly Press/Nation Books, 2002), previously published in Vanity Fair in December 2000 but written prior to the presidential election of 7 November. The title derives from the analysis of US foreign policy by American historian Charles A. Beard; see Vidal, 150.

[13] Minutes of NoWar Meeting, 7 November, NoWar Archives.

[14] Testimony of Jeanie Lucas, Mike Khizam and Brian Deegan, January 2013

[15] NoWar Adelaide Rally CD 1, NoWar Archives.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Email, Dr Marie Longo to David Faber, 11 April 2013.

[18] See reported critical comment from a participant at a previous rally regarding a “fair atmosphere”, minuted under the heading “Rally Debrief”, NoWar Organising Group Minutes, 5 December 2012, NoWar Archives.

[19] NoWar Adelaide Rally CD 1, NoWar Archives.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Testimony, Brian Deegan, January 2013.

[22] That the McPherson quotes were not exactly verbatim is clear from the NoWar recording of Brian’s speech; he spoke longer than The Advertiser report suggests. NoWar Rally CD 1, NoWar Archives.

[23] My recollection is that this excellent advice came from activist Bruce Hannaford and MHA Kris Hanna, both legally trained.

CITATION DETAILS

David Faber, “‘Today We Own the Streets’: The Adelaide NoWar Rally of 16 February 2003. A Participant Observer Memoir”, Proceedings of the 14th Biennial Labour History Conference, eds, Phillip Deery and Julie Kimber (Melbourne: Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, 2015), 83-92. Available for download via Today We Own the Streets LH Proceedings.